Grayson Haver Currin’s profile of his friend John Darnielle, founder of the beloved and prolific band the Mountain Goats, plays a bit like a Mountain Goats album. Its ten sections alternate between Darnielle’s nearly 35-year music career and Currin’s 10-day stretch on the road with the band, traveling to Rochester, New York. Each section, like many of Darnielle’s songs, cinches an off-kilter detail, a harrowing backstory, a bit of hard-won heart. (Surely two men holding ten pounds of apples and talking about Geto Boys as they wait for a ride is a scene from some future Darnielle song?) The cast of characters holds big names like Lin-Manuel Miranda and Craig Finn but also makes space for the Pitzer College freshman who, in 1991, turned the PA system back on so Darnielle could sing to six people. “I’d never been so close to something so good,” that student told Currin. It’s hard to imagine getting much closer to Darnielle than this.

He does wonder how long he can write, record, and tour at this pace. In a few months, after all, he’ll turn 59. The list of ailments he’s accrued, whether through life on the road or simply aging, is mounting. This morning, he went to see his doctor again about a retina that’s possibly detaching. (It’s holding steady, thank you.) He is self-conscious about his belly and mentions it often. He laments that, at least at the moment, a string of injuries has kept him from running, a relatively recent enthusiasm. Every time I ran on tour, before I could even catch my breath upon returning to the bus, he would say, “How far did you go? Man, I wish I went with you.”

He tells me more than once he’s looking for an off-ramp, for ways to spend more time at home, hanging out with the kids and writing novels. I remember that in 2006, the first time I interviewed him, he suggested he might stop touring if he had kids. He now gives himself maybe four more years on the road, possibly as many as seven. He loves the work and the people, but he is honest about the indignities of the road, like a 30-hour ride from Maine to North Carolina this summer in a tour bus where the air conditioner died. Wurster remembers that, whenever things would get bad during his early days in the band, Darnielle would joke he was going to jump off the nearest bridge. “Tell them I died taking progressive thrash to new levels,” he would tell his band.

Rose Horowitch, in The Atlantic, says something is deeply wrong with America’s schools:

For the past several years, America has been using its young people as lab rats in a sweeping, if not exactly thought-out, education experiment. Schools across the country have been lowering standards and removing penalties for failure. The results are coming into focus.

Part of the problem, according to Horowitch, is we’re giving away good grades for poor performance in high school classes. But those same signs of academic decay—low standards, reduced penalties—infect all levels of American schooling. The result? Rapidly eroding skills:

The decline started about a decade ago and sharply accelerated during the coronavirus pandemic. The average eighth grader’s math skills, which rose steadily from 1990 to 2013, are now a full school year behind where they were in 2013, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the gold standard for tracking academic achievement.

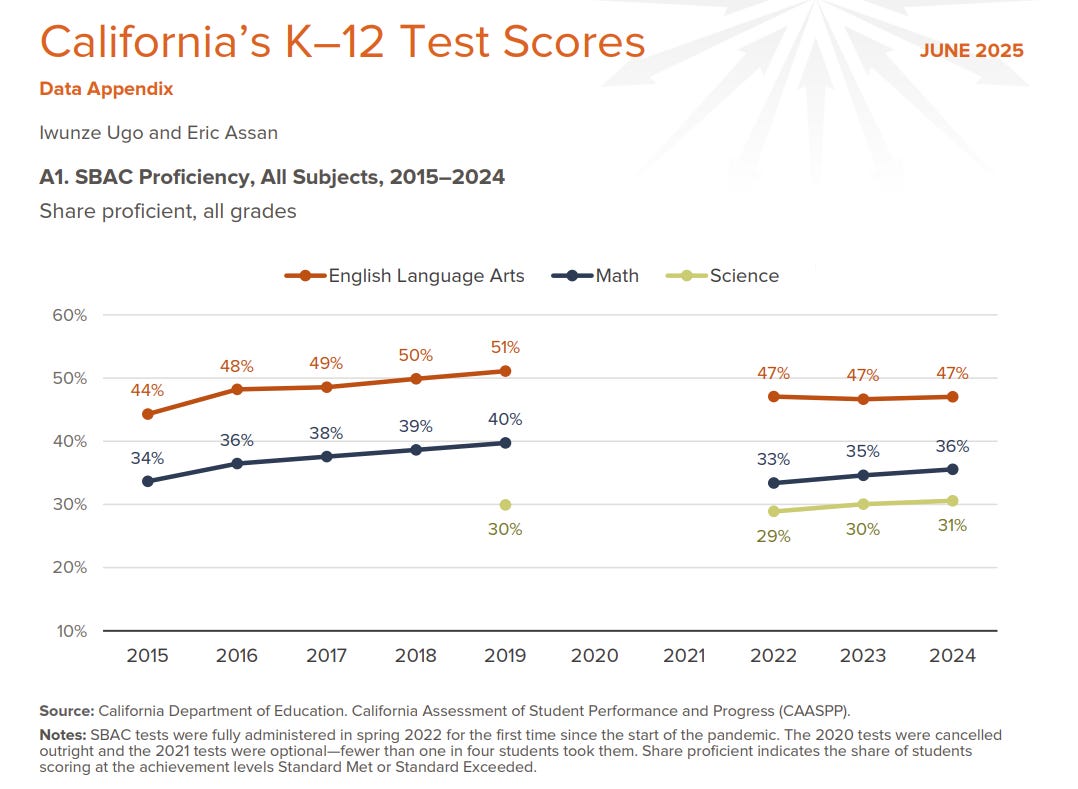

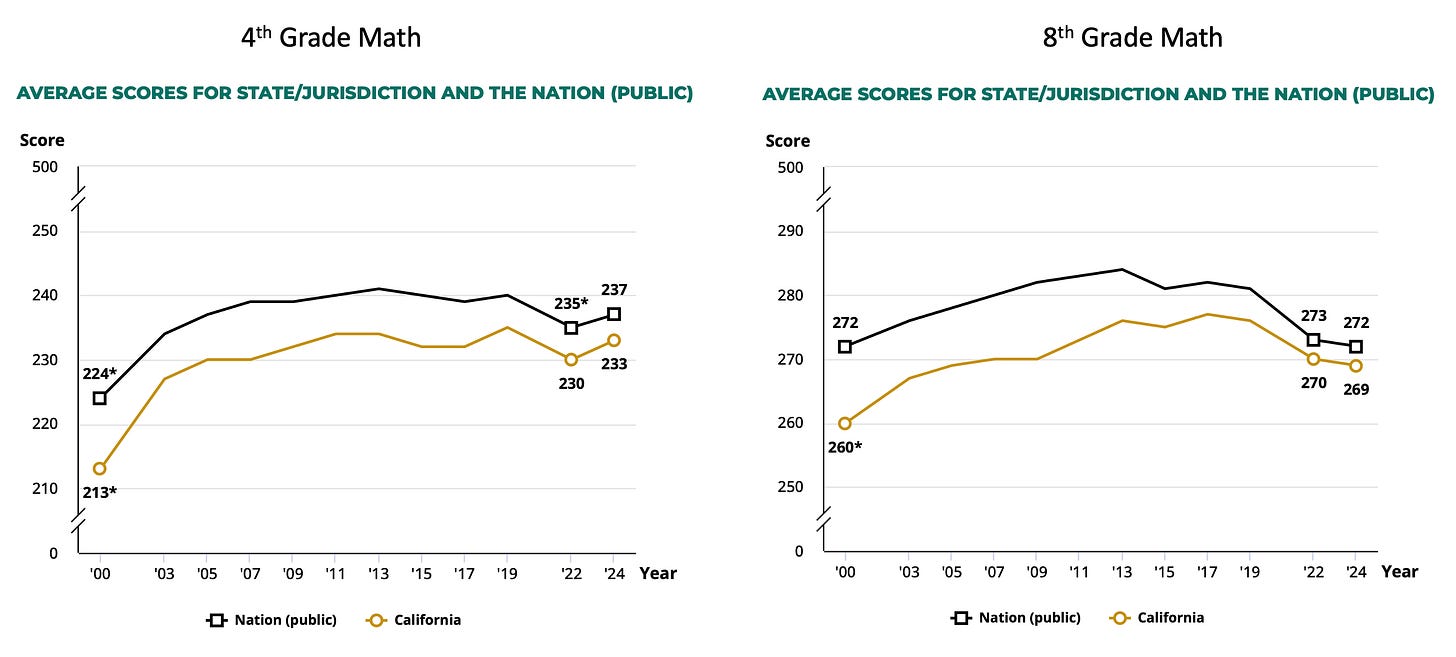

But there’s a problem with Horowitch’s argument. Her piece is anchored by a fascinating report from UC San Diego about their surging remedial math program. She thinks this surge reflects a decline in basic math skills. But there’s no decline on California’s state tests, which instead show increases up until the pandemic (and slow recovery since).

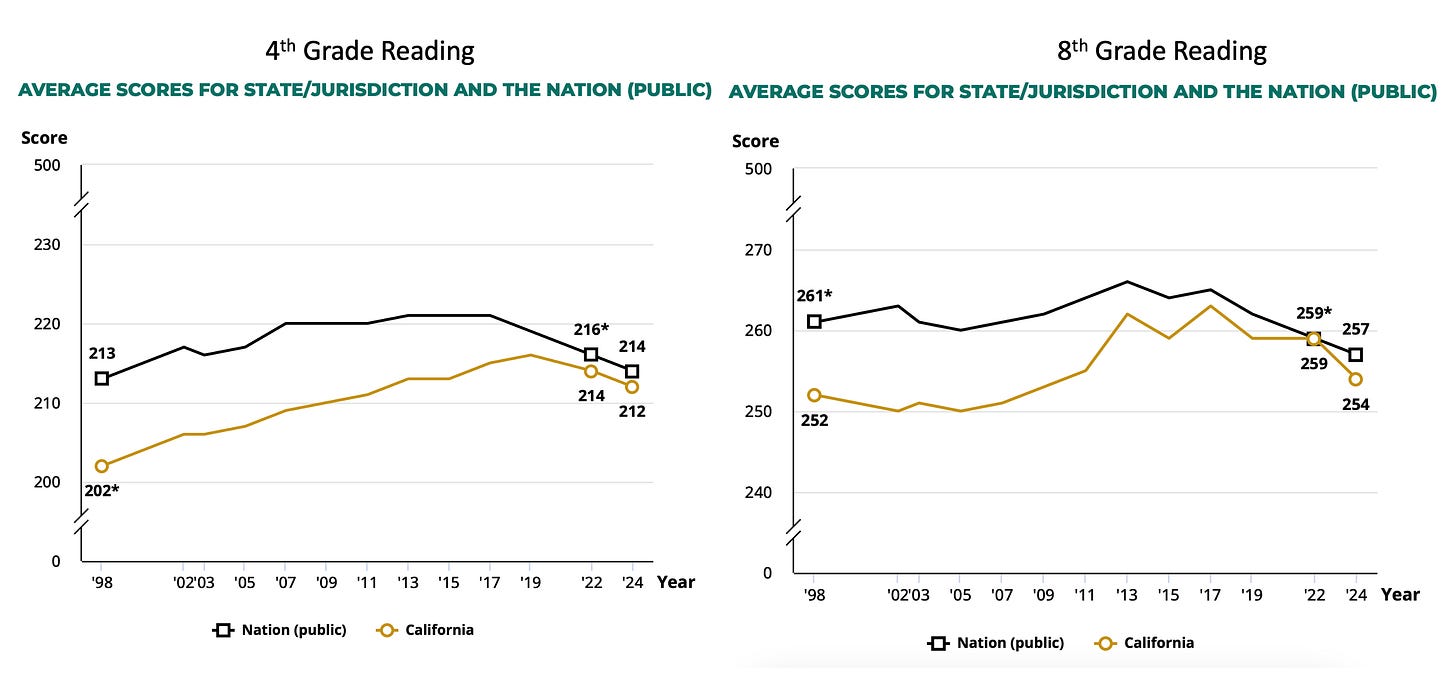

This isn’t to say that Horowich is wrong—test scores have declined in California on NAEP. But when she points to a drop starting in 2013, that could only be in 8th Grade mathematics; 4th Grade math seems to have only dipped in California with the pandemic.

So—were standards only lowered for 8th Graders? And only for math? Because 8th Graders were looking pretty good at reading on NAEP in California until the pandemic.

My point isn’t to defend or focus on California. I’m also not saying that everything is fine. What I am saying is I find all of this very confusing. Some scores definitely started dropping around 2014, but not all of them. I don’t know how you can decide what’s going on in American schools based on these graphs. Whatever the cause of the decline is, it’s not obvious or simple—maybe it’s not even problematic.

It’s Mostly About the Weakest Students

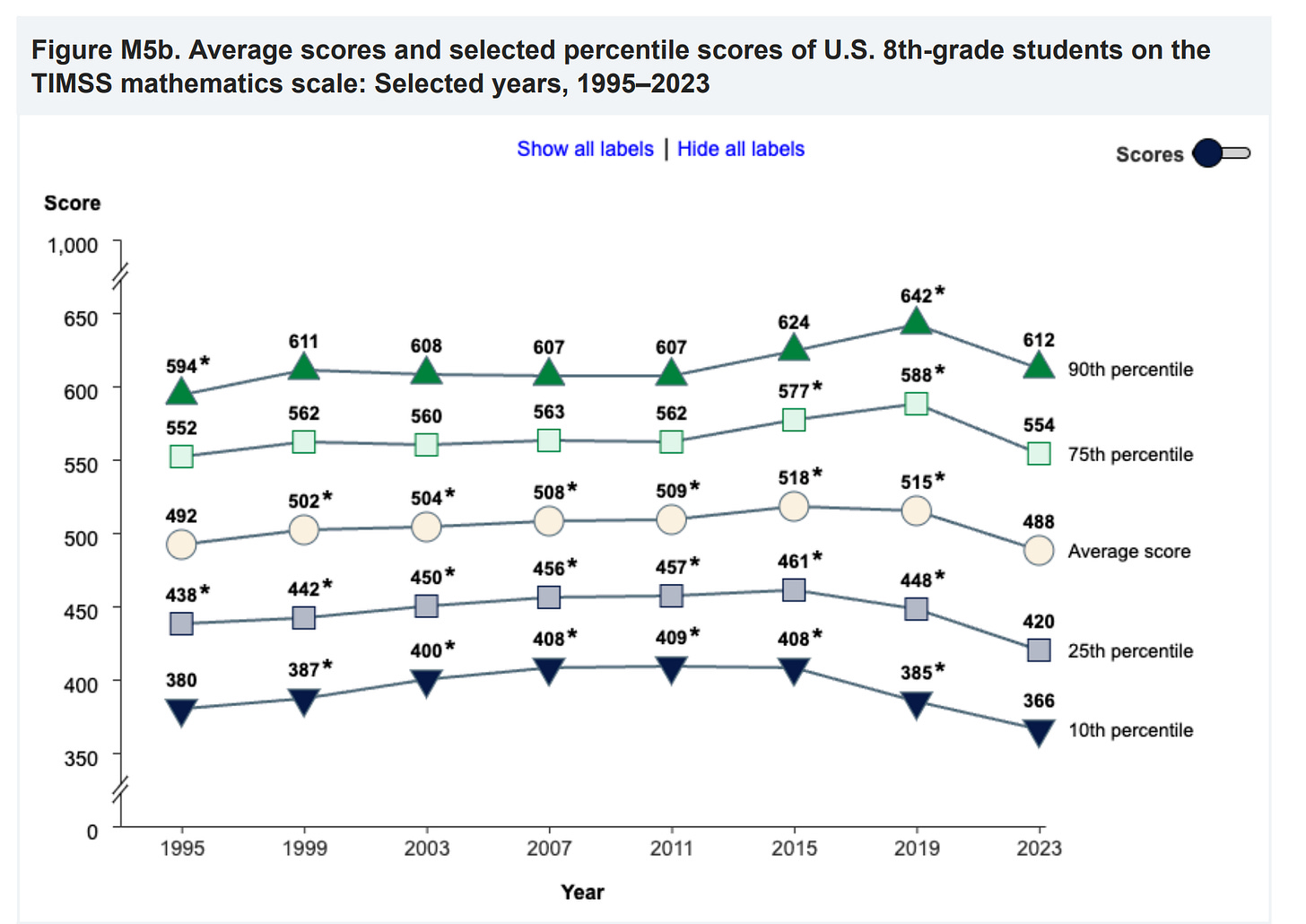

Play around with NAEP scores and you’ll notice that the declines are concentrated in the weakest students. This seems to be the case also for TIMSS, an international assessment. On both the 4th and 8th grade exams, America’s lowest performing students peaked in 2011, while the strongest students continued improving through 2019.

So are American students “getting dumber,” as Matt Yglesias says?

First, that’s rude. But second—no, they aren’t! I mean, yes, even high fliers were impacted by the pandemic. Everyone was. But strong students were looking fine up until then. That cuts out some possible explanations: this isn’t about detracking, gifted education, grading in AP classes, or anything else that would primarily impact the strongest 10% of students.

So…is it test-based accountability? Economist Joshua Goodman thinks so. He points out that 2015 is when the Obama administration started issuing waivers that defanged No Child Left Behind. Up until then, high-stakes testing pushed schools to focus on lifting weaker students up.

Listen—I don’t know! I’d quibble that since NCLB was introduced in 2001, it can’t explain the decade of improvements leading up to that law. And because NCLB was focused on math and reading it can’t explain declines in civics or US history.1

But there’s another, more significant problem with this explanation…

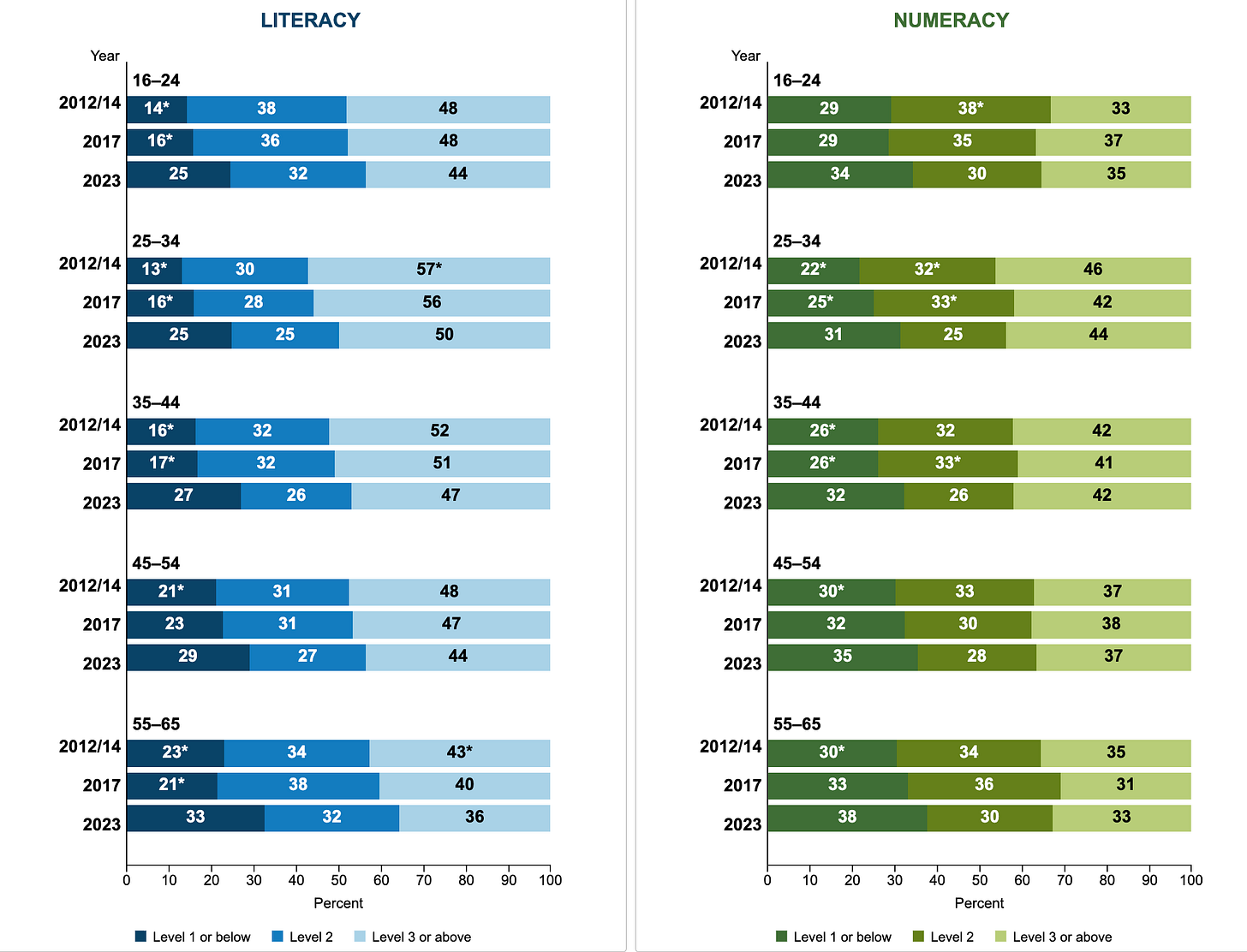

It’s Not Just Kids

Chad Aldeman has been writing about declining test scores for years, and generally favors an explanation not unlike Goodman or Horowich’s. But it was from him I first learned that American scores on PIAAC, a test of workplace skills for adults of ages 16 to 65, have also been on the decline, arguably also peaking around 2014.

There were declines in every cohort, in both literacy and numeracy, even in the 55-65 group that has been out of school for over forty years.

Isn’t that…deeply weird? So it’s not just kids that have lost progress, but adults. How could schools possibly be responsible for that? And not all countries experienced a decline. So something is going on in America that impacted both students and adults beginning in 2014. What could it be?

It’s Not Just Phones, and it’s Not Just Here

Adults have phones. Teens have phones. Maybe it’s phones?

Goodman thinks this is part of the story. Horowich mentions this too. But as Aldeman points out, phones are everywhere and declines in TIMSS scores aren’t universal:

Smartphones and social media are global phenomena, and yet scores in Australia, England, Italy, Japan and Sweden have all risen over the last decade. A couple of other countries have seen some small declines (like Finland and Denmark), but no one has else seen declines like we’ve had here in the States.

(I’d also point out that 4th Graders typically don’t have phones, so they couldn’t explain declines in 4th Grade NAEP reading.)

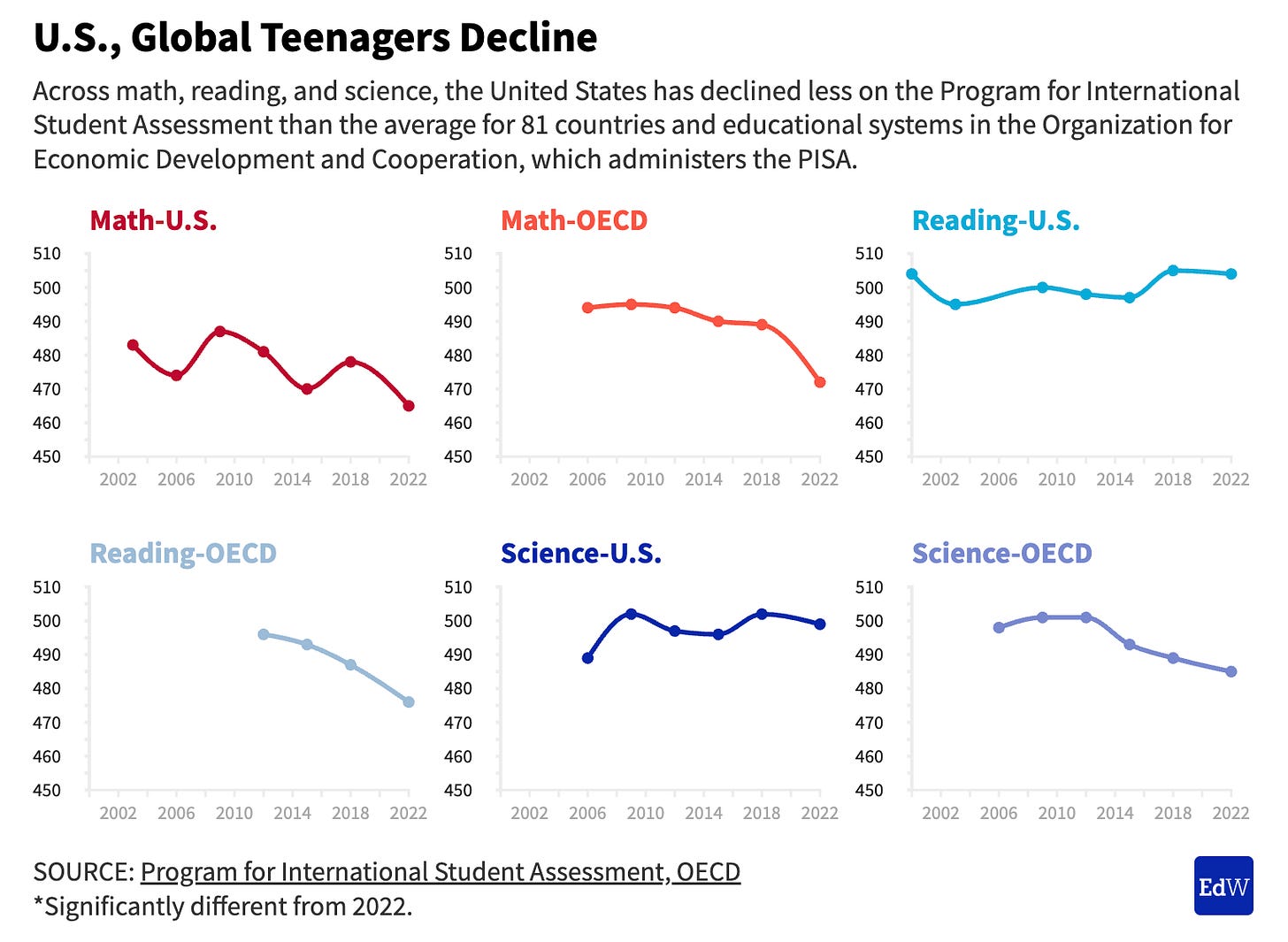

But on the subject of international declines, and whether America is an outlier, there is another major international exam besides TIMSS—that’s PISA. And PISA scores have been down across the board since around 2014.

Weirdly, looking at this graph, America looks like it’s beating these trends in reading and science. How do you explain that? Why would countries participating in PISA have overall declines starting midway through the decade when TIMSS did not? Why would the US partly buck the trend on PISA, the test we traditionally do worse at, and then underperform the international trend on TIMSS, the exam we do much better on?

Now, there are differences between TIMSS and PISA. TIMSS is generally more of an achievement test with questions that closely resemble what students learn in school. PISA is designed to go a step further, requiring interpretation and application. Maybe that explains the different international trends…

But at this point, I want to throw my hands up—I just don’t know what’s going on!

So, what is it?

Here’s the situation: Americans are getting dumber...well, mostly not. But our lowest performing students seem to be losing ground. And, simultaneously, our adults. Some international tests show a similar decline happening in other countries. On other exams, America is on its own. What gives?

For a moment I had a theory that I liked—that it’s about the shift from paper to digital assessments. NAEP went digital in 2017. PISA went digital in 2015. TIMSS transitioned in 2019. Kids do a lot of lazy button pushing when they take these digital exams.

Maybe the issue is giving tests with the same devices we use to scroll YouTube?

This is definitely something to worry about (it’s a “mode effect”) but it seems as if the test-makers are on top of this. I guess I trust them not to mess up? Also, you’d figure that if there was a big problematic mode effect it would be more of a one-time hit. It probably wouldn’t cause a steady decline…right?

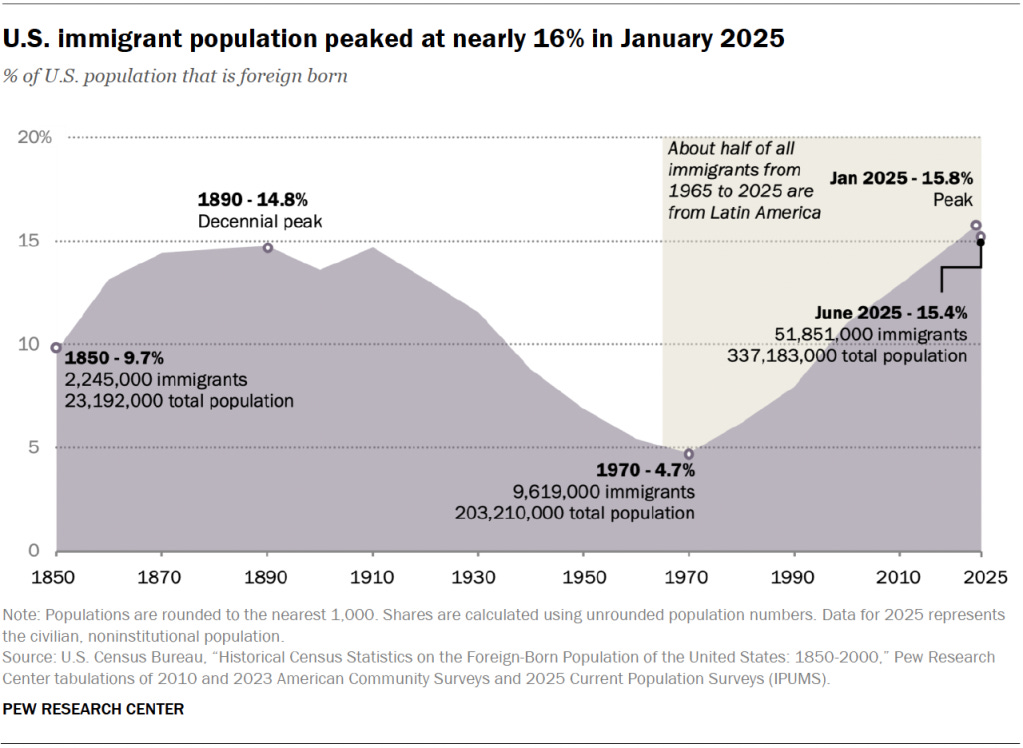

OK, another theory: is it just a coincidence that this tumult coincides with a huge influx of immigrants to the United States? Wouldn’t that change the adult workforce along with the school population? Demographic shift is the most accurate answer to so many educational questions—could it help us here?

I don’t know! This is all so speculative. I feel like I’m just making things up. And none of the explanations are completely satisfying.

Meanwhile the amount of confidence on display from our political writers is remarkable. They seem quite sure that American schools are in crisis, that students aren’t being taught, that there is some grand trick being played on the American public.

But the facts are confusing. So why the confidence?

“America has been using its young people as lab rats in a sweeping, if not exactly thought-out, education experiment,” Horowitch writes, and would it be crazy to say that she sounds a little bit jealous?

The American school system is stubborn. It evolves slowly and only in complicated ways in response to the demands of outsiders. It’s hard to reach into classrooms. Maybe that’s the point here. Writers, advocates, policymakers—many of them love the idea that schools have been steered in the wrong direction. After all, that means they can be steered, and maybe you can even take back the wheel. Climb aboard, everyone! We’re headed back to the 2000s.

TIMSS also measures science achievement and those declines were less severe for the US. NAEP declines are also less steep for science. Under NCLB, schools allocated more time and resources for math/reading at the expense of subjects like science and history. Maybe those less intense declines support the NCLB theory.

Abstractions are powerful tools. Given enough abstraction everything gets somewhat simple. Somewhat clear. Also somewhat wrong. Abstraction turns everything real, material, consequential into mostly nothing. The abstraction of “a relationship” hides all the love and care and desire it might entail. The abstraction of “the border” hides the violence its defense entails.

Given enough abstraction every monstrosity becomes just a kind of mental gymnastics. This is the domain of devil’s advocates kind of people form whom the real often political meaning of certain statements or movements has become fully replaced by a game of debate. Who cares about the position, let’s win!

I keep thinking about abstractions when looking at the state of the current “AI” bubble and with it the state of a lot of the global economy.

As most people reading this know, I am not a fan of “AI”. If I never have to hear or read or see the term “agentic” ever again that would still be too early. Not only do I despise the political project that is “AI”, the mental damage these systems do to us, the harm to the environment they create, etc. but the way the narrative has turned a narrowly useful technology (stochastic pattern generation and recognition using neural networks) into the hammer to demolish all established codes and practices that ensure some base level of quality: But hey, who wants their software be developed by a team of professionals who can actually understand, model and solve or mitigate security issues when you can also just use a slot machine?

I’ve found myself saying how much I’d love the “AI” bubble to pop if just to shut “AI” influencers up, if just to have some space to talk about real solutions to real problems again. But that only works in abstraction. Only works when nothing means too much, really.

For worse (there’s no better in this sentence) we have made “AI” the foundation of many core parts of our economy. Not “AI” systems – those don’t really work, or meaningfully increase productivity – but the belief in the (future) value of the handful of tech companies building these systems. The US would be in a recession without the data center buildout that tech is throwing all its savings at. A buildout that is not connected to any form of successful business yet. “AI” does not scale the way digital services usually scale but all we see currently is still the old “increase user numbers and hope a business plan will manifest itself” scheme. Maybe ChatGPT can give Sam Altman some form of strategy besides lying.

This has material consequences. When (not if) the bubble pops we will see a few things: The stock market will take a dive which will affect many people living in countries without pension systems who rely on the money they have invested in ETFs or stocks. I am not talking about some VC dude or millionaire losing a few millions or billions, just normal people who wanted to retire at some point. Companies who have bet on “AI” now no longer can claim that one “needs to get onboard” and ride the hype but will have to fix their budgets – quick. This will lead to squeezing employees even more, firing people to make the next quarter’s numbers look better. In the current political landscape the instability that right leaning tech oligarchs and their fans will have created will probably benefit the right. We’ll see a lot of blame going around (remember: “AI” can never fail us, we can only fail “AI”. If this thing crashes, we did not believe enough!) and cuts to social services and anything that gives people the feeling of living in a functioning society. Which only helps right wingers but well that’s Neoliberalism for you.

I love the abstraction of the “AI” bubble popping. But the very probably effects haunt me.

This shouldn’t be read as a “well, ‘AI’ is here to stay so let’s make the best of it” kind of thing. I neither think “AI” will automatically stay (again: see this) nor am I sedated enough to believe that political values and action have no meaning. While I think there are a few narrow use cases for machine learning, whatever is called “AI” today has very few redeeming qualities being built on extraction, violence, domination, colonialism and right wing, anti-labor politics. This is not a moment of capitulation but of reflection.

It’s always easy to cheer for a revolution. Shit is fucked up and bullshit and our institutions and structures don’t seem to be willing, capable or motivated to meaningfully move towards a better world so let’s fuck shit up! Burn down data centers. Get out some guillotines. The thing is: Revolutions mean that people get hurt. That ultimately people die. That doesn’t mean that revolutions are always wrong, but it means that the abstraction is again doing a lot of work hiding harm to people who just want to get through their workday to be home with their family.

My criticism of “AI” is about limiting injustice and suffering. The suffering of the communities who get data centers put in their midst drinking up all the water, taking the electricity while producing metric fucktons of emissions, e-waste and noise. The injustice done to kids who get to chat to an LLM instead of building meaningful relationships to teachers and mentors, who don’t get to figure out what they are good at cause everything they do looks worse than “AI” output so they use that instead of getting to be so much better than slop machines. The way that non-working stochastic parrots undermine labor power and therefore putting the livelihood of thousands of families at risk. My criticism comes from love and care for people, communities and societies. So my actions can’t abstract the effects of those away.

But what can be done? In a better world we’d see governments segmenting the toxic “AI” part of the economy off and insulating the actual economy against it. Slowly moving big public investments out of those companies (not the best word, they seem more like cults these days but we still call them companies). Preparing for that bubble to deflate without taking thousands of lives with it. But we see the opposite: Europe where I live keeps wanting to throw all the money they can find at more “AI”. Just do more “AI”, it will be so good, bro. Trust us, bro. Just 10 more billion. It’ll be super cool, bro. Governments treat hyped tech like a stoner threats hits of their bong.

So what can we do? That is the question. Moving our savings out of the stock market? Maybe – if you have some. Stopping to criticize “AI” systems and the narratives that push them? Never: We mustn’t prop up or protect those dangerous and harmful systems by inaction.

I don’t have all the answers (I rarely have any TBH) but I do think that we should be at least careful wit glorifying the bubble popping a bit. Sure it’s fun to predict when it will go down and how much money Softbank is gonna set on fire but I think that it is also our job as critics to make sure that the public understands that “the AI bubble popping” has material consequences for them. That joining a union might be a good idea right now. That getting smart and knowledgeable people on Works councils is more important than ever. That tech companies are not your friends or benevolent and that they’d sell your kids if it made the stock perform well.

The “AI” bubble will deflate. But as cathartic as a “POP” might feel right now, we need to build the structures that ensure that this event doesn’t put a lot of harm on people who had nothing to do with it. Let Marc Andreessen or Satya Nadella or Sundar Pitchai and all those tech bros lose their money, make sure that after the storm nobody forgets that these people gambled with our lives and societies to make number go up. But we can’t just focus on holding those men accountable – as righteous and good that might feel (and holy cow do I want to see many of those people put on trial). We need to start building lifeboats and barriers protecting our peers, neighbors, families and communities.

We are all we have. Only solidarity will get us through this.

Paul McCartney is releasing a new track. It’s his first new song in five years—so that’s a big deal. But there’s something even more significant about this 2 minute 45 second release.

The song is silent. It’s a totally blank track—except for a bit of hiss and background noise.

What’s going on? Has Paul McCartney run out of melodies at age 83? Is he nurturing his inner John Cage. Did he simply forget to turn on the mic?

No, none of the above.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

Macca is releasing this track as a protest against AI.

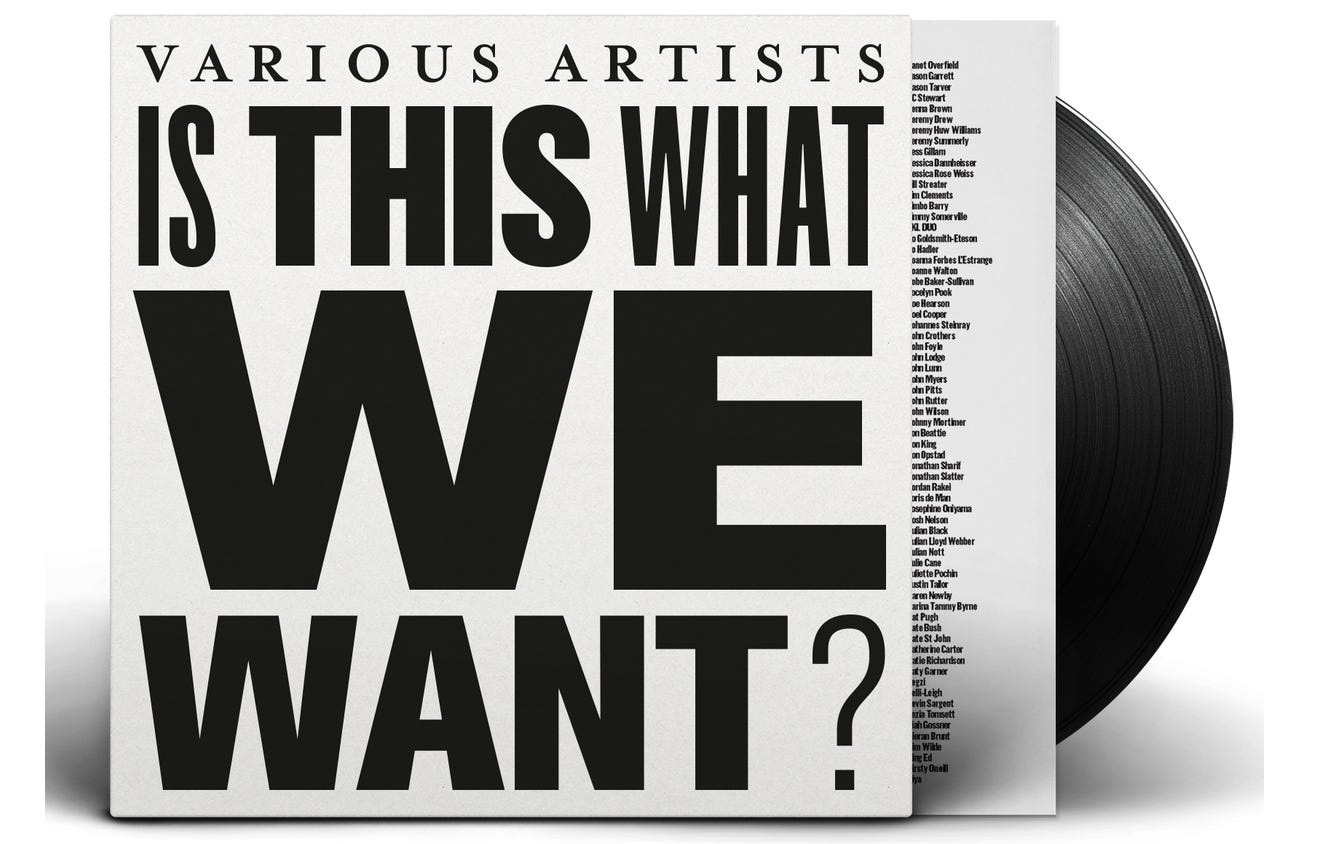

His new ‘music’ is part of an album entitled Is This What We Want? It’s already available on digital platforms, and is now coming out on vinyl. All proceeds will go to the non-profit organization Help Musicians.

“The album consists of recordings of empty studios and performance spaces,” according to the website. In addition to McCartney, more than a thousand musicians are participating, including:

Kate Bush, Annie Lennox, Damon Albarn, Billy Ocean, Ed O’Brien, Dan Smith, The Clash, Mystery Jets, Jamiroquai, Imogen Heap, Yusuf / Cat Stevens, Riz Ahmed, Tori Amos, Hans Zimmer, James MacMillan, Max Richter, John Rutter, The Kanneh-Masons, The King’s Singers, The Sixteen, Roderick Williams, Sarah Connolly, Nicky Spence, Ian Bostridge, and many more.

I keep hearing that protest music is dead—and has been losing momentum since the Vietnam War. But there’s now a new war, and it’s stirring up creators in every artistic idiom.

They are fighting for their livelihoods and IP rights. And, so far, it’s been a losing battle.

You can see the new battle lines across the entire creative landscape.

Vince Gilligan, one of the most brilliant minds in TV, admits that he “hates AI.” He calls it the “world’s most expensive plagiarism machine.” For his new show Pluribus, he has added this disclaimer to the credits:

This show was made by humans.

AI represents the exact opposite of creativity, Gilligan warns. It steals the work of others. So any attempt to legitimize it as a creative tool is built on lies. A bank robber might just as well pretend to be a financier. Or an art forger claim to be Picasso.

Filmmakers are reaching the same conclusion.

Oscar-winning director Guillermo del Toro says he would “rather die” than use AI in his movies. You might even view his latest film Frankenstein as a pointed attack on technology gone wild. He describes Dr. Frankenstein as

similar in some ways to the tech bros. He’s kind of blind, creating something without considering the consequences.

But here’s where things start to get really creepy. The headline above comes from Variety, a leading voice for the entertainment industry. But the new publisher for Variety is a huge fan of AI—and sees it as essential to the future of the periodical.

It’s worth noting that this publisher started her career at Variety by selling ads, not writing. And that gives you a clear sense of the people on the other side of the battle field.

The people who have built careers on their creativity are now mobilizing. But the overseers who prioritize finance and profits will fight them at every turn. You might think that these two parties need each other—but that’s not how the bosses see it.

They love AI because it will reduce their dependence on human artists—who are often stubborn difficult people. Even worse, great artists are expensive people, so the suits inside the boardroom dream of replacing them with servile bots.

Very few of the bosses will say this openly. They can’t afford to stir up their creative workers—not yet. It’s too early and AI tech isn’t robust enough to replace all those folks in the cast and crew. But if you don’t think this is the plan, you don’t know how the people in those expensive boardroom chairs think and act.

Just take a look at the new AI “talent studio” Xicoa. A few weeks ago, it introduced an AI actress named Tilly Norwood. She’s a sweet brunette who looks like the girl next door—provided that you live inside a simulation.

The creative community was disgusted by this. But movie studios and agents reached out to the company, eager to explore ways of working together. In the aftermath, Xicoa announced that it is developing another 40 AI-generated actors.

According to one inside source, all the studios and major film companies are looking at AI projects. But everything is top secret, wrapped up in non-disclosure agreements—so we can only guess at the details. But the threat is clearly escalating at a rapid pace.

We see the exact same thing in music. Big records labels complained about AI—until they got a cut of the action.

So Warner Bros had a strong copyright infringement case against an AI music company—but then decided to reach a settlement.

Universal Music did the exact same thing.

Sony is also cutting AI music deals.

I believe that the music industry could put AI companies out of business—the robbery of IP is so severe that this could be Napster all over again. Flesh-and-blood musicians would be protected, and real creativity could flourish.

But the bosses don’t want that. They will sell out the musicians—just so long as they make some money in the transaction.

And the exact same thing is happening in publishing.

Let me repeat: AI companies could be stopped simply by prosecuting them for violating copyrights. Why isn’t this happening?

Who wants to hear a bot sing of love it has never experienced? Who wants a painting made by something with no eyes to see?

The answer is simple—and sad.

Instead of protecting artist rights, the big companies in the culture sphere are seeking collaboration and quick settlements. Creators absolutely need to understand this. It’s not clear that they can trust their own labels or publishers—or maybe not even their own lawyers.

This is the new culture war.

And it’s very different from the old culture war—which was a dim reflection of politics. This new battle is happening inside the culture world itself, and threatens to cut off artists from their own longstanding partners and support systems.

This new culture war will only escalate. The stakes are too high, and artists can’t afford to stay on the sidelines. But they face heavy odds, with the richest people on the planet opposed to their efforts.

How will this battle get decided? It really comes down to the audience. If they prefer AI slop, we will witness the total degradation of arts and entertainment.

I’d like to think that people are too smart to fall for this crude simulation of human creative expression. Who wants to hear a bot sing of love it has never experienced? Who wants a nature poem from a digital construct that exists outside of nature? Who wants a painting made by something with no eyes to see?

Will the public find this charming. Or even plausible? Maybe a few twelve year olds and fools, but not serious people. That’s my hunch.

In any event, we will soon find out.