Is mathematical beauty real? Or is it just a subjective, human ‘wow’ that is becoming redundant in an AI age?

- by Rita Ahmadi

Is mathematical beauty real? Or is it just a subjective, human ‘wow’ that is becoming redundant in an AI age?

- by Rita Ahmadi

Rahim Nathwani is a technologist based in San Francisco, making businesses better with tech and AI. He believes almost everyone can and should learn more math. His 9-year-old son is on track to complete Algebra 1 before 5th grade.

There is a pattern in American math education reform. An organization claims that a new teaching approach produces dramatic gains. Schools and districts adopt it. Years later, when someone checks the evidence, the gains turn out to be overstated, the methodology turns out to be flawed, and the students who were promised a better education are worse off than before.

The organizations driving these reforms say they want equity. But when their evidence doesn’t hold up, the children who suffer most are the ones these reforms were supposed to help: kids from low-income families, whose parents can’t hire tutors to fill the gaps.

This pattern has played out at least three times with research associated with YouCubed, one of the most influential math education organizations in the country.

YouCubed, a Stanford-based initiative led by Professor Jo Boaler, recently published a PDF claiming dramatic math score improvements in Healdsburg Unified School District in California. The chart showed a compelling story: scores starting very low, climbing steadily, ending impressively high. It’s the kind of result that gets shared in school board meetings and cited in policy decisions.

There was one problem: The numbers don’t match the public record.

California publishes its student test data openly. Anyone can look it up. For the most recent year, YouCubed’s chart and the state data roughly agree: about 75% of 5th graders at Healdsburg meet grade-level standards. But for the baseline year (the “before” picture that makes the improvement look dramatic), YouCubed’s chart shows approximately 24%. The state’s official data for the same district, year, and grade band shows approximately 44%.

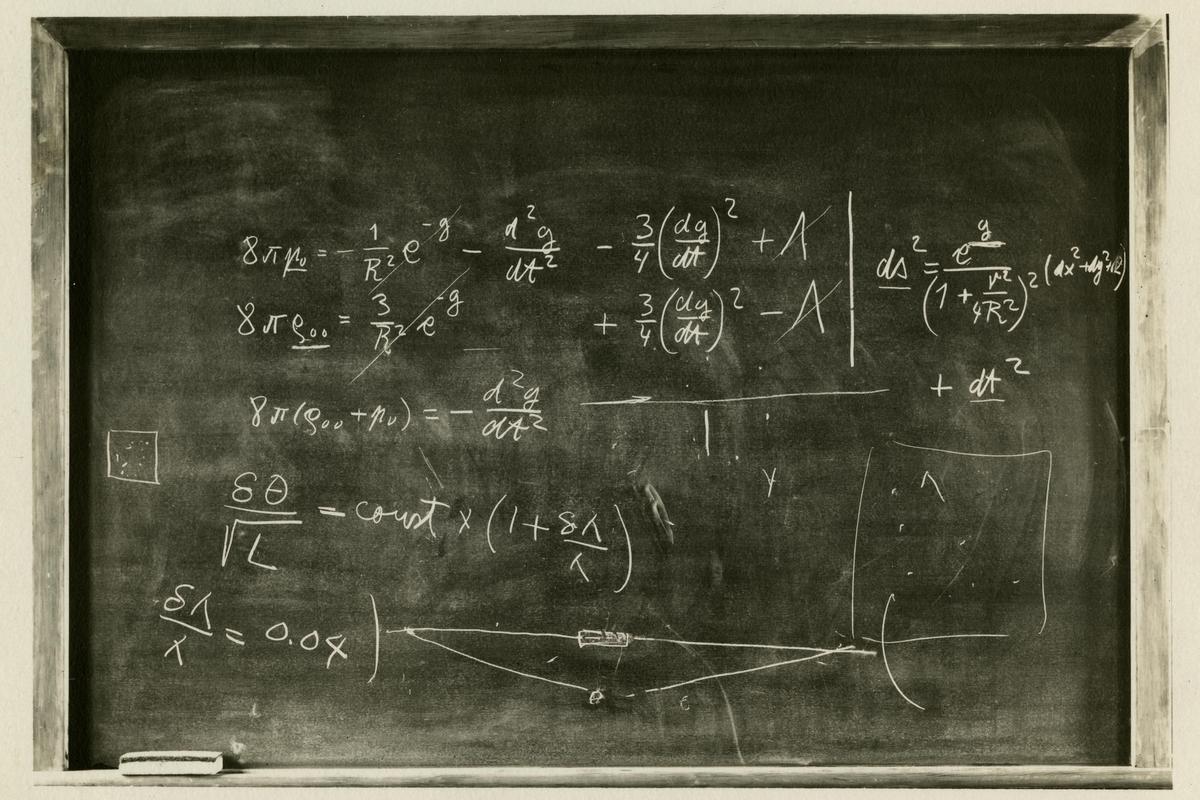

Here’s the chart from the YouCubed PDF:

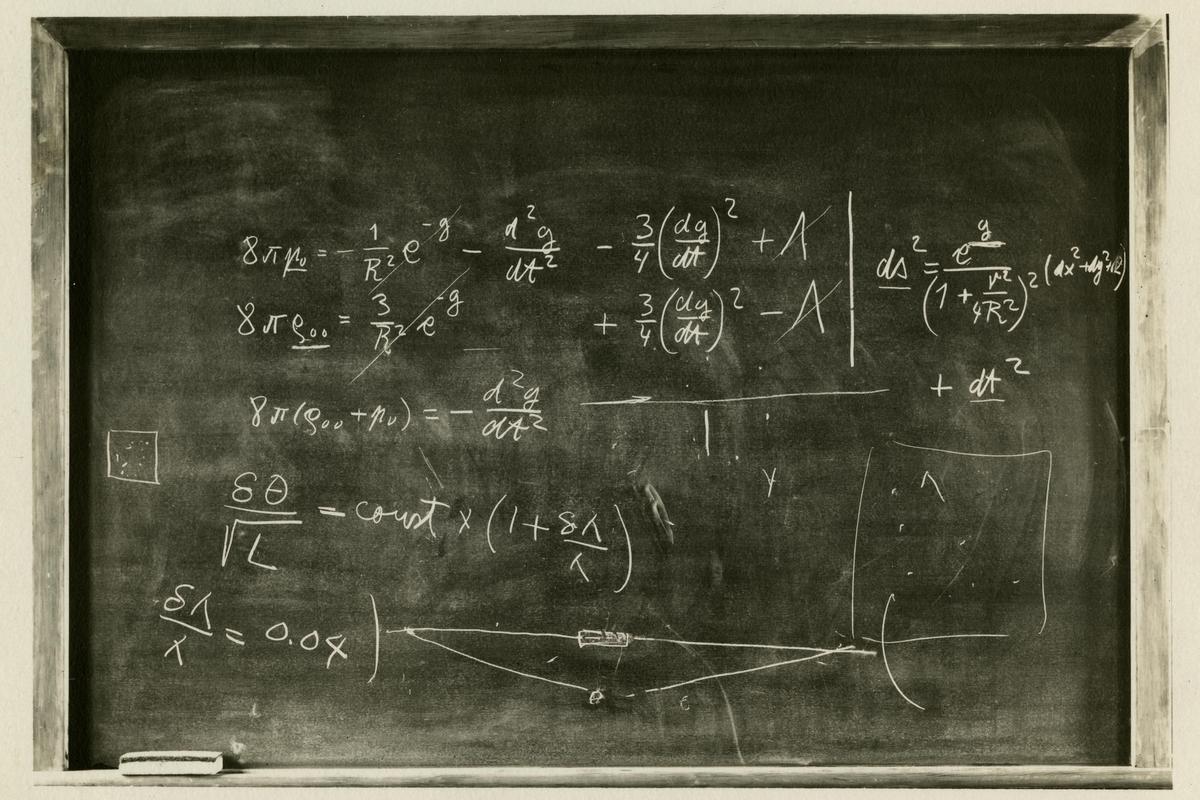

And here’s a recreation of the chart based on official government numbers:

That’s not a rounding difference. That’s a gap of 20 percentage points, and it runs in exactly the direction that makes the improvement story look better.

When you replace YouCubed’s baseline with the actual public data, the narrative changes completely. Scores were roughly flat for several years, then showed a recent uptick. That might be a legitimate result. But it is not the dramatic turnaround that YouCubed presented to educators and policymakers, and which Jo Boaler shared on X.

In education research circles, it’s common to see researchers exclude certain subgroups from their data. The most frequent justification is something like: “We excluded chronically absent students because they didn’t receive the full intervention.”

That’s a methodologically reasonable thing to do, as long as you say you’re doing it and explain why.

The YouCubed document makes no mention of any data exclusion. But let’s ask: could data exclusion explain the discrepancy?

Here’s the problem. If you exclude chronically absent students from a proficiency calculation, you would generally expect the remaining percentage to go up, not down. Students who miss a lot of school typically perform worse on tests. Take them out of the calculation, and the percentage of students who meet standards would likely increase, not decrease.

But YouCubed’s 2016–2017 figure (24%) is far below the state’s figure (44%). That means their exclusion would have had to somehow remove the higher-performing students from the calculation. That is the opposite of what “excluding chronically absent students” would do.

We cannot think of a legitimate methodological reason why a district’s proficiency rate would be nearly cut in half by a data exclusion. If there is one, Youcubed’s report should explain it. It doesn’t.

Even setting aside the data discrepancy, there is a deeper methodological problem with the chart — one that matters even if every number in it were correct.

The chart compares “5th graders in 2017” to “5th graders in 2023.” These are entirely different groups of children. The kids who were in 5th grade in 2017 are in their early 20s now. They are not the same kids who were tested in 2023.

Imagine you run a tutoring program. In Year 1, you tutor a class of students who happen to come from lower-income families and score an average of 60 on a test. In Year 5, a different group of students — from more affluent families, in a district that has added new staff — scores an average of 80. Can you claim your tutoring program caused the improvement? Of course not.

The right way to evaluate whether an educational intervention works is to track the same group of students over time and see how they progress. This is called a “cohort study.” It’s standard in medical research (think clinical trials), and it’s the gold standard in education research too.

We went ahead and pulled the cohort data from California’s public records. We tracked each group of students as they moved through the grades. What did that analysis show? Here it is:

It did not show consistent improvement across cohorts. The picture was much more mixed than the YouCubed chart suggests.

In fact, if we look at the most recent cohorts (the kids who entered 3rd grade in 2018 or later), we see that almost all cohorts (grades) have a downward trend: the chance that any given kid meets state standards in math goes down as they spend more years at Healdsburg school district.

This matters because the entire point of the YouCubed document is presumably to persuade: to show that the YouCubed approach works, and that other districts should adopt it. If the underlying analysis is methodologically flawed (and if the baseline data appears to be inaccurate) then that persuasion is built on sand.

This would be easier to set aside if it were an isolated mistake. It is not.

YouCubed’s influence traces back to Professor Boaler’s most celebrated research: the “Railside” study, published in 2008, which claimed that a reform-math approach at a California high school produced dramatic gains, especially for minority students. That study became enormously influential. It shaped curricula, frameworks, and professional development programs across the country.

In 2012, two Stanford mathematics professors and several colleagues published an extended critique. They raised serious concerns: the school had been misrepresented, the data couldn’t be independently verified, and the conclusions overstated what the evidence showed. Rather than release the underlying data for independent review, Professor Boaler characterized the critique as harassment.

The data was never made fully available. The study remains widely cited.

In 2023, California adopted a new Mathematics Framework that drew heavily on Boaler’s ideas and YouCubed’s recommendations. The framework discouraged ability grouping, de-emphasized procedural fluency, and delayed access to advanced math courses — all in the name of equity.

More than 1,000 scientists and mathematicians signed an open letter objecting. Their concerns: the framework cited research selectively, dismissed evidence from high-performing countries, and would likely harm the students it claimed to help — particularly those aiming for STEM careers.

A Stanford mathematician who reviewed the framework’s citations in detail documented numerous cases where cited studies either didn’t support the claims being made or actively contradicted them. Misrepresented citations, like misrepresented data, are hard to attribute to innocent error when they consistently run in the same direction.

Three cases. In each one, research associated with the same organization claimed dramatic results. In each one, outside review found serious problems with the evidence. And in each one, the discrepancies ran in the same direction: making the reform approach look more effective than the data actually showed.

A single error is understandable. Research is hard, and mistakes happen. But when the mistakes consistently flatter the same conclusion, the most straightforward explanation is not bad luck.

This matters because education policy is downstream of evidence. When a district eliminates ability grouping, it cites research. When a state delays algebra, it cites research. When a school board adopts a new curriculum, it cites research. If that research is unreliable, every decision built on it is compromised.

When a math reform fails, the cost is not distributed equally.

Families with resources respond to a weak math program the same way they respond to every institutional failure: they route around it. They hire a tutor. They enroll in a supplemental program. They move to a different district. And this last dynamic is perhaps the most destructive: declining public school enrollment means system-wide strain, fewer resources for schools and teachers, and eventual school closures. This phenomenon is showing up across the country, and it seems to be driven by wealthier, white, and asian families, especially those in deep-blue districts experiencing acute education dysfunction. Seattle has seen thousands of families leave public schools, and private schools in San Francisco are brimming with new applicants.

Families earning $200,000 a year have options and are evidently ready and willing to use them.

A family earning $40,000 does not. When school math instruction is the only math instruction a child receives, the quality of that instruction is the ceiling on that child’s opportunity. A low-income child whose school adopted a curriculum based on overstated evidence doesn’t get a do-over.

The cruelest irony is that these reforms are justified in the language of equity. The children they claim to champion are the ones with the fewest alternatives when the reforms don’t work.

None of this means that math education shouldn’t evolve, or that traditional approaches are beyond criticism. But it does mean that the organizations driving reform need to meet a basic evidentiary standard: the same standard we’d expect of a pharmaceutical company claiming its drug works.

That standard is straightforward. When you publish results, the underlying data should be available for independent review. When your chart shows a number, it should match the public record. When you cite a study, the study should actually support the claim you’re making. And when someone finds an error, the response should be a correction, not an accusation.

These are not hostile demands. They are the minimum that parents, teachers, and policymakers deserve before reshaping how children learn mathematics.

One bad chart would be forgivable. But what we’ve described here is a pattern: influential organizations are shaping how millions of children learn math based on research that hasn’t survived basic scrutiny, and the kids who pay the price are the same ones the reforms were supposed to help.

Your child’s math education deserves evidence that holds up when someone checks.

The post The Evolving Foundations of Math first appeared on Quanta Magazine

What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.

— Joseph Weizenbaum, creator of ELIZA, in 1976 (via)

Tags: ai-ethics, ai, computer-history, internet-archive

Never let them tell you that enshittification was a mystery. Enshittification isn't downstream of the "iron laws of economics" or an unrealistic demand by "consumers" to get stuff for free.

Enshittification comes from specific policy choices, made by named individuals, that had the foreseeable and foreseen result of making the web worse:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/10/07/take-it-easy/#but-take-it

Like, there was once a time when an ever-increasing proportion of web users kept tabs on what was going on with RSS. RSS is a simple, powerful way for websites to publish "feeds" of their articles, and for readers to subscribe to those feeds and get notified when something new was posted, and even read that new material right there in your RSS reader tab or app.

RSS is simple and versatile. It's the backbone of podcasts (though Apple and Spotify have done their best to kill it, along with public broadcasters like the BBC, all of whom want you to switch to proprietary apps that spy on you and control you). It's how many automated processes communicate with one another, untouched by human hands. But above all, it's a way to find out when something new has been published on the web.

RSS's liftoff was driven by Google, who released a great RSS reader called "Google Reader" in 2007. Reader was free and reliable, and other RSS readers struggled to compete with it, with the effect that most of us just ended up using Google's product, which made it even harder to launch a competitor.

But in 2013, Google quietly knifed Reader. I've always found the timing suspicious: it came right in the middle of Google's desperate scramble to become Facebook, by means of a product called Google Plus (G+). Famously, Google product managers' bonuses depended on how much G+ engagement they drove, with the effect that every Google product suddenly sprouted G+ buttons that either did something stupid, or something that confusingly duplicated existing functionality (like commenting on Youtube videos).

Google treated G+ as an existential priority, and for good reason. Google was running out of growth potential, having comprehensively conquered Search, and having repeatedly demonstrated that Search was a one-off success, with nearly every other made-in-Google product dying off. What successes Google could claim were far more modest, like Gmail, Google's Hotmail clone. Google augmented its growth by buying other peoples' companies (Blogger, YouTube, Maps, ad-tech, Docs, Android, etc), but its internal initiatives were turkeys.

Eventually, Wall Street was going to conclude that Google had reached the end of its growth period, and Google's shares would fall to a fraction of their value, with a price-to-earnings ratio commensurate with a "mature" company.

Google needed a new growth story, and "Google will conquer Facebook's market" was a pretty good one. After all, investors didn't have to speculate about whether Facebook was profitable, they could just look at Facebook's income statements, which Google proposed to transfer to its own balance sheet. The G+ full-court press was as much a narrative strategy as a business strategy: by tying product managers' bonuses to a metric that demonstrated G+'s rise, Google could convince Wall Street that they had a lot of growth on their horizon.

Of course, tying individual executives' bonuses to making a number go up has a predictably perverse outcome. As Goodhart's law has it, "Any metric becomes a target, and then ceases to be a useful metric." As soon as key decision-makers' personal net worth depending on making the G+ number go up, they crammed G+ everywhere and started to sneak in ways to trigger unintentional G+ sessions. This still happens today – think of how often you accidentally invoke an unbanishable AI feature while using Google's products (and products from rival giant, moribund companies relying on an AI narrative to convince investors that they will continue to grow):

https://pluralistic.net/2025/05/02/kpis-off/#principal-agentic-ai-problem

Like I said, Google Reader died at the peak of Google's scramble to make the G+ number go up. I have a sneaking suspicion that someone at Google realized that Reader's core functionality (helping users discover, share and discuss interesting new web pages) was exactly the kind of thing Google wanted us to use G+ for, and so they killed Reader in a bid to drive us to the stalled-out service they'd bet the company on.

If Google killed Reader in a bid to push users to discover and consume web pages using a proprietary social media service, they succeeded. Unfortunately, the social media service they pushed users into was Facebook – and G+ died shortly thereafter.

For more than a decade, RSS has lain dormant. Many, many websites still emit RSS feeds. It's a default behavior for WordPress sites, for Ghost and Substack sites, for Tumblr and Medium, for Bluesky and Mastodon. You can follow edits to Wikipedia pages by RSS, and also updates to parcels that have been shipped to you through major couriers. Web builders like Jason Kottke continue to surface RSS feeds for elaborate, delightful blogrolls:

There are many good RSS readers. I've been paying for Newsblur since 2011, and consider the $36 I send them every year to be a very good investment:

But RSS continues to be a power user-coded niche, despite the fact that RSS readers are really easy to set up and – crucially – make using the web much easier. Last week, Caroline Crampton (co-editor of The Browser) wrote about her experiences using RSS:

https://www.carolinecrampton.com/the-view-from-rss/

As Crampton points out, much of the web (including some of the cruftiest, most enshittified websites) publish full-text RSS feeds, meaning that you can read their articles right there in your RSS reader, with no ads, no popups, no nag-screens asking you to sign up for a newsletter, verify your age, or submit to their terms of service.

It's almost impossible to overstate how superior RSS is to the median web page. Imagine if the newsletters you followed were rendered with black, clear type on a plain white background (rather than the sadistically infinitesimal, greyed-out type that designers favor thanks to the unkillable urban legend that black type on a white screen causes eye-strain). Imagine reading the web without popups, without ads, without nag screens. Imagine reading the web without interruptors or "keep reading" links.

Now, not every website publishes a fulltext feed. Often, you will just get a teaser, and if you want to read the whole article, you have to click through. I have a few tips for making other websites – even ones like Wired and The Intercept – as easy to read as an RSS reader, at least for Firefox users.

Firefox has a built-in "Reader View" that re-renders the contents of a web-page as black type on a white background. Firefox does some kind of mysterious calculation to determine whether a page can be displayed in Reader View, but you can override this with the Activate Reader View, which adds a Reader View toggle for every page:

https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/activate-reader-view/

Lots of websites (like The Guardian) want you to login before you can read them, and even if you pay to subscribe to them, these sites often want you to re-login every time you visit them (especially if you're running a full suite of privacy blockers). You can skip this whole process by simply toggling Reader View as soon as you get the login pop up. On some websites (like The Verge and Wired), you'll only see the first couple paragraphs of the article in Reader View. But if you then hit reload, the whole article loads.

Activate Reader View puts a Reader View toggle on every page, but clicking that toggle sometimes throws up an error message, when the page is so cursed that Firefox can't figure out what part of it is the article. When this happens, you're stuck reading the page in the site's own default (and usually terrible) view. As you scroll down the page, you will often hit pop-ups that try to get you to sign up for a mailing list, agree to terms of service, or do something else you don't want to do. Rather than hunting for the button to close these pop-ups (or agree to objectionable terms of service), you can install "Kill Sticky," a bookmarklet that reaches into the page's layout files and deletes any element that isn't designed to scroll with the rest of the text:

https://github.com/t-mart/kill-sticky

Other websites (like Slashdot and Core77) load computer-destroying Javascript (often as part of an anti-adblock strategy). For these, I use the "Javascript Toggle On and Off" plugin, which lets you create a blacklist of websites that aren't allowed to run any scripts:

https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/javascript-toggler/

Some websites (like Yahoo) load so much crap that they defeat all of these countermeasures. For these websites, I use the "Element Blocker" plug-in, which lets you delete parts of the web-page, either for a single session, or permanently:

https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/element-blocker/

It's ridiculous that websites put so many barriers up to a pleasant reading experience. A slow-moving avalanche of enshittogenic phenomena got us here. There's corporate enshittification, like Google/Meta's monopolization of ads and Meta/Twitter's crushing of the open web. There's regulatory enshittification, like the EU's failure crack down on companies the pretend that forcing you to click an endless stream of "cookie consent" popups is the same as complying with the GDPR.

Those are real problems, but they don't have to be your problem, at least when you want to read the web. A couple years ago, I wrote a guide to using RSS to improve your web experience, evade lock-in and duck algorithmic recommendation systems:

Customizing your browser takes this to the next level, disenshittifying many websites – even if they block or restrict RSS. Most of this stuff only applies to desktop browsers, though. Mobile browsers are far more locked down (even mobile Firefox – remember, every iOS browser, including Firefox, is just a re-skinned version of Safari, thanks to Apple's ban rival browser engines). And of course, apps are the worst. An app is just a website skinned in the right kind of IP to make it a crime to improve it in any way:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/07/treacherous-computing/#rewilding-the-internet

And even if you do customize your mobile browser (Android Firefox lets you do some of this stuff), many apps (Twitter, Tumblr) open external links in their own browser (usually an in-app Chrome instance) with all the bullshit that entails.

The promise of locked-down mobile platforms was that they were going to "just work," without any of the confusing customization options of desktop OSes. It turns out that taking away those confusing customization options was an invitation to every enshittifier to turn the web into an unreadable, extractive, nagging mess. This was the foreseeable – and foreseen – consequence of a new kind of technology where everything that isn't mandatory is prohibited:

https://memex.craphound.com/2010/04/01/why-i-wont-buy-an-ipad-and-think-you-shouldnt-either/

Users fume over Outlook.com email 'carnage' https://www.theregister.com/2026/03/04/users_fume_at_outlookcom_email/

You Bought Zuck’s Ray-Bans. Now Someone in Nairobi Is Watching You Poop. https://blog.adafruit.com/2026/03/04/you-bought-zucks-ray-bans-now-someone-in-nairobi-is-watching-you-poop/

Indefinite Book Club Hiatus https://whatever.scalzi.com/2026/03/03/indefinite-book-club-hiatus/

Art Bits from HyperCard https://archives.somnolescent.net/web/mari_v2/junk/hypercard/

#25yrsago 200 Eyemodule photos from Disneyland https://craphound.com/030401/

#20yrsago Fourth Amendment luggage tape https://ideas.4brad.com/node/367

#15yrsago Glenn Beck’s syndicator runs a astroturf-on-demand call-in service for radio programs https://web.archive.org/web/20110216081007/http://www.tabletmag.com/life-and-religion/58759/radio-daze/

#15yrsago 20 lies from Scott Walker https://web.archive.org/web/20110308062319/https://filterednews.wordpress.com/2011/03/05/20-lies-and-counting-told-by-gov-walker/

#10yrsago The correlates of Trumpism: early mortality, lack of education, unemployment, offshored jobs https://web.archive.org/web/20160415000000*/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/03/04/death-predicts-whether-people-vote-for-donald-trump/

#10yrsago Hacking a phone’s fingerprint sensor in 15 mins with $500 worth of inkjet printer and conductive ink https://web.archive.org/web/20160306194138/http://www.cse.msu.edu/rgroups/biometrics/Publications/Fingerprint/CaoJain_HackingMobilePhonesUsing2DPrintedFingerprint_MSU-CSE-16-2.pdf

#10yrsago Despite media consensus, Bernie Sanders is raising more money, from more people, than any candidate, ever https://web.archive.org/web/20160306110848/https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/sanders-keeps-raising-money–and-spending-it-a-potential-problem-for-clinton/2016/03/05/a8d6d43c-e2eb-11e5-8d98-4b3d9215ade1_story.html

#10yrsago Calculating US police killings using methodologies from war-crimes trials https://granta.com/violence-in-blue/

#1yrago Brother makes a demon-haunted printer https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/05/printers-devil/#show-me-the-incentives-i-will-show-you-the-outcome

#1yrago Two weak spots in Big Tech economics https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/06/privacy-last/#exceptionally-american

Barcelona: Enshittification with Simona Levi/Xnet (Llibreria Finestres), Mar 20

https://www.llibreriafinestres.com/evento/cory-doctorow/

Berkeley: Bioneers keynote, Mar 27

https://conference.bioneers.org/

Montreal: Bronfman Lecture (McGill) Apr 10

https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/artificial-intelligence-the-ultimate-disrupter-tickets-1982706623885

London: Resisting Big Tech Empires (LSBU)

https://www.tickettailor.com/events/globaljusticenow/2042691

Berlin: Re:publica, May 18-20

https://re-publica.com/de/news/rp26-sprecher-cory-doctorow

Berlin: Enshittification at Otherland Books, May 19

https://www.otherland-berlin.de/de/event-details/cory-doctorow.html

Hay-on-Wye: HowTheLightGetsIn, May 22-25

https://howthelightgetsin.org/festivals/hay/big-ideas-2

Tanner Humanities Lecture (U Utah)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6Yf1nSyekI

The Lost Cause

https://streets.mn/2026/03/02/book-club-the-lost-cause/

Should Democrats Make A Nuremberg Caucus? (Make It Make Sense)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MWxKrnNfrlo

Making The Internet Suck Less (Thinking With Mitch Joel)

https://www.sixpixels.com/podcast/archives/making-the-internet-suck-less-with-cory-doctorow-twmj-1024/

"Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, October 7 2025

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374619329/enshittification/

"Picks and Shovels": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about the heroic era of the PC, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2025 (https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865908/picksandshovels).

"The Bezzle": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about prison-tech and other grifts, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2024 (thebezzle.org).

"The Lost Cause:" a solarpunk novel of hope in the climate emergency, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), November 2023 (http://lost-cause.org).

"The Internet Con": A nonfiction book about interoperability and Big Tech (Verso) September 2023 (http://seizethemeansofcomputation.org). Signed copies at Book Soup (https://www.booksoup.com/book/9781804291245).

"Red Team Blues": "A grabby, compulsive thriller that will leave you knowing more about how the world works than you did before." Tor Books http://redteamblues.com.

"Chokepoint Capitalism: How to Beat Big Tech, Tame Big Content, and Get Artists Paid, with Rebecca Giblin", on how to unrig the markets for creative labor, Beacon Press/Scribe 2022 https://chokepointcapitalism.com

"Enshittification, Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It" (the graphic novel), Firstsecond, 2026

"The Post-American Internet," a geopolitical sequel of sorts to Enshittification, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2027

"Unauthorized Bread": a middle-grades graphic novel adapted from my novella about refugees, toasters and DRM, FirstSecond, 2027

"The Memex Method," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2027

Today's top sources:

Currently writing: "The Post-American Internet," a sequel to "Enshittification," about the better world the rest of us get to have now that Trump has torched America (1012 words today, 45361 total)

"The Post-American Internet," a short book about internet policy in the age of Trumpism. PLANNING.

A Little Brother short story about DIY insulin PLANNING

This work – excluding any serialized fiction – is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. That means you can use it any way you like, including commercially, provided that you attribute it to me, Cory Doctorow, and include a link to pluralistic.net.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Quotations and images are not included in this license; they are included either under a limitation or exception to copyright, or on the basis of a separate license. Please exercise caution.

Blog (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

Newsletter (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

https://pluralistic.net/plura-list

Mastodon (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

Bluesky (no ads, possible tracking and data-collection):

https://bsky.app/profile/doctorow.pluralistic.net

Medium (no ads, paywalled):

https://doctorow.medium.com/

https://twitter.com/doctorow

Tumblr (mass-scale, unrestricted, third-party surveillance and advertising):

https://mostlysignssomeportents.tumblr.com/tagged/pluralistic

"When life gives you SARS, you make sarsaparilla" -Joey "Accordion Guy" DeVilla

READ CAREFULLY: By reading this, you agree, on behalf of your employer, to release me from all obligations and waivers arising from any and all NON-NEGOTIATED agreements, licenses, terms-of-service, shrinkwrap, clickwrap, browsewrap, confidentiality, non-disclosure, non-compete and acceptable use policies ("BOGUS AGREEMENTS") that I have entered into with your employer, its partners, licensors, agents and assigns, in perpetuity, without prejudice to my ongoing rights and privileges. You further represent that you have the authority to release me from any BOGUS AGREEMENTS on behalf of your employer.

ISSN: 3066-764X