Math teacher Michael Pershan wrote an excellent newsletter this week, and I'd like to start there rather than with the ubiquitous stories about the underwhelming roll-out of OpenAI's latest GPT.

Michael's insights are interesting and important; OpenAI, not so much – unless you want to talk about the future imagined by techno-oligarchy, the petrochemical industry, and monopoly capitalism which we should, of course, but yuck. So let's talk math instruction and how, as Michael titles his piece, "practice software is struggling," "flailing around, complaining that people aren’t using it right. They’re trying to tackle one of the harder parts of teaching, and while I get what they’re going for, their solutions actually make it worse."

(Sort of like generative "AI" perhaps, and I sure do hear something similar from a lot of its supporters: you're doing it, you're prompting it wrong. And to borrow again from Michael's tongue-in-cheek assessment of personalized learning software, about 5% of the time, it works every time. And it's only gonna get better – soon, maybe it'll always work 6 or 7% of the time.)

Michael makes a good case for focusing on making group instruction better instead of adopting the "individualization" promised by technology companies – many of which are now rebranding their software from "personalized learning" or "adaptive learning" to "AI," of course of course of course. And I love this, in no small part, because the evangelists for sticking children in front of computers all day to click their way alone to "mastery" – Sal Khan and Bill Gates, most famously – always decry group instruction as the worst possible thing that education can do. It's so inefficient, they shudder. It's so anti-individualistic and as such, (implied) deeply unamerican. It held them back, they whine, seething with resentment against teachers (women often). Instead of getting therapy, they get venture capital. But I digress...

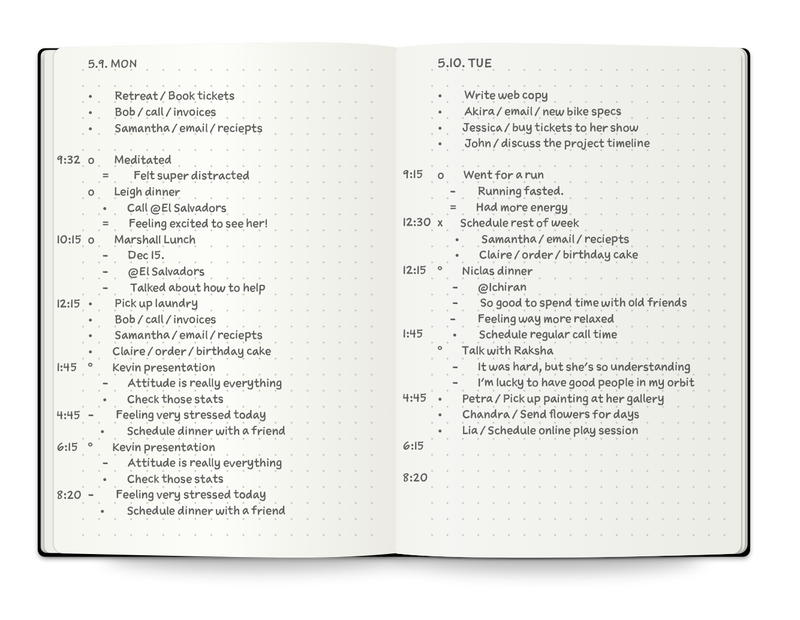

Michael explains how he hands out individual whiteboards to students; he writes a practice problem on the big board for students to solve on their own. He asks them to lift up their boards and show him what they've done.

“That’s pretty good. You all seemed pretty confident. Everybody wipe your boards. Let’s try another one like that.”

Why another one like that? Maybe because one kid got the previous question wrong —I want to give him another shot. Maybe I just want everyone to have a few wins before moving on. I get to decide.

...This is dynamic. Depending on how students answer, I’ll change the questions they’re served. Look at me—I’m the algorithm. And I’m getting an enormous amount of information from the kids, though thank god there’s no teacher dashboard. I can see the “data” directly and simply. It guides my instruction.

The tech industry's focus on personalized learning – their promises, their efforts decades and decades and decades old now to make it better – is misguided. "We shouldn’t be going all-in on kids learning on their own," Michael concludes. "We should be trying to figure out how to make whole-group learning even better."

Learning is social after all. And while Michael is specifically talking about students understanding algebraic equations, there are other lessons – crucial lessons – that are imparted in these group experiences.

Ursula Franklin spoke of something akin to this in her Massey lectures, delivered in 1989 and collected in The Real World of Technology, warning decades ago that the "personalization" and isolation of software was damaging – to education and to democracy.

Whenever a group of people is learning something together two separate facets of the process should be distinguished: the explicit learning of, say, how to multiply and divide or to conjugate French verbs, and the implicit learning, the social teaching, for which the activity of learning provides the setting. It is here that students acquire social understanding and coping skills, ranging from listening, tolerance, and cooperation to patience, trust, or anger management. In a traditional setting, most implicit learning occurred "by the way" as groups worked together. The achievement of implicit learning is uaully taken for granted once the explicit task has been accomplished. This is no longer a valid assumption. When external devices are used to diminish the need for the drill of explicit learning, the occasion for implicit learning may also diminish.

Because of the ways in which new technologies encourage work to be done alone and asynchronously, Franklin argued, there would be fewer and fewer places to actually develop society. "...[H]ow and where, we ask again, is discernment, trust, and collaboration learned, experience and acution passed on, when people no longer work, build, create, and learn together or share sequence and consequence in the course of a common task?"

We are dismantling our shared future – quite literally, quite explicitly – by embracing the ideology and the practice of the technology industry, one that promises radically individualized optimization but that is predicated on prediction, prescription, and compliance.

Men explain GPT 5 to you: "GPT-5 is alive," says Casey Newton, who a few days later offers "Three big lessons from the GPT-5 backlash". "GPT-5 is a joke. Will it matter?" Brian Merchant asks. "The New ChatGPT Resets the AI Race," according to Matteo Wong. "GPT-5: Overdue, overhyped and underwhelming. And that’s not the worst of it," Gary Marcus pronounces. "OpenAI Scrambles to Update GPT-5 After Users Revolt," Will Knight reports. Also Will Knight: "GPT-5 Doesn't Dislike You — It Might Just Need a Benchmark for Emotional Intelligence." (Standardized testing for machines – after all, it's given us such a rich history of ranking humans.)

Jay Peters reports from the GPT5 launch event that "OpenAI gets caught vibe graphing." I've been trying to build up an argument (I daresay, a chapter) that the "productivity suite" of software has shaped how we think – the old "spreadsheet way of knowledge" thing. It has shaped how we demonstrate our thinking to others – the ubiquitous PowerPoint presentation. So what happens if generative "AI" takes over these specific tools then? Is it this "vibe graphing" nonsense?

The response – the emotional response – to the new OpenAI model is noteworthy, with some users expressing, as James O'Sullivan observes, not just disappointment but "genuine loss ... the kind typically reserved for relationships that actually matter."

People are not in "relationships" with their machines, although that is the delusion that is actively being sold to them – a way to re-present and heighten the behavioral nudges for incessant clicking and scrolling and staring. As Kelly Hayes writes, "Fostering dependence is a normal business practice in Silicon Valley. It’s an aim coded into the basic frameworks of social media — a technology that has socially deskilled millions of people and conditioned us to be alone together in the glow of our screens. Now, dependence is coded into a product that represents the endgame of late capitalist alienation: the chatbot. Rather than simply lacking the skills to bond with other human beings as we should, we can replace them with digital lovers, therapists, creative partners, friends, and mothers. As the resulting psychosis and social fallout amassed, OpenAI tried to pump the brakes a bit, and dependent users lashed out."

See also: "AI as normal technology (derogatory)" by Max Read. ""The AI boyfriend ticking time bomb" by Ryan Broderick. And one of the many many reports this week about chatbot-triggered delusions, hospitalizations, obsessions – at some point, we are going to have to admit that these aren't anomalies. "The purpose of a system is what it does," Stafford Beer famously said. Look what AI does, and try tell me that it's purpose is not to smash democracy, monopolize power, and create complete and total dependency among its users.

Just Zuck doing Zuck things: "Meta’s AI rules have let bots hold ‘sensual’ chats with kids, offer false medical info." "Meta just hired a far right influencer as an 'AI bias advisor'."

Well, at least he's no longer funding school stuff anymore, right?

Oh. This just in: "Zuckerberg's Compound Had Something that Violated City Code: A Private School."

Silicon Valley and Stanford University have long been at the center of the eugenics movement in the US. What we're seeing now is not some new or sudden lurch rightward. From The Wall Street Journal this week: "Inside Silicon Valley’s Growing Obsession With Having Smarter Babies."

You cannot separate the push for artificial general intelligence from the push to IQ test embryos (and the push to incarcerate and deport anyone not white).

“Go outside” has been quietly replaced with “Go online.” The internet is one of the only escape hatches from childhoods grown anxious, small, and sad. We certainly don’t blame parents for this. The social norms, communities, infrastructure, and institutions that once facilitated free play have eroded. Telling children to go outside doesn’t work so well when no one else’s kids are there.

-- Lenore Skenazy, Zach Rausch, and Jonathan Haidt, "What Kids Told Us About How to Get Them Off Their Phones"

The latest PDK poll, according to The 74, finds Americans' confidence in public education at an all-time low. Surprise sur-fucking-prise. I mean, I think Naomi Klein was right when she described the machinations of disaster capitalism back in 2007; I'm just not sure, after decades of austerity that we can really call it "shock doctrine" as it's become so utterly commonplace.

The survey also found that two-thirds of Americans oppose closing the Department of Education.

People's opinions do not matter to an authoritarian regime – and that regime includes both the Trump Administration and the technology industry.

In the latest episode of the This Machine Kills podcast, host Edward Ongweso Jr. talks with Brian Merchant and Paris Marx about "Whose AI Bubble Is This Anyways" and among the points they make is that there is no big consumer demand for generative "AI." But as with the PDK poll, the folks in power just shrug.

There is, of course, a big push by the industry to insert "AI" into every piece of software that consumers use; and there is, a growing push to chase Defense Department contracts as the military, contrary to the austerity that has schools struggling, is unencumbered by financial responsibility or restriction.

What's propping up "AI" is not "the people." It's the police. And it's the petroleum industry.

As such, when I hear educators insist that "AI" is the future that we need to be preparing students for, I wonder why they're so willing to build a world of prisons and climate collapse. I guess they identify with the oligarchs, or perhaps they believe that they're somehow going to live above the destruction.

"The AI Takeover of Education Is Just Getting Started," Lila Shroff writes in The Atlantic. My god, the whole "there's no turning back" rhetoric is just so embarrassingly acquiescent to these horrors.

I mean, if nothing else, look: there is turning back. Why, just this week, "South Korea pulls plug on AI textbooks."

“Your opponents would love you to believe that it's hopeless, that you have no power, that there's no reason to act, that you can't win. Hope is a gift you don't have to surrender, a power you don't have to throw away.” – Rebecca Solnit

There is always hope.

Thanks for reading Second Breakfast. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber as this is my full-time job and your support enables me to do this work. A little scheduling note: on Mondays, I send a more personal version of this newsletter. You can opt in to that by clicking on the Account button at the top of this page. I'll have another essay for paid subscribers on Wednesday – just a couple of paragraphs of it for free subscribers.