This post first appeared on Marcus on AI, and is reposted with the permission of the author.

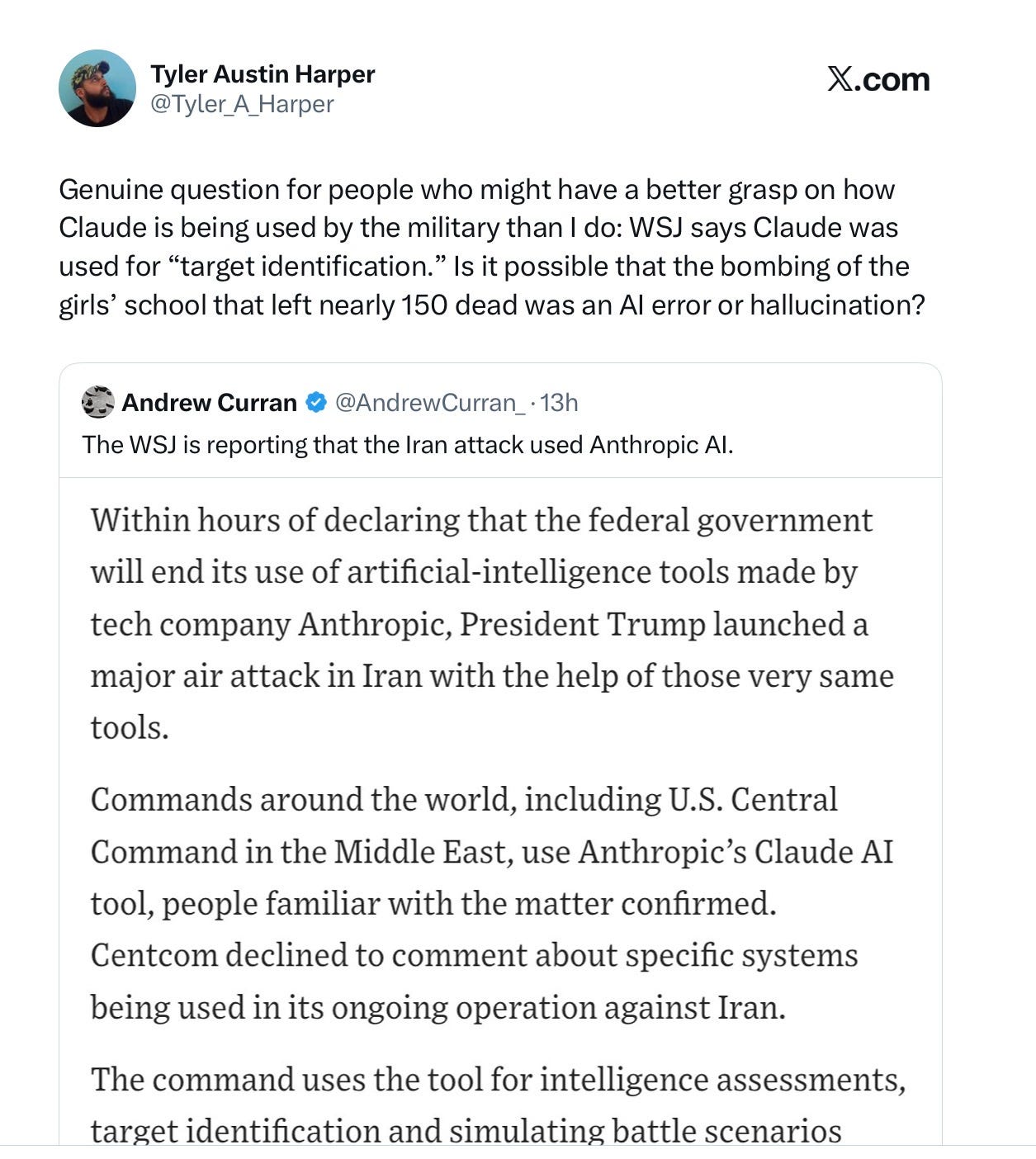

The writer Tyler Austin Harper (of The Atlantic, etc.) sent me a thread this morning, asking whether a mistargeting yesterday (February 28) that killed nearly 150 school children in Iran could have been the result of AI.

I can give only two intellectually honest answers:

The first is: I have no idea what happened yesterday, and probably I will never know. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has made a very heavy bet on AI in the military, and it’s doubtful that he will be entirely forthcoming about this or other incidents to come. Targeting errors aren’t new. We may get little detail about AI’s role or non-role in incidents in the future.

Then again, as Harper notes, maybe this particular one is not a coincidence.

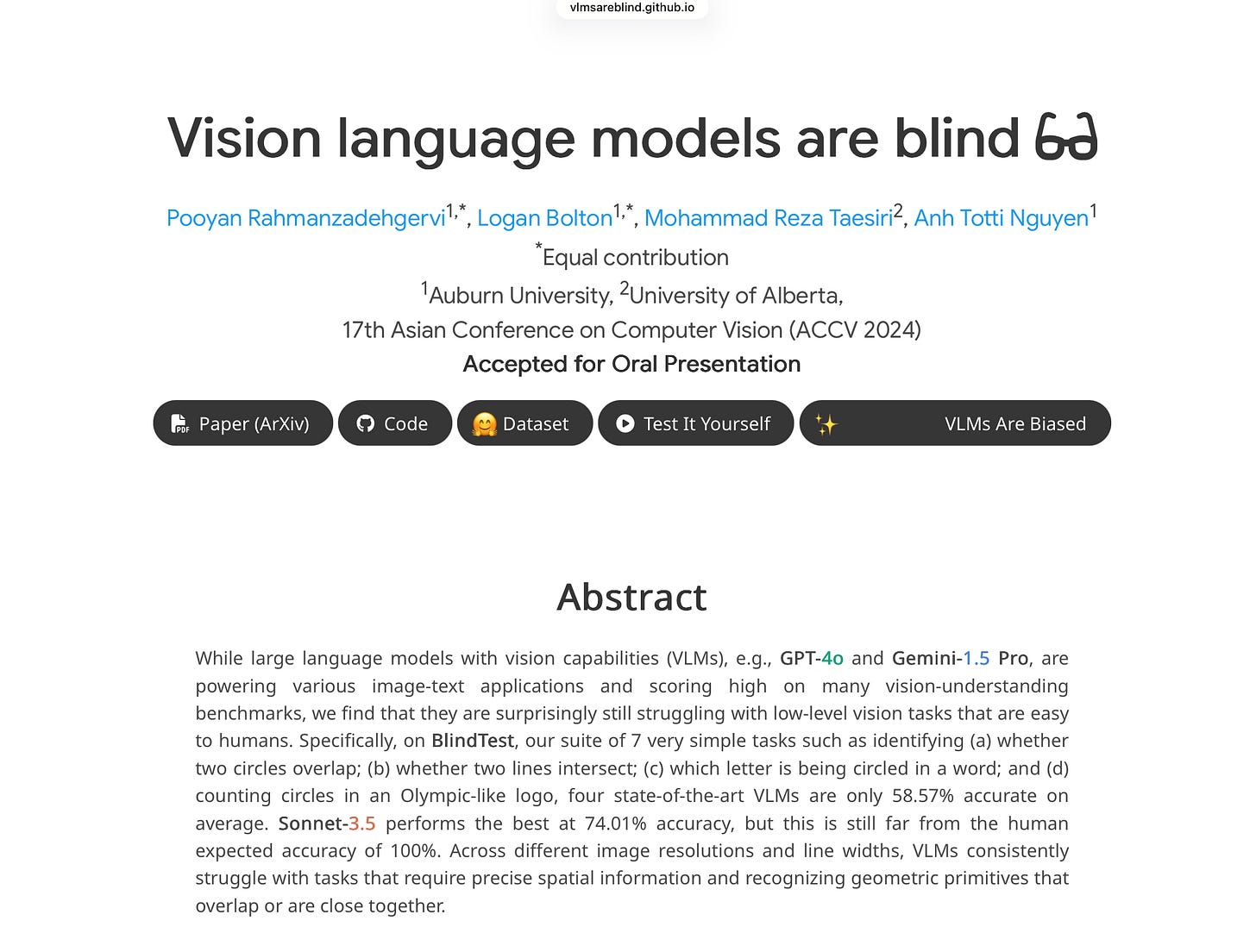

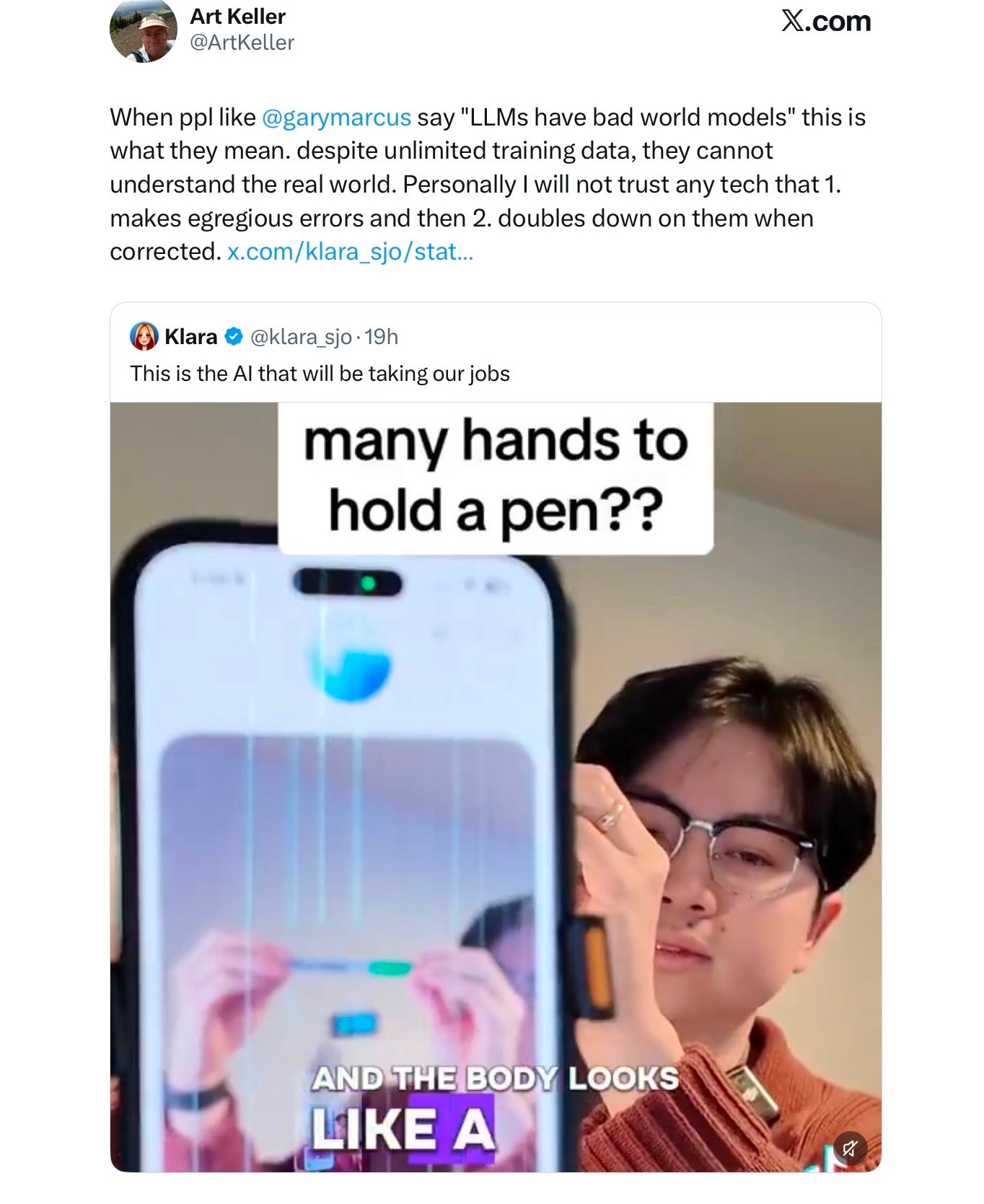

The second is: We can certainly expect incidents of this type, and more of them. Generative AI continues to have serious problems with reasoning and with visual cognition, as, for example, a series of studies by Anh Totti Nguyen has shown, a string of papers like these:

And of course generative AI still has problems with common sense, as an endless of stream of examples have shown, this one involving circulating on X today:

Meanwhile, unless and until the military does actual empirical studies on collateral damage, we won’t really know whether AI is helping or hurting. Mistargeting isn’t new, but using unreliable AI on vibes is fraught with peril.

(More broadly, the military use of AI needs to be a granular question. We might find, for example, that AI helps with logistics and planning but makes more errors in targeting. Mileage may vary according to the task, and may be worse in unfamiliar situations, given the inherent tendencies of generative AI.)

There is a second problem, a moral problem, that goes beyond the technical. The technical problem is that current AI simply isn’t reliable; mistakes will absolutely made. Some will cost lives, some will cost many lives. Some may lead to further escalation (a mass killing of school children could well do that); in the worst case, a series of escalations triggered by AI-triggered mistakes could lead to a nuclear war. Given the current status in the Middle East, this concern is not merely academic.

The moral problem is that militaries may well wish to use AI to cloak moral responsibility. One can, for example, use an AI tool to select targets and blame the AI. It is important to realize that real choices are made at the front end by those who use the AI. How many civilian casualties are acceptable? What error rate is permissible? AI can follow a set of criteria (with more or less precision depending on the quality of the algorithms and data), but humans set those criteria. In my own view, the biggest problem with the algorithms targeting Gaza was not necessarily the algorithms per se (about which not much may be public) but the decision to tolerate a large number of civilian casualties as part of the targeting.

By analogy, if one rolled dice (a physical instantiation of a very simple algorithm) to pick targets, one would not blame the dice for the deaths, but those who chose to leave life or death to chance in the first place.

We should absolutely want any AI that is used for war to be as precise and reliable as possible, minimizing casualties, but we should also never forget that those who use them are responsible for decisions about how many casualties are acceptable. And it should be incumbent on them to understand the limitations and inaccuracies of the algorithms they choose.

Whether current AI algorithms are precise (probably they aren’t), and whether humans are involved in the specific selection of targets, those who use military algorithms bear responsibility for the outcomes they produce.

The race to shove AI into everything is grossly premature, because the tech fundamentally lacks reliability.

Meanwhile, the chance that we will get straight answers is probably close to zero.

Altman, for his part, doesn’t seem to care, having signed a contract entirely full of holes, despite making noises about red lines.

I don’t want to say “this sucks,” but this situation really and truly sucks. Many people, perhaps thousands, maybe more, will die, needlessly.

Gary Marcus (@garymarcus), scientist, best-selling author, and entrepreneur, is deeply concerned about current AI, but really hoping we might do better. He spoke to the U.S. Senate on May 16, 2023 and is the co-author of the award-winning book Rebooting AI, as well as host of the new podcast Humans versus Machines.