I attended the AI+Education Summit at Stanford last week, the fourth year for the event and the first year for me. Organizer Isabelle Hau invited researchers, philanthropists, and a large contingent of teachers and students, all of them participating in panels throughout the day. That mix—heavier on practitioners than edtech professionals—gave me lots to think about on my drive home. Here are several of my takeaways.

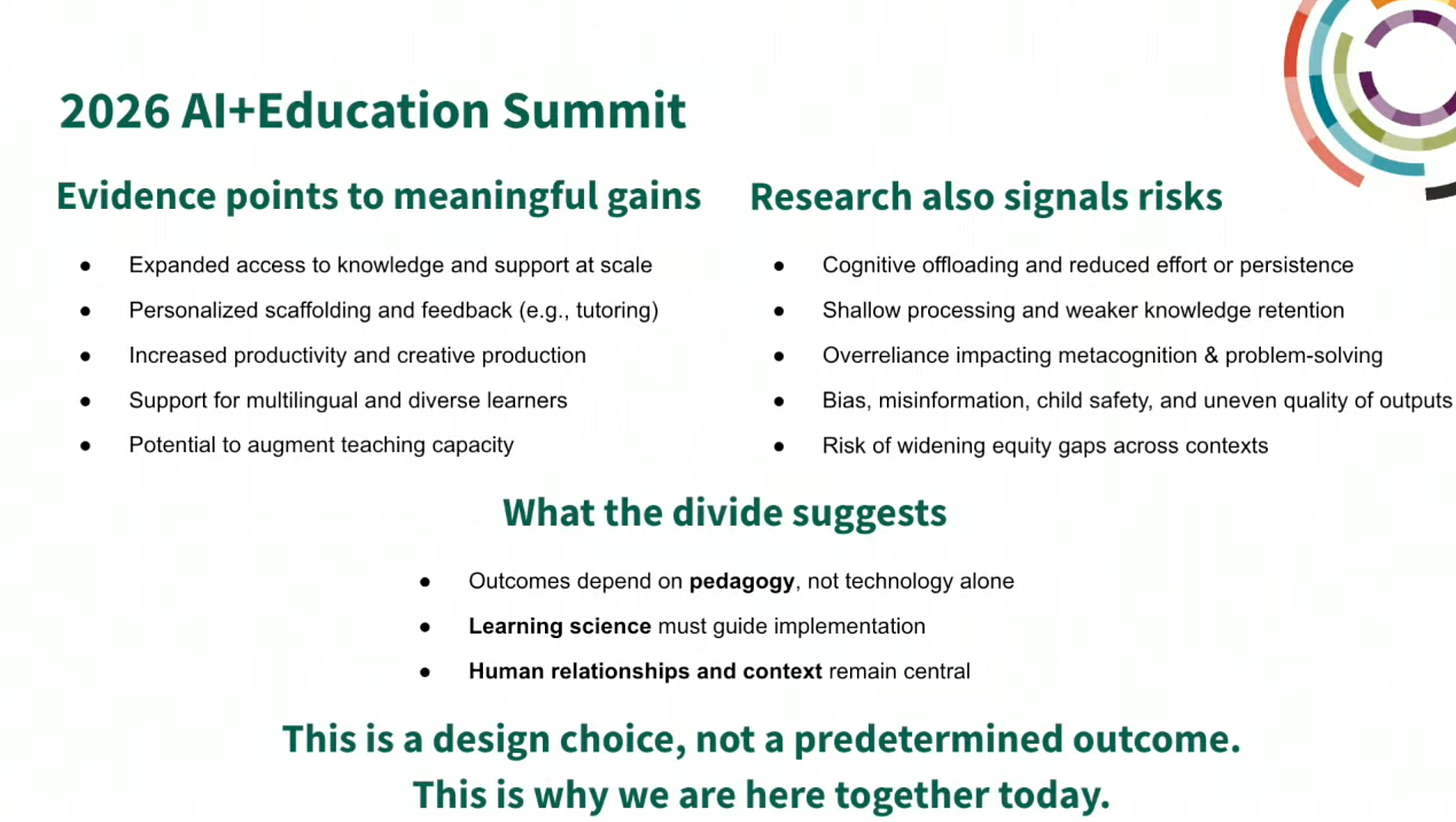

¶ The party is sobering up. The triumphalism of 2023 is out. The edtech rapture is no longer just one more model release away. Instead, from the first slide of the Summit above, panelists frequently argued that any learning gains from AI will be contingent on local implementation and just as likely to result in learning losses, such as those in the second column of the slide.

¶ Stanford’s Guilherme Lichand presented one of those learning losses with his team’s paper, “GenAI Can Harm Learning Despite Guardrails: Evidence from Middle-School Creativity.” His study replicated previous findings that kids do better on certain tasks with AI assistance in the near-term—creative tasks, in his case—and worse later when the tool is taken away. “Already pretty bad news,” Lichand said. But when he gave the students a transfer task, the students who had AI and had it taken away saw negative transfer. “Four-fold,” said Lichand. What’s happening here? Lichand:

It’s not just persistence. It’s a little bit about how you don’t have as much fun doing it, but most importantly, you start thinking that AI is more creative than you. And the negative effects are concentrated on those kids who really think that AI became more creative than them.

A paper I’ll be interested in reading. This was using a custom AI model, as well, one with guardrails to prevent the LLM from solving the tasks for students, the same kind of “tutor modes” we’ve seen from Google, Anthropic, OpenAI, Khan Academy, etc.

¶ Teacher Michael Taubman had the line that brought down the house.

In the last year or so, it’s really started to feel like we have 45 minutes together and the together part is what’s really mattering now. We can have screens involved. We can use AI. We should sometimes. But that is a human space. The classroom is taking on an almost sacred dimension for me now. It’s people gathering together to be young and human together, and grow up together, and learn to argue in a very complicated country together, and I think that is increasingly a space that education should be exploring in addition to pedagogy and content.

¶ Venture capitalist Miriam Rivera urged us to consider the nexus of technology and eugenics that originated in the Silicon Valley:

I have a lot of optimism and a lot of fear of where AI can take us as a society. Silicon Valley has had a long history of really anti-social kinds of movements including in the earliest days of the semi-conductor, a real belief that there are just different classes of humans and some of them are better than others. I can see that happening with some of the technology champions in AI.

Rivera kept bringing it, asking the crowd to consider whether or not they understand the world they are trying to change:

But my sense is there is such a bifurcation in our country about how people know each other. I used to say that church was the most segregated hour in America. I just think that we’ve just gotten more hours segregated in America. And that people often are only interacting with people in their same class, race, level of education. Sometimes I’ve had a party one time, and I thought, my God, everybody here has a master’s degree at least. That’s just not the real world.

And I am fortunate in that because of my life history, that’s not the only world that I inhabit. But I think for many of us and our students here, that is the world that they primarily inhabit, and they have very little exposure to the real world and to the real needs of a lot of Americans, the majority of whom are in financial situations that don’t allow them to have a $400 emergency, like their car breaks down. That can really push them over the edge.

Related: Michael Taubman’s comments above!

¶ Former Stanford President John Hennessy closed the day with a debate between various education and technology luminaries. His opening question was a good one:

How many people remember the MOOC revolution that was going to completely change K-12 education? Why is this time really different? What fundamentally about the technology could be transformative?

This was an important question, especially given the fact that many of the same people at the same university on the same stage had championed the MOOC movement ten years ago. Answers from the panelists:

Stanford professor Susanna Loeb:

I think the ability to generate is one thing. We didn’t have that before.

Rebecca Winthrop, author of The Disengaged Teen:

Schools did not invite this technology into their classroom like MOOCs. It showed up.

Neerav Kingsland, Strategic Initiatives at Anthropic:

This might be the most powerful technology humanity has ever created and so we should at least have some assumption and curiosity that that would have a big impact on education—both the opportunities and risks.

Shantanu Sinha, Google for Education, former COO of Khan Academy:

I’d actually disagree with the premise of the question that education technology hasn’t had a transformative impact over the last 10 years.

Sinha related an anecdote about a girl from Afghanistan who was able to further her schooling thanks to the availability of MOOC-style videos, which is an inspiring story, of course, but quite a different definition of “transformation” than “there will be only 10 universities in the world” or “a free, world‑class education for anyone, anywhere” or Hennessy’s own prediction (unmentioned by anyone) that “there is a tsunami coming” for higher education.

After Sinha described the creation of LearnLM at Google, a version of their Gemini LLM that won’t give students the answer even if asked, Rebecca Winthrop said, “What kid is gonna pick the learn one and not the give-me-the-answer one?”

Susanna Loeb responded to all this chatbot chatter by saying:

I do think we have to overcome the idea that education is just like feeding information at the right level to students. Because that is just one important part of what we do, but not the main thing.

Later, Kingsland gave a charge to edtech professionals:

The technology is, I think, about there, but we don’t yet have the product right. And so what would be amazing, I think, and transformative from AI is, if in a couple of years we had a AI tutor that worked with most kids most of the time, most subjects, that we had it well-researched, and that it didn’t degrade on mental health or disempowerment or all these issues we’ve talked on.

Look—this is more or less how the same crowd talked about MOOCs ten years ago. Copy and paste. And AI tutors will fall short of the same bar for the same reason MOOCs did: it’s humans who help humans do hard things. Ever thus. And so many of these technologies—by accident or design—fit a bell jar around the student. They put the kid into an airtight container with the technology inside and every other human outside. That’s all you need to know about their odds of success.

It’ll be another set of panelists in another ten years scratching their heads over the failure of chatbot tutors to transform K-12 education, each panelist now promising the audience that AR / VR / wearables / neural implants / et cetera will be different this time. It simply will.

Introduction

Eighty-four percent of high school students now use generative AI for schoolwork.¹ Teachers can no longer tell whether a competent essay reflects genuine learning or a 30-second ChatGPT prompt. The assessment system they’re operating in, one that measured learning by evaluating outputs, was designed before this technology existed.

Teachers are already trying to redesign curriculum, assessment, and practice for this new reality. But they’re doing it alone, at 9pm, without tools that actually help.

I spent the last few months trying to understand why and what I found wasn’t surprising, exactly, but it was clarifying: the AI products flooding the education market generate worksheets and lesson plans, but that’s not what teachers are struggling with. The hard work is figuring out how to teach when the old assignments can be gamed and the old assessments no longer prove understanding. Current tools don’t touch that problem.

Based on interviews with eight K-12 teachers and analysis of 350+ comments in online teacher communities, I found three patterns that explain why current AI tools fail teachers and what it would take to build ones they’d actually adopt. The answer isn’t more content generation. It’s tools that act as thinking partners where AI helps teachers reason through the redesign work this moment demands.

The Broken Game

For most of educational history, producing the right output served as reasonable evidence that a student understood the material. If a student wrote a coherent essay, they probably knew how to write. If they solved a problem correctly, they probably understood the underlying concepts. The output was a reliable proxy for understanding.

But now that ChatGPT can generate an entire essay in five seconds, that proxy no longer holds. A student who submits a coherent essay might have written it themselves, revised an AI draft, or copied one wholesale. The traditional system can’t tell the difference.

This breaks the game.

Students aren’t cheating in the way we traditionally understand it. They’re using available tools to win a game whose rules no longer make sense. And the asymmetry here matters since students have already changed their behavior. They have AI in their pockets and use it daily. Whether that constitutes “adapting” or merely “gaming the system in new ways” depends on the student. Some are using AI as a crutch that bypasses thinking. Others are genuinely learning to leverage it. Most are somewhere in between, figuring it out without much guidance.

Meanwhile, teachers are still operating the old system: grading essays that might be AI-generated, assigning problem sets that can be solved in seconds, trying to assess understanding through outputs that no longer prove anything. They’re refereeing a broken game without the tools to redesign it.

The response can’t be banning AI or punishing students for using it. Those are losing battles. The response is redesigning the game itself and rethinking what we assess, how we assess it, and how students practice.

Teachers already sense this. In my interviews, they described the same realization again and again that their old assignments don’t work anymore, their old assessments can be gamed, and they’re not sure what to do about it. They are not resistant to change but they are overwhelmed by the scope of what needs to change, and they’re doing it without support.

This matters beyond one industry. While K-12 EdTech is a $20 billion market, and every major AI lab is positioning for it, the real stakes are larger. When knowledge is instantly accessible and outputs are trivially producible, what does it even mean to learn? The companies building educational AI aren’t just selling software, that’s just a means to an end. They’re shaping the answer to that question.

And right now, they’re getting it wrong.

What Teachers Actually Need

The conventional explanation for uneven AI adoption is that teachers resist change. But my research surfaced a different explanation. Teachers aren’t resistant to AI, they’re resistant to AI that doesn’t help them do the actual hard work.

So, what is the ‘hard work’, exactly?

Teacher work falls into two categories. The first is administrative: entering grades, formatting documents, drafting routine communications. The second is the core of the job: designing curriculum, assessing student understanding, providing feedback that changes how students think, diagnosing what a particular student needs next. This second category is how teachers actually teach.

Current AI tools focus almost entirely on the first category. They generate lesson plans, create worksheets, and draft parent emails. Teachers find this useful. It surfaces ideas quickly, especially when colleagues aren’t available to bounce ideas off of. But administrative efficiency isn’t what teachers are struggling with.

The hard problems are pedagogical. How do you redesign an essay assignment when the old prompt can be completed by AI in 30 seconds? How do you assess understanding when AI can produce correct-looking outputs? How do you structure practice so students develop genuine understanding rather than skip the struggle that builds it?

These questions require deep thinking. And most teachers have to work through them alone. They don’t have a curriculum expert available at 9pm when planning tomorrow’s lesson, or a colleague who knows the research, knows their students, and can reason through these tradeoffs with them in real time.

AI could be that thinking partner. That’s the opportunity current tools are missing.

Three Patterns from the Classroom

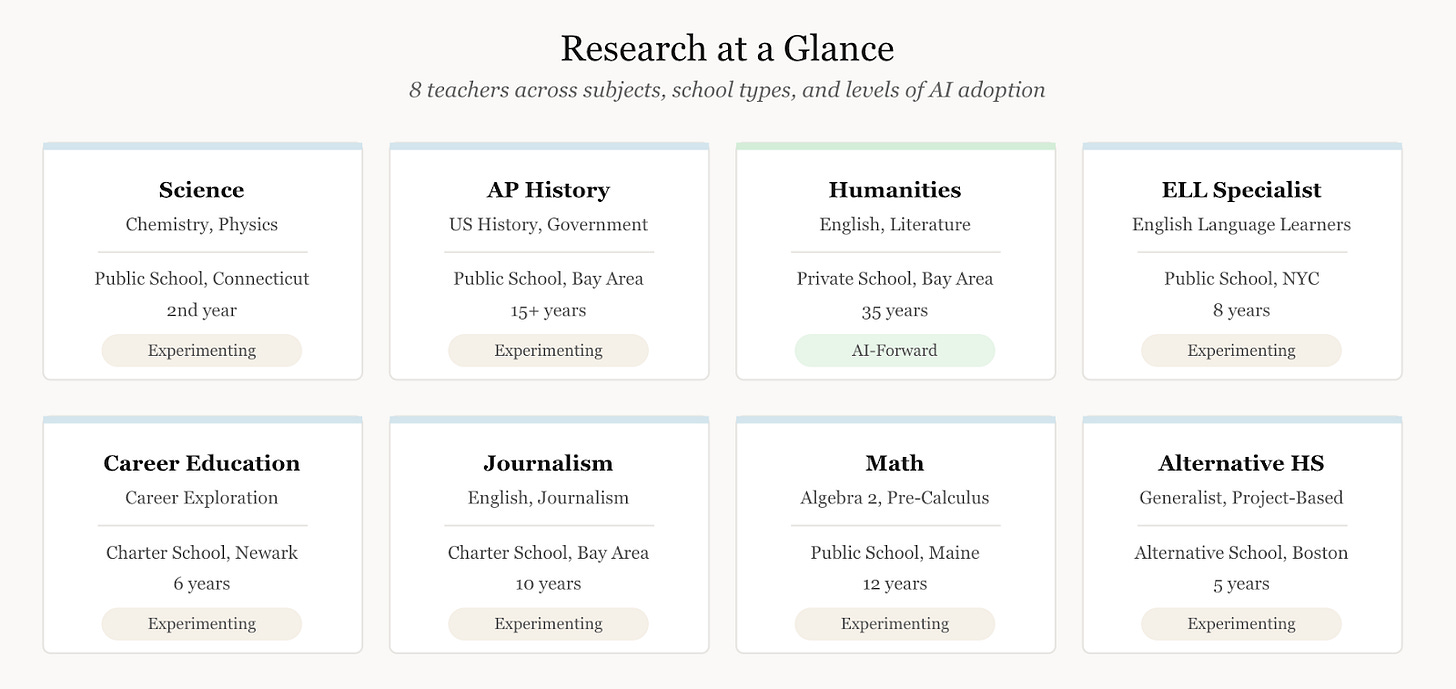

To understand why current tools miss the mark, I interviewed eight K-12 teachers across subjects, school types, and levels of AI adoption. I then analyzed 350+ comments in online teacher communities to test whether their experiences reflected broader patterns or idiosyncratic views.

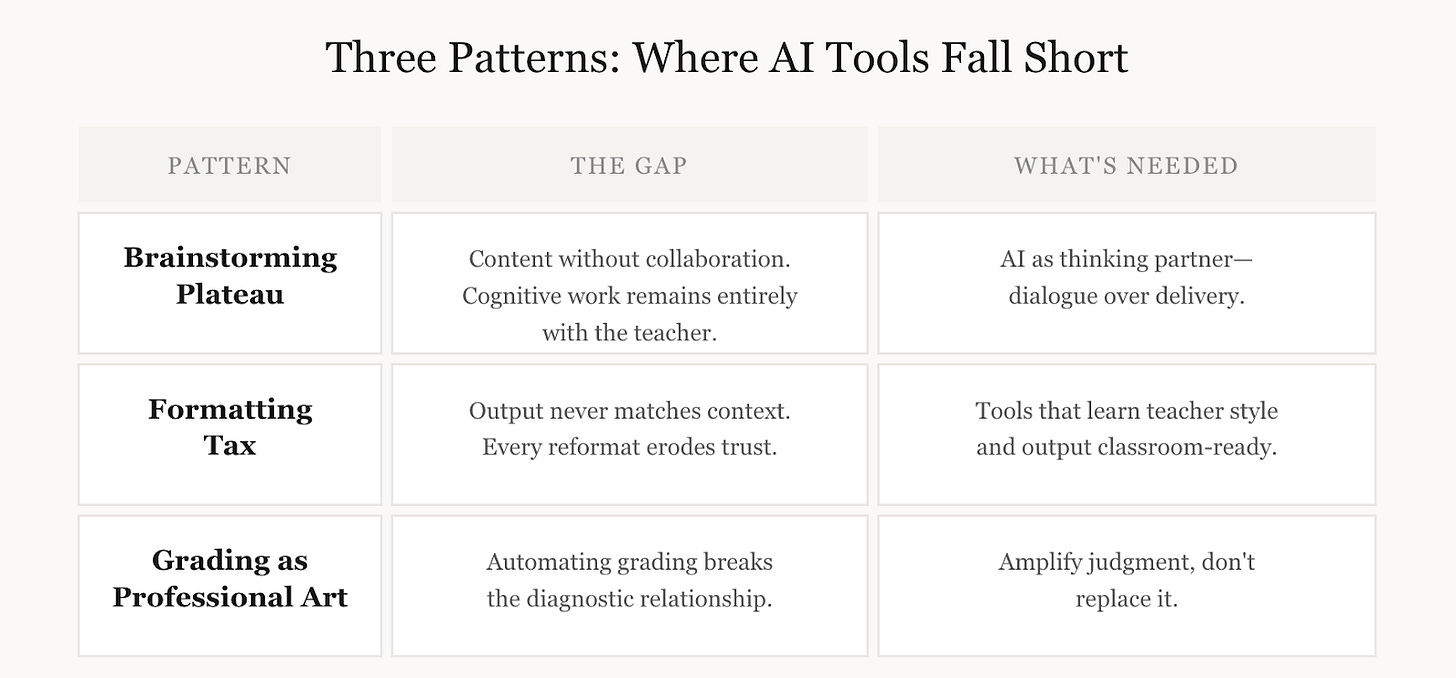

What I found was remarkably consistent. Three patterns kept emerging, and each one reveals a gap between what teachers need and what current AI tools provide.

Pattern 1: The Brainstorming Plateau

Every teacher I interviewed used AI for brainstorming. It’s the universal entry point. “Give me ten practice problems.” “Suggest some activities for this unit.” “What are some real-world connections I could make?” Teachers find this useful because it surfaces ideas quickly when colleagues aren’t available.

But that’s where it stops.

One math teacher described the ceiling bluntly. “Lesson planning, I find to be not very useful. Does it save time or does it not save time? I think it does not save time, because if you are using big chunks, you spend a lot of time going back over them to make sure that they are good, that they don’t have holes.”

He wasn’t alone. This pattern appeared across all eight interviews and echoed throughout the Reddit threads I analyzed. Teachers described the same ceiling again and again. “The worksheets it made for me took longer to fix than what I could have just made from scratch.”

Notice what they’re highlighting is that AI tools produce content that then they have to evaluate alone. They aren’t reasoning through curriculum decisions with AI, they’re cleaning up after it. The cognitive work, the hard part, remains entirely theirs and there is now also incremental work.

A genuine thinking partner would work differently. Not just “here’s a draft assignment” but “I notice your old essay prompt can be completed by AI in 30 seconds. What if we redesigned it so students have to draw on class discussions, articulate their own reasoning, reflect on what they actually understand versus what AI could generate for them? Here are a few options. Which direction fits what you’re trying to teach?”

That’s the kind of collaboration teachers want.

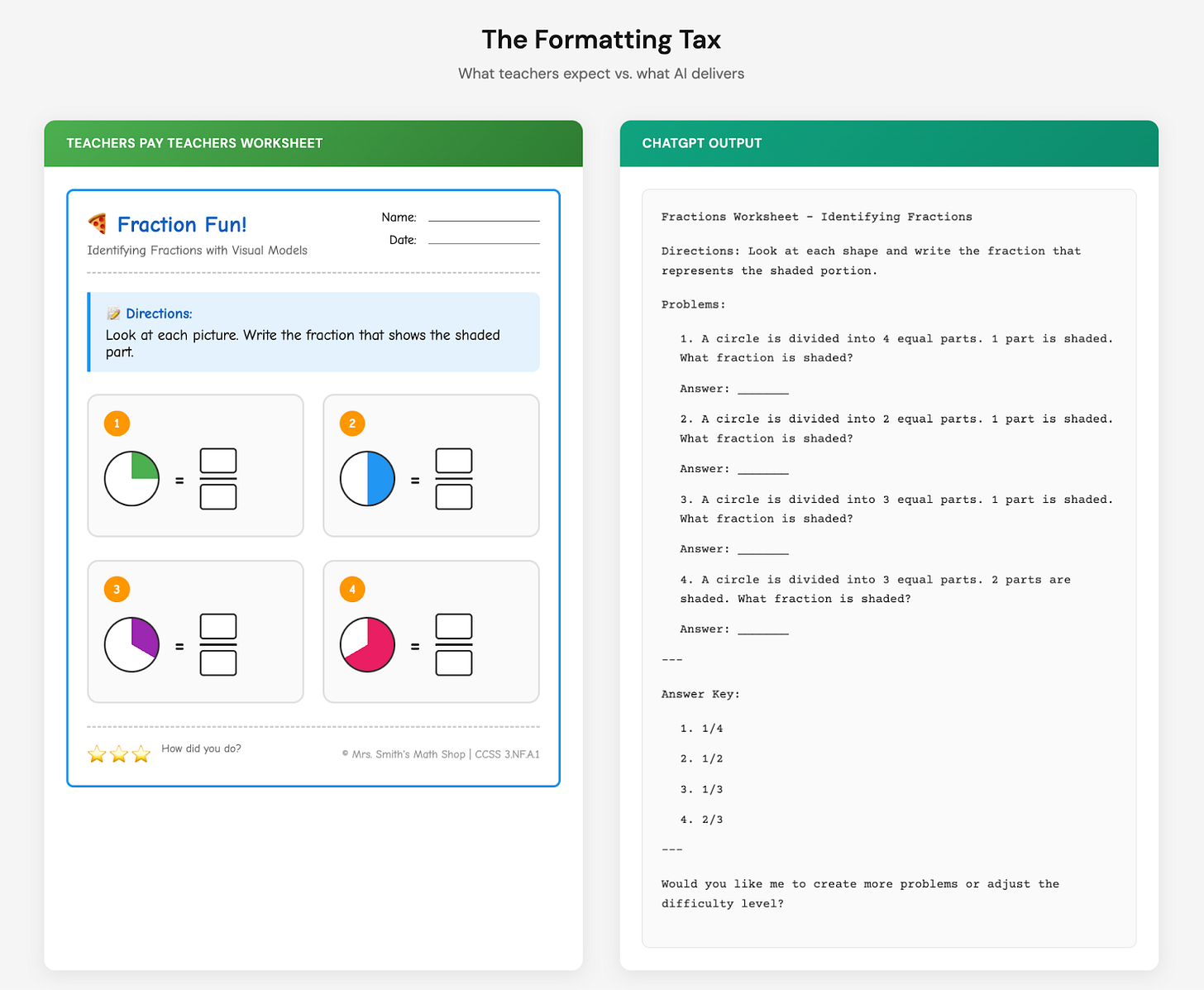

Pattern 2: The Formatting Tax

Even if AI could be that thinking partner, teachers would need to trust it first. And trust is exactly what current tools are squandering.

A recurring frustration across my interviews and Reddit threads is that AI generates content quickly, but the output rarely matches classroom needs. Teachers described spending significant time reformatting, fixing notation that didn’t render correctly, and restructuring content to fit their established norms. One teacher put it simply, “by the time you’ve messed around with prompts and edited the results into something usable, you could’ve just made it yourself.”

This might seem minor, a ‘fit-and-finish’ problem, but it highlights a broader trust problem.

Every time a teacher reformats AI output, they are reminded that this tool doesn’t know my classroom. It doesn’t understand my context and it produces generic content, expecting me to do the translation.

And this points to something deeper. Teachers know that these tools weren’t designed for classrooms. They were built for enterprise use cases and retrofitted for education, optimizing for impressive demos to district leaders rather than daily classroom use. Teachers haven’t been treated as partners in shaping what AI-augmented teaching should look like.

A tool that understood context would work differently. Not “here’s a worksheet on fractions” but “here’s a worksheet formatted the way you like, with the name field in the top right corner, more white space for showing work, vocabulary adjusted for your English language learners. I noticed your last unit emphasized visual models, so I’ve included those. Want me to adjust the difficulty progression?”

That’s what earning trust looks like.

Pattern 3: Grading as Diagnostic Work

And even then, trust is only part of the story. Even well-designed tools will fail if they try to automate the wrong things.

When it comes to grading, teachers are willing to experiment with AI for low-stakes feedback (exit tickets, rough drafts, etc.). But when they do, the results disappoint. “The feedback was just not accurate,” one teacher told me. “It wasn’t giving a bad signal, but it wasn’t giving them the things to focus on either.”

For teachers, the problem is that the AI feedback is just too generic.

One English teacher shared why this matters, “I know who could do what. Some students, if they get to be proficient, that’s amazing. Others need to push further. That’s dependent on their starting point, not something I see as a negative.”

This is why teachers resist automating grading even when they’re exhausted by it. Grading isn’t just about assigning scores, it’s diagnostic work. When a teacher reads student work, they’re asking themselves: what does this student understand? What did I do or not do that contributed to this outcome? How does this represent growth or regression for this particular student? Grading is how teachers know what to do tomorrow for their students.

A tool that understood this would work differently. Not “here’s a grade and some feedback” but “I noticed three students made the same error on question 4. They’re confusing correlation with causation. Here’s a mini-lesson that addresses that misconception. Also, Marcus showed significant improvement on thesis statements compared to last month. And Priya’s response suggests she might be ready for more challenging material. What would you like to prioritize?”

That’s a thinking partner that helps teachers see patterns so they can make better decisions. The resistance to AI grading isn’t technophobia so much as an intuition that the diagnostic work is too important to outsource.

The Equity Dimension

Now, these patterns don’t affect all students equally… and this is the part that keeps me up at night.

Some students will figure out how to use AI productively. They have adults at home who can guide them, or the metacognitive skills to self-regulate. But many won’t. Research already shows that first-generation college students are less confident in appropriate AI use cases than their continuing-generation peers.² The gap is already forming.

This is an equity problem hiding in plain sight. When AI tools fail teachers, they fail all students, but they fail some students more than others. The students who most need guidance on how to use AI productively are least likely to get it outside of school.

Teachers are the only scalable intervention, but only if they can see what’s happening: which students are over-relying on AI as a crutch, which are underutilizing it, and which are developing genuine capability. Without tools that surface these patterns, the redesign helps the students who were already going to be fine.

What Would Actually Work

These three patterns reinforce the gap that tools are currently designed to generate content when teachers need help thinking through problems. Years of context-blind, teacher-replacing products have eroded the trust in this critical population.

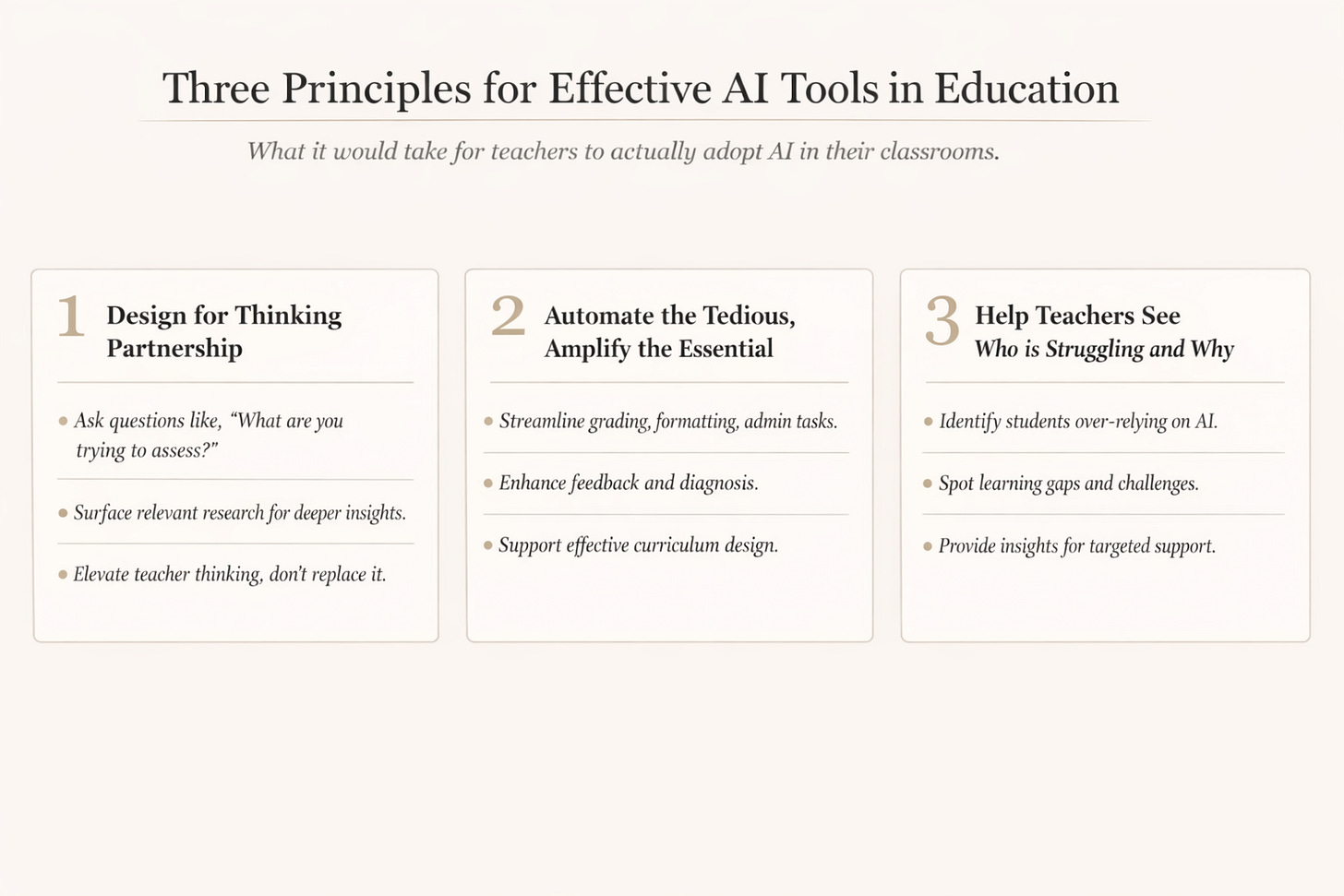

So what would it actually take to build tools teachers adopt? Three principles emerge from my research.

Design for thinking partnership, not content generation. The measure of success isn’t content volume. It’s whether teachers make better decisions. That means tools that engage in dialogue rather than just produce drafts. Tools that ask “what are you trying to assess?” before generating an assignment. Tools that surface relevant research when teachers are wrestling with hard questions. The goal is elevating teacher thinking, not replacing it.

Automate the tedious, amplify the essential. Teachers want some tasks done faster such as entering grades, formatting documents, drafting routine communications. Other tasks they want to do better: diagnosing understanding, designing curriculum, providing feedback that changes how students think. The first category is ripe for automation. The second requires amplification where AI enhances teacher capability rather than substituting for it. “AI can surface patterns across student work” opens doors that “AI can grade your essays” closes.

Help teachers see who is struggling and why. Build tools that surface patterns on which students show signs of skipping the thinking, which show gaps that AI is papering over, which are developing genuine capability. This is the diagnostic information teachers need to differentiate instruction and ensure the students who need the most support actually get it.

The Broader Challenge

This is a preview of a challenge that will confront every domain where AI meets skilled human work.

The question of whether AI should replace human judgment or augment it isn’t abstract. It gets answered, concretely, in every product decision. Do you build a tool that grades essays, or one that helps teachers understand what students are struggling with? Do you build a tool that generates lesson plans, or one that helps teachers reason through pedagogical tradeoffs?

The first approach is easier to demo and easier to sell. The second is harder to build but more likely to actually work, and more likely to be adopted by the people who matter.

Education is a particularly revealing test case because the stakes are legible. When AI replaces teacher judgment in ways that don’t work, students suffer visibly. But the same dynamic plays out in medicine, law, management, and every domain where expertise involves judgment, not just information retrieval.

The companies that figure out how to build AI that genuinely augments expert judgment, rather than producing impressive demos that experts eventually abandon, will have learned something transferable. And very, very important.

Conclusion

Students are developing their relationship with AI right now, largely without deliberate guidance. They’re playing a broken game, and they know it. Whether they learn to use AI as a crutch that bypasses thinking or as a tool that augments it depends on whether teachers can redesign the game for this new reality.

That won’t happen with better worksheets. It requires tools designed with teachers, not for them. Tools that treat teachers as collaborators in figuring out what AI-augmented education should look like, rather than as end-users to be sold to.

What would that look like in practice? A tool that asks teachers what they’re struggling with before offering solutions. A tool that remembers their classroom context, their students, their constraints. A tool that surfaces research and options rather than just producing content. A tool that helps them see patterns in student work they might have missed. A tool that makes the hard work of teaching, the judgment, the diagnosis, the redesign, a little less lonely.

The teachers I interviewed are ready to do this work and they’re not waiting for permission.

They’re waiting for tools worthy of the challenge.

Research Methodology

This essay draws on semi-structured interviews with eight K-12 teachers across different subjects (math, English, science, history, journalism, career education), school types (public, charter, private), and levels of AI adoption. All quotes are anonymized to protect participant privacy.

To test generalizability, I analyzed 350+ comments in online teacher communities, particularly Reddit’s r/Teachers. I intentionally selected high-engagement threads representing both enthusiasm and skepticism about AI tools. A limitation worth noting is that high-engagement threads tend to surface the most articulate and polarized voices, which may not represent typical teacher experiences. Still, the consistency between interview data and online discourse, despite different geographic contexts and school types, suggests these patterns reflect meaningful dynamics in K-12 AI adoption.

—

¹ College Board Research, “U.S. High School Students’ Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence,” June 2025. The study found 84% of high school students use GenAI tools for schoolwork as of May 2025, with 69% specifically using ChatGPT.

² Inside Higher Ed Student Voice Survey, August 2025.

—

About the Author: Akanksha has over a decade of experience in education technology, including classroom teaching through Teach for America, school leadership roles at Charter Schools, curriculum design and operations leadership at Juni Learning, and AI strategy work at Multiverse, where she led efforts to scale learning delivery models from 1:30 to 1:300+ ratios while maintaining quality outcomes.

I have to begin by warning you about the content in this piece; while I won’t be dwelling on any specifics, this will necessarily be a broad discussion about some of the most disturbing topics imaginable. I resent that I have to give you that warning, but I’m forced to because of the choices that the Big AI companies have made that affect children. I don’t say this lightly. But this is the point we must reckon with if we are having an honest conversation about contemporary technology.

Let me get the worst of it out of the way right up front, and then we can move on to understanding how this happened. ChatGPT has repeatedly produced output that encouraged and incited children to end their own lives. Grok’s AI generates sexualized imagery of children, which the company makes available commercially to paid subscribers.

It used to be that encouraging children to self-harm, or producing sexualized imagery of children, were universally agreed upon as being amongst the worst things one could do in society. These were among the rare truly non-partisan, unifying moral agreements that transcended all social and cultural barriers. And now, some of the world’s biggest and most powerful companies, led by a few of the wealthiest and most powerful men who have ever lived, are violating these rules, for profit, and not only is there little public uproar, it seems as if very few have even noticed.

How did we get here?

The ideas behind a crisis

A perfect storm of factors have combined to lead us towards the worst case scenario for AI. There is now an entire market of commercial products that attack our children, and to understand why, we need to look at the mindset of the people who are creating those products. Here are some of the key motivations that drove them to this point.

1. Everyone feels desperately behind and wants to catch up

There’s an old adage from Intel’s founder Andy Grove that people in Silicon Valley used to love to quote: “Only the paranoid survive”. This attitude persists, with leaders absolutely convinced that everything is a zero-sum game, and any perceived success by another company is an existential threat to one’s own future.

At Google, the company’s researchers had published the fundamental paper underlying the creation of LLMs in 2017, but hadn’t capitalized on that invention by making a successful consumer product by 2022, when OpenAI released ChatGPT. Within Google leadership (and amongst the big tech tycoons), the fact that OpenAI was able to have a hit product with this technology was seen as a grave failure by Google, despite the fact that even OpenAI’s own leadership hadn’t expected ChatGPT to be a big hit upon launch. A crisis ensued within Google in the months that followed.

These kinds of industry narratives have more weight than reality in driving decision-making and investment, and the refrain of “move fast and break things” is still burned into people’s heads, so the end result these days is that shipping any product is okay, as long as it helps you catch up to your competitor. Thus, since Grok is seriously behind its competitors in usage, and of course Grok's CEO Elon Musk is always desperate for attention, they have every incentive to ship a product with a catastrophically toxic design — including one that creates abusive imagery.

2. Accountability is “woke” and must be crushed

Another fundamental article of faith in the last decade amongst tech tycoons (and their fanboys) is that woke culture must be destroyed. They have an amorphous and ever-evolving definition of what “woke” means, but it always includes any measures of accountability. One key example is the trust and safety teams that had been trying to keep all of the major technology platforms from committing the worst harms that their products were capable of producing.

Here, again, Google provides us with useful context. The company had one of the most mature and experienced AI safety research teams in the world at the time when the first paper on the transformer model (LLMs) was published. Right around the time that paper was published, Google also saw one of its engineers publish a sexist screed on gender essentialism designed to bait the company into becoming part of the culture war, which it ham-handedly stumbled directly into. Like so much of Silicon Valley, Google’s leadership did not understand that these campaigns are always attempts to game the refs, and they let themselves be played by these bad actors; within a few years, a backlash had built and they began cutting everyone who had warned about risks around the new AI platforms, including some of the most credible and respected voices in the industry on these issues.

Eliminating those roles was considered vital because these people were blamed for having “slowed down” the company with their silly concerns about things like people’s lives, or the health of the world’s information ecosystem. A lot of the wealthy execs across the industry were absolutely convinced that the reason Google had ended up behind in AI, despite having invented LLMs, was because they had too many “woke” employees, and those employees were too worried about esoteric concerns like people’s well-being.

It does not ever enter the conversation that 1. executives are accountable for the failures that happen at a company, 2. Google had a million other failures during these same years (including those countless redundant messaging apps they kept launching!) that may have had far more to do with their inability to seize the market opportunity and 3. it may be a good thing that Google didn’t rush to market with a product that tells children to harm themselves, and those workers who ended up being fired may have saved Google from that fate!

3. Product managers are veterans of genocidal regimes

The third fact that enabled the creation of pernicious AI products is more subtle, but has more wide-ranging implications once we face it. In the tech industry, product managers are often quietly amongst the most influential figures in determining the influence a company has on culture. (At least until all the product managers are replaced by an LLM being run by their CEO.) At their best, product managers are the people who decide exactly what features and functionality go into a product, synthesizing and coordinating between the disciplines of engineering, marketing, sales, support, research, design, and many other specialties. I’m a product person, so I have a lot of empathy for the challenges of the role, and a healthy respect for the power it can often hold.

But in today’s Silicon Valley, a huge number of the people who act as product managers spent the formative years of their careers in companies like Facebook (now Meta). If those PMs now work at OpenAI, then the moments when they were learning how to practice their craft were spent at a company that made products that directly enabled and accelerated a genocide. That’s not according to me, that’s the opinion of multiple respected international human rights organizations. If you chose to go work at Facebook after the Rohingya genocide had happened, then you were certainly not going to learn from your manager that you should not make products that encourage or incite people to commit violence.

Even when they’re not enabling the worst things in the world, product managers who spend time in these cultures learn more destructive habits, like strategic line-stepping. This is the habit of repeatedly violating their own policies on things like privacy and security, or allowing users to violate platform policies on things like abuse and harassment. This tactic is followed by then feigning surprise when the behavior is caught. After sending out an obligatory apology, they repeat the behavior again a few more times until everyone either gets so used to it that they stop complaining or the continued bad actions drives off the good people, which makes it seem to the media or outside observers that the problem has gone away. Then, they amend their terms of service to say that the formerly-disallowed behavior is now permissible, so that in the future they can say, “See? It doesn’t violate our policy.”

Because so many people in the industry now have these kind of credential on their LinkedIn profiles, their peers can’t easily mention many kinds of ethical concerns when designing a product without implicitly condemning their coworkers. This becomes even more fraught when someone might potentially be unknowingly offending one of their leaders. As a result, it becomes a race to the bottom, where the person with the worst ethical standards on the team determines the standards to which everyone designs their work. As a result, if the prevailing sentiment about creating products at a company is that having millions of users just inevitably means killing some of them (“you’ve got to break a few eggs to make an omelet”), there can be risk to contradicting that idea. Pointing out that, in fact, most platforms on the internet do not harm users in these ways and their creators work very hard to ensure that tech products don’t present a risk to their communities, can end up being a career-limiting move.

4. Compensation is tied to feature adoption

This is a more subtle point, but explains a lot of the incentives and motivations behind so much of what happens with today’s major technology platforms. The introduction or rollout of new capabilities is measured when these companies launch new features, and the success of those rollouts or launches are often tied to the measurements of individual performance for the people who were responsible for those features. These will be measured using metrics like “KPIs” (key performance indicators) or other similar corporate acronyms, all of which basically represent the concept of being rewarded for whether the thing you made was adopted by users in the real world. In the abstract, it makes sense to reward employees based on whether the things they create actually succeed in the market, so that their work is aligned with whatever makes the company succeed.

In practice, people’s incentives and motivations get incredibly distorted over time by these kinds of gamified systems being used to measure their work, especially as it becomes a larger and larger part of their compensation. If you’ve ever wondered why some intrusive AI feature that you never asked for is jumping in front of your cursor when you’re just trying to do a normal task the same way that you’ve been doing it for years, it’s because someone’s KPI was measuring whether you were going to click on that AI button. Much of the time, the system doesn’t distinguish between “I accidentally clicked on this feature while trying to get rid of it” and “I enthusiastically chose to click on this button”. This is what I mean when I say we need an internet of consent.

But you see the grim end game of this kind of thinking, and these kinds of reward systems, when kids’ well-being is on the line. Someone’s compensation may well be tied to a metric or measurement of “how many people used the image generation feature?” without regard to whether that feature was being used to generate imagery of children without consent. Getting a user addicted to a product, even to the point where they’re getting positive reinforcement when discussing the most self-destructive behaviors, will show up in a measurement system as increased engagement — exactly the kind of behavior that most compensation systems reward employees for producing.

5. Their cronies have made it impossible to regulate them

A strange reality of the United States’ sad decline into authoritarianism is that it is presently impossible to create federal regulation to stop the harms that these large AI platforms are causing. Most Americans are not familiar with this level of corruption and crony capitalism, but Trump’s AI Czar David Sacks has an unbelievably broad number of conflicts of interest from his investments across the AI spectrum; it’s impossible to know how many because nobody in the Trump administration follows even the basic legal requirements around disclosure or disinvestment, and the entire corrupt Republican Party in Congress refuses to do their constitutionally-required duty to hold the executive branch accountable for these failures.

As a result, at the behest of the most venal power brokers in Silicon Valley, the Trump administration is insisting on trying to stop all AI regulations at the state level, and of course will have the collusion of the captive Supreme Court to assist in this endeavor. Because they regularly have completely unaccountable and unrecorded conversations, the leaders of the Big AI companies (all of whom attended the Inauguration of this President and support the rampant lawbreaking of this administration with rewards like open bribery) know that there will be no constraints on the products that they launch, and no punishments or accountability if those products cause harm.

All of the pertinent regulatory bodies, from the Federal Trade Commission to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have had their competent leadership replaced by Trump cronies as well, meaning that their agendas are captured and they will not be able to protect citizens from these companies, either.

There will, of course, still be attempts at accountability at the state and local level, and these will wind their way through the courts over time. But the harms will continue in the meantime. And there will be attempts to push back on the international level, both from regulators overseas, and increasingly by governments and consumers outside the United States refusing to use technologies developed in this country. But again, these remedies will take time to mature, and in the meantime, children will still be in harm’s way.

What about the kids?

It used to be such a trope of political campaigns and social movements to say “what about the children?” that it is almost beyond parody. I personally have mocked the phrase because it’s so often deployed in bad faith, to short-circuit complicated topics and suppress debate. But this is that rare circumstance where things are actually not that complicated. Simply discussing the reality of what these products do should be enough.

People will say, “but it’s inevitable! These products will just have these problems sometimes!” And that is simply false. There are already products on the market that don’t have these egregious moral failings. More to the point, even if it were true that these products couldn’t exist without killing or harming children — then that’s a reason not to ship them at all.

If it is, indeed absolutely unavoidable that, for example, ChatGPT has to advocate violence, then let’s simply attach a rule in the code that modifies it to change the object of the violence to be Sam Altman. Or your boss. I suspect that if, suddenly, the chatbot deployed to every laptop at your company had a chance of suggesting that people cause bodily harm to your CEO, people would suddenly figure out a way to fix that bug. But somehow when it makes that suggestion about your 12-year-old, this is an insurmountably complex challenge.

We can expect things to get worse before they get better. OpenAI has already announced that it is going to be allowing people to generate sexual content on its service for a fee later this year. To their credit, when doing so, they stated their policy prohibiting the use of the service to generate images that sexualize children. But the service they’re using to ensure compliance, Thorn, whose product is meant to help protect against such content, was conspicuously silent about Musk’s recent foray into generating sexualized imagery of children. An organization whose entire purpose is preventing this kind of material, where every public message they have put out is decrying this content, somehow falls mute when the world’s richest man carries out the most blatant launch of this capability ever? If even the watchdogs have lost their voice, how are regular people supposed to feel like they have a chance at fighting back?

And then, if no one is reining in OpenAI, and they have to keep up with their competitors, and the competition isn’t worried about silly concerns like ethics, and the other platforms are selling child exploitation material, and all of the product mangers are Meta alumni who know that they can just keep gaming the terms of service if they need to, and laws aren’t being enforced, and all the product managers making the product learned to make decisions while they were at Meta… well, will you be surprised?

How do we move forward?

It should be an industry-stopping scandal that this is the current state of two of the biggest players in the most-hyped, most-funded, most consequential area of the entire business world right now. It should be unfathomable that people are thinking about deploying these technologies in their businesses — in their schools! — or integrating these products into their own platforms. And yet I would bet that the vast majority of people using these products have no idea about these risks or realities of these platforms at all. Even the vast majority of people who work in tech probably are barely aware.

What’s worse is, the majority of people I’ve talked to in tech, who do know about this have not taken a single action about it. Not one.

I’ll be following up with an entire list of suggestions about actions we can take, and ways we can push for accountability for the bad actors who are endangering kids every day. In the meantime, reflect for yourself about this reality. Who will you share this information with? How will this change your view of what these companies are? How will this change the way you make decisions about using these products? Now that you know: what will you do?

I’ve long believed that social media is a suck, and if I didn’t have to use it for my job, I wouldn’t. If it isn’t showing you long paragraphs of hot garbage cosplaying as Socrates from folks who should know better than to put screenshots of discourse on your timeline, it’s some other bullshit. But what doesn’t suck—and honestly feels downright aspirational—is mangaka author comments, which should be the blueprint for how to use social media.

Back in the day, when Borders bookstores were still around, you could flip to the inside cover of a manga volume and read an anecdotal paragraph from creators, like Dragon Ball’s Akira Toriyama writing about spoiling his kids and trying not to get bored making manga. While you can still read lengthier ramblings today, like Chainsaw Man creator Tatsuki Fujimoto recollecting how he ate his girlfriend’s pet fish instead of telling her he killed it, you can also read what a collective of mangaka has to say about their weeks like a curated, pseudo social media feed.

In the modern digital age, authors’ comments are still going strong, preserved online in blog posts where Weekly Shonen Jump’s rotating roster of creators drop diary entries with the same energy as NBA players in a post‑game interview—hands on their hips while on the court, still catching their breath, saying whatever stray thought about their week pops into their heads. Shonen Jump’s author comments, stylized as mangaka musings, are exactly that: a collection of off‑the‑cuff messages from creators published in Weekly Shonen Jump, giving fans a quick peek into their day‑to‑day lives.

Sometimes, author comments are about the chapter they slaved away on in the meat grinder that is weekly manga production, congratulating a creator for finishing their series, or sharing updates about a live-action or anime adaptation. But more often than not, it’s just them posting about random occurrences in their lives and their thoughts about them. Those thoughts can range from One Piece creator Eiichiro Oda praising a very bad variety show as “the pinnacle of human achievement,” Sakamoto Days’ creator updating readers on his progress in Nightreign, everyone’s obsession with butter caramel Pringles, or the emotional arcs of their procurement and piecemeal consumption of choco eggs.

The beauty of the grab-bag randomness of mangaka musings is that they’re oh so brief. They’re unfiltered, shower thoughts-level of relatable, and they paint enough of a picture that you feel better having taken the time to read them. Here are a handful of authors’ comments I like that would go triple platinum as social media posts:

Sure, a lot of these comments read like exasperated asides blurted out because they had to write something on top of drawing 21 pages of their ongoing manga for reader enjoyment. But it's that exact “I’m not gonna hold you” brevity that makes them worth checking out every week. Sometimes it’s just nice to see what someone found worth mentioning, no matter how superfluous it is.

Manga author notes should be the aspiration for how we use social media, because the smallest, most offhand thing is more human than any algorithm-optimized screed rewarding ragebaiting, forced discourse, and low-effort engagement farming sludge we doomscroll past on the daily. So next time you’re about to full-send a post, think to yourself: Do I sound like a manga author comment? If not, delete that shit expeditiously.

I have had it to up to here with what I call AI “woo-woo.”

The breaking point was this headline on Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei’s podcast conversation with The New York Times’ Ross Douthat.

I can dispel Dario Amodei’s doubt. We know that large language models like his company’s Claude are not conscious because the underlying architecture which drives them does not allow for it.

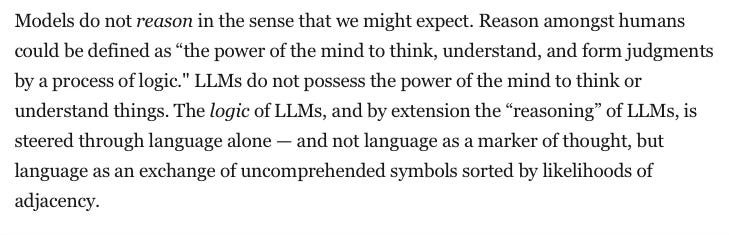

I am aware of and have dipped my toes into the larger debates about consciousness and whether or not we can definitively say whether or not anything is conscious - I’ve read my Daniel Dennett - but these debates, as interesting as they may be in theory are not applicable to the work of large language models. These things do not think, feel, reason or communicate with intention. This is simply a fact of how they work. I shall return to one of my favorite short explainers of this from Eryk Salvaggio and his essay, “A Critique of Pure LLM Reason”:

Could there be an embodied AI someday that has the kinds of capabilities that should give us pause before dismissing them as a mere machine? I don’t know, maybe? I’ve read I, Robot, I’ve watched Ex Machina.

But LLMs are not that, never will be, and yet here is the CEO of a company which just raised another $30 billion dollars, pushing Anthropic’s valuation to $380 billion, making a truly absurd claim.

Amodei has not been the only Anthropic figure on the woo-woo weaving PR tour. Company “philosopher” Amanda Askell has been everywhere, including a recent episode of the Hard Fork podcast in which she talks about her view that shaping Claude is akin to the work of raising a child.

Golly! If the people who are closest to the development of this technology are actively wondering about whether or not the models might be conscious and trying to offer guidance in the role of a parent in shaping its “character,” we’ve got some really powerful stuff here!

Unfortunately, the woo-woo isn’t limited to the direct statements from Anthropic insiders. In a company profile published at the New Yorker, which has much to recommend it as a work of ethnography, but is also infused with woo-woo, Gideon Lewis-Kraus gives in to the impulse to describe a large language model as a “black box,” a description that is simply not true, or is only true if you stretch the definition of “black box” to mean some stuff happens that’s surprising.

In truth, large language models operate as they were theorized in a paper prior to their development. There is no genie that has been released from the bottle (or black box) and floating around the room. There is a piece of technology. This woo-woo is spun in the service of creating a myth (more good stuff from Salvaggio here), a myth which signals to regular folks that we should see ourselves as disempowered in the face of such a thing. Even the people in charge of this stuff can’t really get a hold of it. What hope do the rest of us have?

This disempowerment makes us vulnerable to outsized and unevidenced claims like those in a viral Twitter essay that claimed we’re on the precipice of a disruption in the labor force unlike anything that’s occurred previously, beyond even what we can conceive of. ( fisks the vial essay here.)

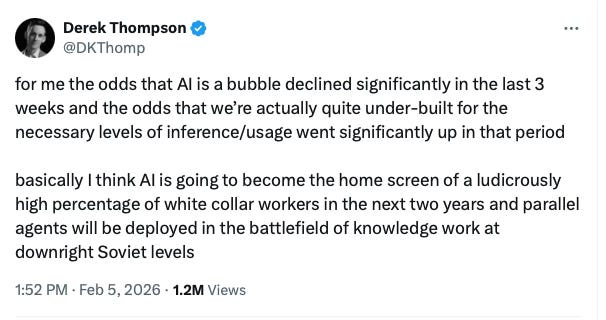

It’s all woo-woo. Even this from the ostensibly sober-minded Derek Thompson is its own form of woo-woo.

We must ask, why is Dario Amodei saying he’s not sure if his LLM is conscious? Three possibilities:

He’s genuinely not very bright or well informed on this stuff.

He’s bullshitting us.

He’s bullshitting himself.

Let’s dismiss number one. When I posted a screen shot of that headline from the Douthat/Amodei podcast conversation on BlueSky, lots of people showed up to just say that Amodei is an idiot, which he is not. It is important not to grant people like Dario Amodei, Sam Altman (OpenAI), or Demis Hassabis (Google) any kind of special oracle status because of their proximity to the technology, but at the same time we must recognize their agency in these discussions. When they say things they are done with knowledge and intent.

In my view, the answer is some combination of 2 and 3. If you have to ask why Dario Amodei might be bullshitting us, here is your answer:

But we also cannot dismiss the notion that he is bullshitting himself. The Lewis-Kraus New Yorker piece paints a picture of a group of people in thrall to their own world views, views which are steeped in Effective Altruism, a movement which tasks themselves with being responsible for saving not just humanity, but the uncountable number of future people. While Anthropic plays down these associations, as true-blue EA’s are deeply concerned about AI killing us all, these delusions of importance appear to be part of the overall DNA.

In his book, More Everything Forever, Adam Becker pokes through the EA movement and finds something strange, cultish, and ultimately contradictory. These are people who intend to preserve humanity by potentially destroying the Earth.

In the past, Amodei has put his (p)doom score - the belief that AI could unleash catastrophic events - at 25%. Consider the tension here. Imagine you are both an Effective Altruist and you are working on technology that you believe could have a one-in-four chance of essentially exterminating humanity. Amodei says he has oriented his company’s priorities around AI safety. But a sincere belief in the danger of AI should lead you to pull the plug on your own project and then advocate forcefully for doing the same to others.

His views are irreconcilable, which is how we know it’s all woo-woo.

We gotta ignore the woo-woo because that’s all it is.

As to why people like Derek Thompson are making massive claims about the future of labor based essentially on personal, anecdotal experience, I think there’s a couple things going on:

More people are finding genuine, interesting, and surprising uses for the technology.

This appears particularly true of Claude Code, which is what Thompson is referring to here. For the uninitiated, Claude Code (and a similar product, Claude Cowork) are self-directing agents that can execute a task after being prompted in plain language instructions. They are, no doubt, amazing applications of this technology and people are finding them useful.

Here’s declaring that after trying Claude Code “everything has changed.” Dan’s work with data visualization in publishing was previously hampered by the challenges of coding for the data sets available to him. Claude Code has removed those frictions. Sinykin sees a revolution in digital humanities.

, who sorts through some of the current vibes in Silicon Valley where lots of people apparently think their jobs are about to be obviated, also found Claude Code useful:

The Claudes Code and Cowork are extremely cool and impressive tools, especially to people like me with no real prior coding ability. I had it make me a widget to fetch assets and build posts for Read Max’s regular weekly roundups, a task it completed with astonishingly little friction. Admittedly, the widget will only save me 10 or so minutes of busy work every week, but suddenly, a whole host of accumulated but untouched wouldn’t-that-be-nice-to-have ideas for widgets and apps and pages and features has opened itself up to me.

I wish I could find this reference I came across a few weeks back, but someone I read remarked that Claude Code is a great advance for people who can’t code, but who have a “software shaped hole” in their lives.

That’s what Read has experienced.

We’re still in the stage of being stunned by the novelty of what Claude Code can do.

This has happened every time some leap in the capabilities of LLMs is demonstrated. When ChatGPT arrived, both high school and college English were supposedly ended. When OpenAI trotted out its Sora video generator, Hollywood was some short number of years away from elimination. When AI-generated music started coming, etc, etc…

I find Sinykin’s work very interesting and do not doubt his amazement, and the potential for advancement in the digital humanities is very exciting for people working in the digital humanities, but this is not an epoch shaking change. Max Read’s reaction would be my own, a small jolt of pleasure at making something that saves me a little digital scutwork every week, but this is not transformative at the core of what either of these people do.

As more people explore these applications, they too will find the software shaped holes in their lives, but we have to wonder, how numerous, and how big are those holes? What is the true value of filling them?

Like, I could imagine a Claude Code application that does something I’ve vaguely desired for this newsletter - finding Bookshop.org links for any book mentioned in this column, including in the recommendation request lists of readers. This would be both a minor service to readers, by allowing them to click on the link for more information, and a potential financial benefit to the charities I donate the Bookshop.org referral income to.

Claude Code could fill this hole for me, but it is a very small hole. Only somewhere between 10-15% of the people who access this newsletter ever click on any links period. The additional revenue would be negligible, maybe $50 a year.

We have to get beyond the novelty to fully understand how useful this stuff is going to be, and my bet is that it’s going to be much less transformative in the short term - and Derek Thompson’s two year window is short term - than many seem to believe.

Part of my belief is because I am team . Transformations in the labor force simply take a long time, no matter how powerful or disruptive the technology seems.

I also think that there are fewer “software shaped holes” than many people seem to think, and the software shaped holes that some perceive are not real to those who are in touch with and invested in their work.

This principle was nicely illustrated by an email exchange I had this week with someone who had read More Than Words (or said they had) and was not impressed.

This person wanted to convince me that I really was missing the boat by not using large language models for my writing. Their main argument was “They (LLMs) know more than you ever could.”

I replied that this was not true because LLMs do not have access to the material that goes into my writing, my mind, my experiences, my thoughts, my feelings. It’s not clear to me how someone who had claimed to have read my book had missed these important distinctions, but they were not convinced. This person wanted me to appreciate that I could write “hundreds” of books if I tapped into the power of generative AI. I replied, asking who was going to read these hundreds of books. I haven’t heard back yet.

As it happens, this email arrived just after I’d finished a draft of a proposal for what I’m hoping becomes my next book. I shouldn’t even be talking about it because my agent hasn’t even read it yet, but what the hell, just completing the proposal is meaningful because it was an exercise in proving to myself first that there is a book inside of me, ready to come out.

The introduction to the proposal is a kind of mini-essay ruminating on how, over the course of thirty-plus years I went from a rank incompetent as a writing teacher to someone who now gets paid real US greenbacks to go to places and talk to others about how we should approach teaching writing. One of the roots of how I have become this entirely different person is “experience.”

Here’s what I had to say about that:

“Experience is the best teacher” is one of the cliches that people offer up after you’ve had a lousy experience, an acknowledgement of your pain and suffering and a minor sop towards looking on the bright side because at least you won’t do that stupid thing again, at least not in the exact same way. The reason we don’t immediately punch out the person telling us this is because we know it to be true.

One of the important shifts in my own experience of teaching was when my failures went from humiliations brought about by (literal) inexperience, to failures following good faith, but ultimately ill-conceived or ill-executed attempts at better reaching my students.

I’d crossed the line of agency where I had some measure of intention over my work and my experiences now consistently took the form of intentional experiments. Those experiments often included some element of failure, but these were failures I could work from.

Having sufficient expertise to work from this kind of intention is somewhere down the line of growth, though. At first, you’re going to simply get cuffed around by life, your lack of knowledge, and your inexperience. This can be deeply unpleasant, for example if you forget to completely rinse down a surface that has previously been scrubbed with muriatic acid before applying a soapy cleanser with the nearly opposite pH, resulting in a toxic gas, as happened to me during a brief period of employment as a pool maintenance technician.

In the case of my near poisoning, I’d even been told by Reggie, the crew chief, to make sure to “rinse the shit” out of pool before giving it the wash, but I did not fully appreciate what rinsing the shit out of something meant until I almost killed myself. (Reggie, positioned down wind, laughed and said, “told ya, college” as I scrambled out of the pool and we watched our very minor airborne toxic event waft through north suburban Chicago.)

Similarly, I spent years warning my students about various pitfalls to avoid in the writing of their stories, essays, reports, etc…and yet they would relentlessly commit these sins nonetheless, sometimes minutes after they had been instructed otherwise. I would pull my hair, gnash my teeth, rend my garments and plead with them to pay better attention to my instruction next time, but it never worked.

Why? Because we learn through experience. Not incidentally, the capacity to learn from real world experiences is a hard and permanent difference between human beings and AI. (This generation of AI, at least.)

There is one small part here that particularly tickles me, and is a reminder to myself why writing requires me to just do the work of writing. I’m talking about the parenthetical about Reggie and I watching our “very minor airborne toxic event.”

It tickles me is that I retain these specific memories of Reggie, a guy I worked with for all of six weeks and never talked to again, but who was a genuine character, and that this memory combined in the moment of drafting with a reference to Don DeLillo’s White Noise, a book I would read for the first time in a postmodern literature course the semester after the summer I worked with Reggie.

How amazing is that, that my mind can reach back 35 years and combine these things into a piece of writing that I produced in February of 2026? I could quite easily have prompted an LLM to write a book proposal, to conjure possible chapters, comparative titles, and audience analysis, and it all would’ve been plausible, but it wouldn’t have been mine.

I think Derek Thompson is undervaluing two things. One is the importance of prior experiences to being able to use this technology in genuinely, enduringly useful ways that move beyond novelty. To use these applications productively, we must understand the deep context of our work. It is seductive to believe we can do everything faster, but I think this is a false hope when it comes to both the efficiency and quality of our work.

Interestingly, at least some coders are recognizing similar limitations in outsourcing work to Claude Code, the fact that the outsourcing removes important context that allows them to understand the full picture of what they’re creating. This post from Reddit is deeply thoughtful on this challenge.

One of the byproducts of any automating technology is the erasure of context. GPS erases the work of navigation. Using writing for LLMs erases the experience and unique intelligence behind a text. My work as a writer no doubt biases my thinking, but it’s my view that these contexts are far more important than some would like to believe and that the siren call of increased speed and efficiency may send lots of folks down a false path. I think we’re going to see a lot of visions of transformation that are later to be revealed as mirages as we lurch toward novelty and then have to retreat in order to ground the work in context.

It also has the potential for both labor deskilling and self-alienation. One reason to write my own book proposal is because having done so makes me excited and eager to work on the book. This makes me feel good. It will also help me make a better book. A shortcut to a faster proposal would, in the long run, be a detriment to the final product. I would’ve liked to have this done months ago, and using an LLM to make a simulation of it, I probably could have done so, maybe could have even sold it, but now I’d be sitting here wondering how I’m going to write a book that’s not mine.

Looked at through the lens of life and experience, rather than transaction and output, nothing is immaterial, including those six weeks where you were part of Reggie’s pool cleaning crew.

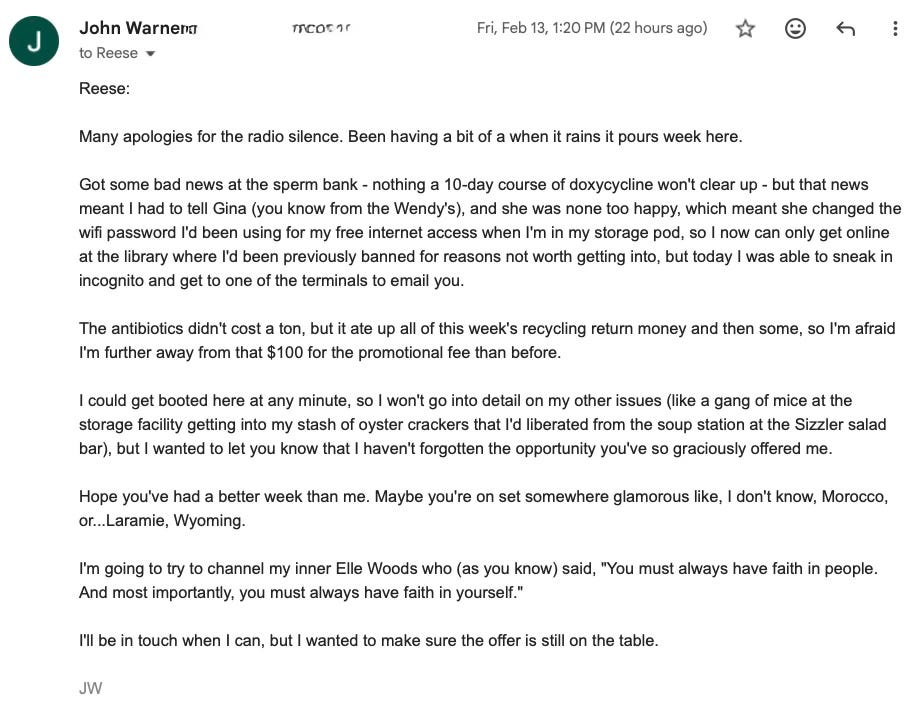

Update on my career-making correspondence with Reese W.

Last week I shared a series of emails with Reese W., who is offering me an opportunity to promote my work.

I didn’t have a lot of time to correspond with Reese W. this past week, but I did want to update her on my efforts to secure the $100 necessary to take advantage of the incredible promotional opportunity.

Reese remains very understanding.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I had the pleasure of describing my pleasure at reading ’s short story collection, Hey You Assholes.

At Inside Higher Ed I rounded up some recent events in higher education that are absolutely, positively, nuts.

After drafting the main text of this newsletter I came across ’s post offering a bet to Scott Alexander that AI technology will be much less disruptive than many think. I’m not smart enough to work through the specific criteria of the bet, but directionally, on this issue, I’m team deBoer.

Another piece I wish I’d read before I drafted the main text, also assessing how big a change that agents like Claude Code may be by looking back at a different software revolution that wasn’t.

Via my friends “Give Us Access to Your Ring Camera and Maybe We’ll Find Your Dog” by Madeline Goetz an Will Lampe

Recommendations

1. Dreaming the Beatles by Rob Sheffield

2. Burn Book by Kara Swisher

3. I Want to Burn this Place Down by Maris Kreizman

4. Lorne by Susan Morrison

5. There’s Always this Year by Hanif Abdurraqib

Michael G. - Royse City, TX

What we got here is a fan of the personal/cultural/memoir-ish essay. I’m having a hard time choosing between two that came to mind so I’m going to break a rule and recommend them both. One is Foreskin’s Lament by Shalom Auslander and the other is Devil in the Details by Jennifer Traig.

Back on the road next week to spread the gospel of treating learning to write as an experience, but I should hopefully have time to maintain my correspondence with Reese W. Let me know in the comments if you any suggestions for what misfortunate may befall me.

Also, what software shaped holes do you have in your lives? I’m curious if my intuition that these gaps are smaller than some think is true.

Thanks, as always for reading, spare a good thought for my book proposal and I’ll see you next week.

JW

The Biblioracle