On October 19-20, 2025, Amazon Web Services (AWS) experienced a significant outage (AWS status) affecting its US-EAST-1 region in northern Virginia. The root cause was DNS resolution failures for DynamoDB’s API endpoints, which cascaded across AWS’s interconnected services, disrupting major platforms including Snapchat, McDonald’s, Disney+, Roblox, Coinbas, Reddit, and Amazon’s own services.

While investigating the outage, I discovered that Amazon doesn’t use its own AWS Route 53 service for amazon.com’s DNS.

Eating Your Own Dog Food

“Eating your own dog food” (or “dogfooding”) is a practice where a company uses its own products or services internally. The phrase originated in the 1980s in the technology industry, and it serves several important purposes:

- Quality assurance: Internal usage exposes bugs and usability issues before customers encounter them

- Credibility: Demonstrating confidence in your own products builds customer trust

- Employee understanding: Teams gain firsthand experience with what they’re building and selling

Many major technology companies have embraced dogfooding as a core principle. Atlassian uses Jira for all internal development, recently detailing how they dogfood new features like their Rovo Dev coding agent across all internal Jira sites. Slack deploys every new feature to an internal “Dogfood” tier first, where all Slack employees use it before external customers see it, helping catch problems early.

These companies understand that if their products aren’t good enough for their own use, they shouldn’t be selling them to customers. A company that uses its own products creates a positive feedback loop, making the products even better.

DNS Check follows this same principle. We monitor our own critical DNS records using our service, including dnscheck.co’s authoritative nameservers, MX records, and TXT records. When we add new features or make infrastructure changes, we experience the same monitoring alerts, notification workflows, and diagnostic tools that our customers use. This internal usage helps us identify potential improvements and ensures we’re building features that genuinely matter for DNS monitoring.

Amazon’s DNS Infrastructure Choice

Given the importance of dogfooding, it’s notable that Amazon doesn’t use Route 53 for its flagship domain. Route 53 is AWS’s managed DNS service, marketed for its scalability, reliability, and global infrastructure. Yet amazon.com relies on third-party DNS infrastructure from Vercara (formerly Neustar’s UltraDNS).

The decision predates the launch of Route 53 in December 2010. Amazon was already using UltraDNS for amazon.com in 2009, when a DDoS attack on UltraDNS briefly took down amazon.com. Migrating a domain as critical as amazon.com to a new DNS provider carries significant risk, even when that provider is your own service. However, this choice means Amazon doesn’t directly experience Route 53’s operational characteristics for its most critical domain.

The October 19-20 outage adds an interesting dimension to this situation. AWS experienced a significant disruption due to DNS failures affecting its internal infrastructure, but its most public-facing domain operates on a different DNS provider’s infrastructure. Had Amazon been using Route 53 for amazon.com, it would have had more firsthand operational experience with Route 53’s behavior in similar public-facing scenarios.

Steps to Reproduce

To verify that Amazon uses third-party DNS infrastructure instead of its own Route 53 service, you can follow these steps using standard command-line tools.

Note for Windows users: The examples below use dig and whois (common on

Linux/macOS). On Windows, you can use nslookup instead of dig (nslookup

examples are provided alongside dig). Windows does not include whois by

default. You can use an online tool like who.is or

whois.com for IP address lookups.

1. Check amazon.com’s authoritative nameservers

First, query the authoritative nameservers for amazon.com:

$ dig amazon.com NS +short

ns2.amzndns.org.

ns1.amzndns.net.

ns2.amzndns.com.

ns2.amzndns.co.uk.

ns1.amzndns.co.uk.

ns1.amzndns.com.

ns1.amzndns.org.

ns2.amzndns.net.

Or on Windows using nslookup:

> nslookup -type=NS amazon.com

Notice the naming pattern: *.amzndns.* - these are not Route 53 nameservers.

2. Compare with Route 53 nameserver patterns

For comparison, check the nameservers for aws.com, which uses Route 53:

$ dig aws.com NS +short

ns-2028.awsdns-61.co.uk.

ns-1500.awsdns-59.org.

ns-164.awsdns-20.com.

ns-917.awsdns-50.net.

Or on Windows:

> nslookup -type=NS aws.com

Route 53 nameservers follow the pattern ns-[number].awsdns-[number].[tld]

where the TLD is typically .com, .net, .org, or .co.uk. This is the standard

naming convention for all Route 53 public hosted zones.

Note that aws.amazon.com uses a mix of nameservers, including some Route 53 servers alongside AWS-internal infrastructure:

$ dig aws.amazon.com NS +short

tp.8e49140c2-frontier.amazon.com.

dr49lng3n1n2s.cloudfront.net.

ns-1860.awsdns-40.co.uk.

ns-106.awsdns-13.com.

ns-905.awsdns-49.net.

ns-1402.awsdns-47.org.

Or on Windows:

> nslookup -type=NS aws.amazon.com

The presence of awsdns.* nameservers confirms that aws.amazon.com uses Route 53.

3. Identify who owns the amzndns nameservers

Look up the IP address of one of amazon.com’s nameservers:

$ dig ns1.amzndns.com A +short

156.154.64.10

Or on Windows:

> nslookup ns1.amzndns.com

Check the ownership of this IP address using whois:

$ whois 156.154.64.10 | grep -E "^(NetRange|OrgName|Organization):"

NetRange: 156.154.60.0 - 156.154.80.255

OrgName: Vercara, LLC

The IP addresses for all amzndns nameservers fall within the 156.154.60.0 - 156.154.80.255 range owned by Vercara, LLC (formerly Neustar). Vercara operates the UltraDNS managed DNS service.

Note: The grep patterns shown are compatible with ARIN (American Registry for Internet Numbers) output format. WHOIS output may vary slightly between different regional registries, but the ownership information will be present.

You can verify additional nameservers follow the same pattern:

$ dig ns2.amzndns.net A +short

156.154.69.10

$ dig ns1.amzndns.org A +short

156.154.66.10

$ whois 156.154.69.10 | grep -E "^(NetRange|OrgName):"

NetRange: 156.154.60.0 - 156.154.80.255

OrgName: Vercara, LLC

Or on Windows:

> nslookup ns2.amzndns.net

> nslookup ns1.amzndns.org

4. Confirm Route 53 nameserver ownership

For comparison, verify that Amazon owns the Route 53 nameservers:

$ dig ns-106.awsdns-13.com A +short

205.251.192.106

$ whois 205.251.192.106 | grep -E "^(NetRange|OrgName):"

NetRange: 205.251.192.0 - 205.251.255.255

OrgName: Amazon.com, Inc.

Or on Windows:

> nslookup ns-106.awsdns-13.com

5. Verify nameserver software identification

As a final confirmation, you can query the nameservers directly to identify their DNS software using a CHAOS class query:

$ dig +short CHAOS TXT version.bind @156.154.64.10

"UltraDNS Nameserver"

Or on Windows:

> nslookup -class=CHAOS -type=TXT version.bind 156.154.64.10

The UltraDNS nameserver explicitly identifies itself as “UltraDNS Nameserver”. Route 53 nameservers typically don’t respond to these CHAOS queries (they time out), which is a security practice to avoid revealing implementation details.

Summary

The evidence shows that:

- amazon.com uses nameservers (amzndns.*) hosted by Vercara, LLC (UltraDNS)

- aws.com and aws.amazon.com use nameservers (awsdns.*) hosted by Amazon.com, Inc. (Route 53)

Why This Matters

Amazon’s choice to use UltraDNS instead of Route 53 for amazon.com doesn’t necessarily indicate a problem with Route 53. Large enterprises often maintain DNS infrastructure decisions made years before newer solutions existed, and the risk of migrating critical domains can outweigh potential benefits. UltraDNS is a well-regarded DNS provider with a strong track record.

However, the lack of dogfooding does mean Amazon misses opportunities that come from using its own service for its most critical domain:

-

Operational experience: Running amazon.com on Route 53 would give Amazon direct insight into Route 53’s behavior under the same traffic patterns and reliability requirements it demands for its primary domain. This real-world testing would complement its existing internal usage and customer feedback.

-

Incident response: During DNS-related outages like the October 19-20 incident, having its primary domain on the same DNS infrastructure would provide additional operational data and motivation to resolve issues quickly. Teams would experience the same pain points as customers.

-

Customer confidence: When AWS sells Route 53 to enterprises for their mission-critical domains, those customers might reasonably wonder why Amazon doesn’t use it for amazon.com. Dogfooding sends a strong signal about a product’s readiness for production use.

-

Feature validation: New Route 53 features and performance improvements would be validated against one of the world’s highest-traffic domains, ensuring they work at scale before customers deploy them.

The October 19-20 outage highlighted how DNS failures create cascading problems across dependent services. While that outage affected AWS’s internal DNS infrastructure rather than Route 53, it demonstrates why DNS reliability matters for Amazon’s business. Using Route 53 for amazon.com would align its most visible domain with the DNS service it recommends to customers.

The Importance of DNS Monitoring

Whether you’re using Route 53, UltraDNS, or any other DNS provider, proactive monitoring remains essential. The AWS outage demonstrated how DNS issues can rapidly cascade, impacting services that rely on DNS resolution. Without monitoring, DNS problems often go undetected until users report failures.

DNS Check provides continuous monitoring for your DNS records, alerting you immediately when issues occur. Our service monitors authoritative nameservers from multiple global locations, ensuring that they respond correctly and return the expected values. When DNS problems arise, let DNS Check notify you before your customers do.

We eat our own dog food by monitoring our own DNS infrastructure with DNS Check. This means we rely on the same monitoring, alerting, and diagnostic tools that we provide to customers. When we improve DNS Check, we directly benefit from those improvements ourselves.

Ready to add DNS monitoring to your infrastructure? Sign up for a free DNS Check account and start monitoring your critical DNS records today. Whether you’re running on AWS, managing your own infrastructure, or using any other provider, DNS Check helps you catch DNS issues before they cascade into larger problems.

In the beginning was the work. The work was done. The work was real. Then, somewhere along the way, work became just motion.

It was like virtue signaling—only worse. At work, I practiced another kind of signaling: innovation signaling. Everyone knows innovation is the ultimate corporate virtue. For years, it wasn’t innovation itself but the signaling of it that I performed. Innovation signaling was my job.

And not just mine.

At Mastercard, I made around $250,000 a year. Over six years, my title changed—Enterprise Architect, Director of Strategy, Principal of Technology. When you’re an engineer, “Principal” is the ceiling if you’re not interested in managing people, and I hit it early. With nowhere to go upward, I moved sideways instead—new bosses, flights to Manila, Dubai, London, and headquarters in New York.

There was movement—through airports, through inboxes. Emails received, emails sent. We gathered in front of whiteboards, drawing the shapes we learned in kindergarten: squares, circles, triangles, arrows connecting them. Each stood for something—systems, messages, networks, the physical, logical, or business layers of whatever new innovation we were trying to invent. When it became too obvious that it wasn’t new, we said we were reinventing. When even that felt untrue, we called it reframing, repurposing, reusing.

What we produced was usually an abstraction of what already existed, wrapped in something new—sometimes just new buzzwords. Because you have to move—even when you’re not inventing anything. You have to check the box, upload the file to an internal shared-drive graveyard—a proof of motion, a justification to others and to ourselves that work had been done. That the high salary reflected merit. That it was earned. That it didn’t come at the cost of something else.

I don’t know when I started noticing that all the movement was the same kind of nothing. Maybe it had started disappearing even earlier, and I just hadn’t seen it—because I was anchored to a different time, blinded by my own expectations of what work was supposed to be. Maybe I was still learning, and I mistook learning for doing. There was a lag in perception. I’m just not sure what caused it.

It’s not a great revelation—David Graeber wrote Bullshit Jobs back in 2018. But we were technologists. Bullshit jobs were for administrators and bureaucrats, for consultants and life coaches, for people selling insurance or purpose. Not for us.

At first I thought it was just a short-term lull. Maybe my team was signaling innovation this year, but other teams might do something real. Or if not them, then surely the company. But there was nothing.

I moved everywhere, touched projects, asked people: “So what are you working on?” Every conversation followed the same arc: “What? Then what? So what?”

Sometimes work looped back on itself like a recursive function. Sometimes it was a dead-end street. Worst of all—a highway that ends midair.

It never added up to anything.

I started checking the company’s press releases. Everything sounded groundbreaking. Blockchain! Cutting-edge innovation!

But it wasn’t. I knew what those projects actually delivered because I was leading some of them. When I came across a press release I wasn’t sure about, I started feeding them through AI.

Copy.

“Is this true innovation or innovation signaling?”

Paste.

One by one, every single one of them came back as innovation signaling. Every. Single. One.

The job of almost everyone I worked with at Mastercard for six years was the same as that of the marketing team writing press releases. We were all spinning, packaging, messaging. The only difference was our audience. I took the spin upward—to my boss and senior leadership. That I was worth keeping. That I was worth $250,000, plus benefits, equity, and remote work. The marketing team took it outward—to the public, to shareholders. To you.

It’s not so obvious. You see logo changes, a new chime when you check out, a slick Super Bowl ad, your card made to look like titanium. But what’s behind all that is old. Mastercard’s “switch”—the company’s bread and butter, the monolithic system that authorizes, clears, and settles transactions—was built during the Nixon era. It’s still the same.

But there is always something that can be pushed out as transformative, digital-first, next-generation, seamless, future-ready, AI-powered, priceless. But it was the same thing as before—just repackaged, rebranded, abstracted. You thought it was new. We pretended it was new.

Later, I moved on from Mastercard and joined consulting companies. More travel. I touched more companies. Banking, financial services, fintech, consulting—saturated with people signaling innovation.

Financial gatekeepers: Experian, TransUnion, Equifax, FIS, Fiserv, PayPal, Stripe. They don’t innovate; they extract.

Internet and cloud infrastructure: Equinix, Digital Realty, Cloudflare, Akamai. They own the digital roads and charge tolls.

Logistics monopolies: UPS, FedEx, Union Pacific, BNSF. Generating private profits on public dependence.

Healthcare and identity gatekeeping: Epic Systems, Cerner, UnitedHealth, ID.me, LexisNexis. They control access to health and identity, but not for the public good.

Capitalism shouldn’t tolerate this kind of work across so many corporations for long. There’s competition, there’s supposed to be rational choice. Customers vote with their feet. Stop innovating, and they should go elsewhere.

But these companies do not just last. They thrive even though they don’t innovate. Because of the digital machinery they inherited. Because of network effects, barriers to entry, locked-in customers, hostile acquisitions.

The companies I worked for made plenty of money. No matter what happened—COVID, mass layoffs, war in Ukraine, any global crisis—someone would always say: “Well, our cash coffers look good.”

We could weather any storm—stagnation, stagflation, shrinkflation, inflation, hyperinflation, recession. You name it.

Bonuses. Promotions. Record profits. The company’s coffers stay full.

These companies don’t just survive. They thrive.

Economist Tyler Cowen has asked: What happens when two-thirds of the economy is stagnant?

I think what he identified on the macro scale, I experienced on the micro level. How much of the white collar economy is actually fake?

I think I was trapped in the stagnant two-thirds. Then again, maybe “trap” isn’t the right word. I was making $250,000 a year. Some might call that floating.

For some reason, I keep thinking of that drifting, aimless plastic bag in American Beauty. So free—yet still just a plastic bag. Floating. Polluting. Empty.

Sarah Majdov is a computer engineer and technologist who spent years in what she calls the “Goldilocks position” of corporate life—right in the middle, high enough to glimpse strategy, low enough to understand execution. She is the author of Fatamorgana.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

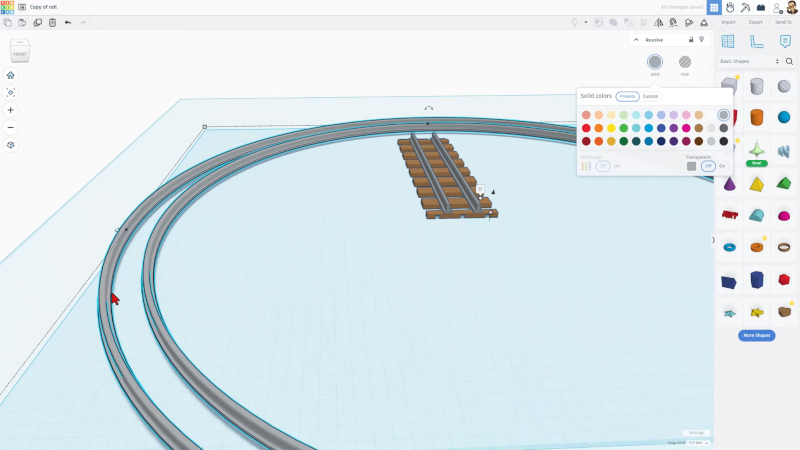

It is easy to write off Tinkercad as a kid’s toy. It is easy enough for kids to learn and it uses bright colors looking more like a video game than a CAD tool. We use a variety of CAD tools, but for something quick, sometimes Tinkercad is just the ticket. Earlier this year, Tinkercad got a sketch feature, something many other CAD programs have and, now, you can even revolve the sketch to form complex objects. Tinkercad guru [HL ModTech] shows you how in the video below.

It wasn’t long ago that we needed to cut an irregular shape out of an STL and we found the sketch feature whic was perfect for that purpose. If you’ve used other CAD tools, you’ll know that sketches are typically 2D shapes that get changed into a 3D shape. The traditional thing is to simply extrude it, so if you draw a circle in 2D, you get a cylinder.

However, you can also revolve a profile around a center point. In that case, a circle would give you a torus or, you know, a doughnut-shape. In Tinkercad these are two different tools.

In the video, you can see how the revolve works. One nice feature is that in the top right corner is a live preview of what your shape will look like after revolving. The video shows a classic example — a chess piece. If you want to see something more practical, he also has a project to create train tracks using the new feature.

If you want to learn more about Tinkercad, you can do worse than watch all of [HL ModTech’s] videos. You can do some pretty amazing things with nothing more than a Web browser.

Tinkercad can even do parameters, sort of. If you virtually attended Remoteacon (the COVID-19 version of Supercon) you already knew that Tinkercad isn’t just for kid stuff.