Let the record state that I love Scott Alexander. I’ve been a reader for over a decade and count him among the sharpest and most important public intellectuals working today. I credit essays like I Can Tolerate Anything Except the Outgroup with articulating feelings I had been having for years but didn’t yet have the words to express, thereby giving me new insights and the vocabulary to discuss them. I don’t read everything he writes anymore (who has the time?), but I remain a loyal subscriber and to this day find much of value in his prolific output.

But. (With an introduction like that, you know there must be a “but” coming). I increasingly find myself in disagreement with Scott’s essays on social issues and public policy, despite broadly sharing his small-L liberal outlook. I often see him deploy arguments I consider specious in a manner I find off-putting. And I blame his devotion to The Church of Graphs.

The Church of Graphs is dedicated to the meta-belief that knowledge must be formalized and quantifiable to be worthy of consideration. It demands that its adherents reject the evidence of their own eyes in favor of official facts and figures stamped with the imprimatur of a priestly expert class. Church members typically have curious blind spots in their understanding of the world that strike non-believers as ridiculous, but many very intelligent people are believers. Scott is a Bishop.

There’s no better example of what I mean than two of his recent posts, about crime and disorder.

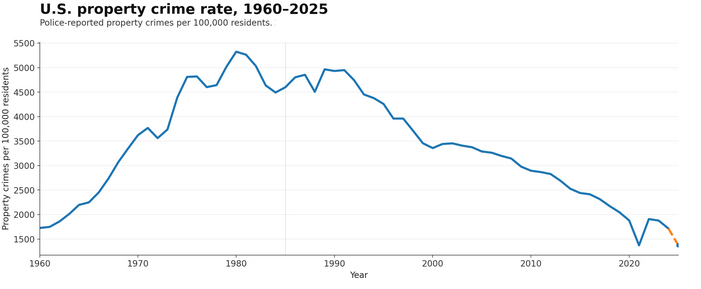

First we have Record Low Crime Rates Are Real, Not Just Reporting Bias Or Improved Medical Care. The title says most of what you need to know, and the article argues that falling reported crime rates are real, not a result of people being so jaded about crime and the justice system that they don’t bother reporting it anymore. The reference to medical care is addressing a popular argument that record-low homicide rates would be much higher in the absence of advances in emergency room care that turn murders into mere assaults, and Scott argues convincingly that this isn’t true. But while homicide is the single most reliably recorded crime due to the presence of a body, reported crime is down across the board. Here’s the rate of property crime, for example.

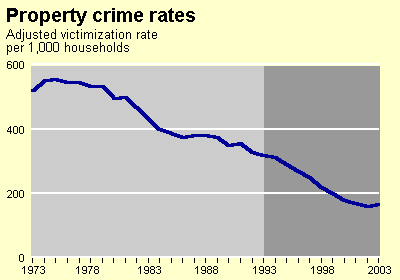

We have reason to believe that this decline isn’t solely due to reporting bias because the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), which polls randomly selected residents to ask if they have been victims of a crime, also reports a large decline. These rates are per household rather than per individual, and do not include crimes committed against businesses. But this second, independent data source corroborates the narrative of falling crime rates.

Next we have Crime As Proxy For Disorder, in which Scott starts off unusually back-footed due to the amount of pushback he received on the first post. Scott’s discussion threads are quite lively and his audience enormous, so the usual concept of a “ratio” doesn’t apply to him as it would to you or I. But still: the original article attracted over 700 comments on just 360 likes at the time of this writing. Scott’s audience was not buying what he was selling. In Scott’s words:

The problem: people hate crime and think it’s going up. But actually, crime barely affects most people and is historically low. So what’s going on?

In our discussion yesterday, many commenters proposed that the discussion about “crime” was really about disorder.

All the graphs say that crime is declining, but people believe it’s getting worse. This includes many members of Scott’s way-above-average-intelligence readership. Why is that? Scott proposes that maybe people’s perceptions on this topic are based on disorder, and proposes several indicators for disorder: litter, graffiti, shoplifting, tent cities. He then spends the rest of the post demonstrating with impeccably sourced and credentialed figures why none of these disorder indicators are actually getting worse, either. They’re all getting better, or there isn’t enough data to say.

Littering seems to be down

Graffiti is unclear, probably varies by city.

Shoplifting seems to be up 20% from generational lows, but still lower than 1990s.

Homelessness seems to be up 25% from generational lows, and equal to the 1990s.

Tent encampments are hard to measure nationally; in SF, they are below pre-pandemic levels.

I’m not here to argue with Scott’s statistics. I think they’re about as accurate as we could hope to make them. I’m here to argue that you don’t require them to make sense of the world, and to give you permission to trust your own eyes on matters that affect your life.

Ways of knowing what’s true, and why to believe things

There’s a pretty old blog post circulating among rationalist types about three different ways of knowing things and why each is important. They have abstruse Greek names: doxa, episteme, and gnosis. These terms allow people using them to feel like they possess powerful esoteric knowledge about the world, but the concepts themselves are simple and useful

Doxa is what we know because someone told us. If you read a book and learn a fact from it, or it changes your opinion on something, what you’ve learned is doxa.

Episteme is what we know because we have used logic and reasoning to reach a conclusion from first principles or observation. If you read a policy statement and convince yourself it can’t work by thinking through obvious second-order effects it would create, your opinion is episteme.

Gnosis is what we know because we’ve seen or experienced it firsthand. When you generalize about “how people are likely to treat a stranger in need” or “how should one live to be happy” based on examples from your own life, you’re applying gnosis.

When I talk about The Church of Graphs, I am talking about people who privilege doxa over gnosis and episteme. Members of The Church of Graphs live by one primary commandment: thou shalt not believe your lying eyes.

When a Church member encounters evidence from gnosis that would seem to contradict the sacred doxa, they will tie themselves in knots to defend the doxa as still correct, or at least more correct than whatever is being offered in contradiction. Say for instance that a Church member sees some guys emptying the shelves of a drug store into garbage bags, and there are other guys selling suspiciously similar merchandise from blankets on the sidewalk around the corner. They notice this happening multiple times over months, and they can’t remember ever seeing the same problem a few years ago; but the Graphs say shoplifting is down overall. The Graphs have supremacy over mere direct experience. And the Church has taught its members how to respond to heretics who claim otherwise.

They’ll begin by reminding you that your own observations are subject to a number of cognitive and other biases, among them Recency Bias and the powerful Availability Bias. Just because things appear to be getting worse to you doesn’t make it so. Your own experiences can’t be said to be representative, after all. Have you collected enough data to be sure? Perhaps they’ll concede that the official figures for crime are necessarily a lower bound, yes, but they’ve always been underreported, and there’s no reason to believe they are more underreported now than in times past. They may even quote part of their creed: “there is no evidence” that underreporting is a bigger problem than it used to be.

Of course, by “evidence” they are referring to doxa and only a particular kind of doxa. Your own experiences, those of people you know, conversations you’ve had with employees at crime-besieged stores, statements from business owners and corporations as they shutter locations due to safety and theft concerns — these are all hearsay, inadmissible forms of knowledge. To the devout, knowledge must be carefully collected, quantified, and vetted through proper channels. The highest blessing such knowledge can receive is when a set of facts and figures passes through a holy sacrament known as peer review, where high priests of the Church risk excommunication by vouching for its veracity.

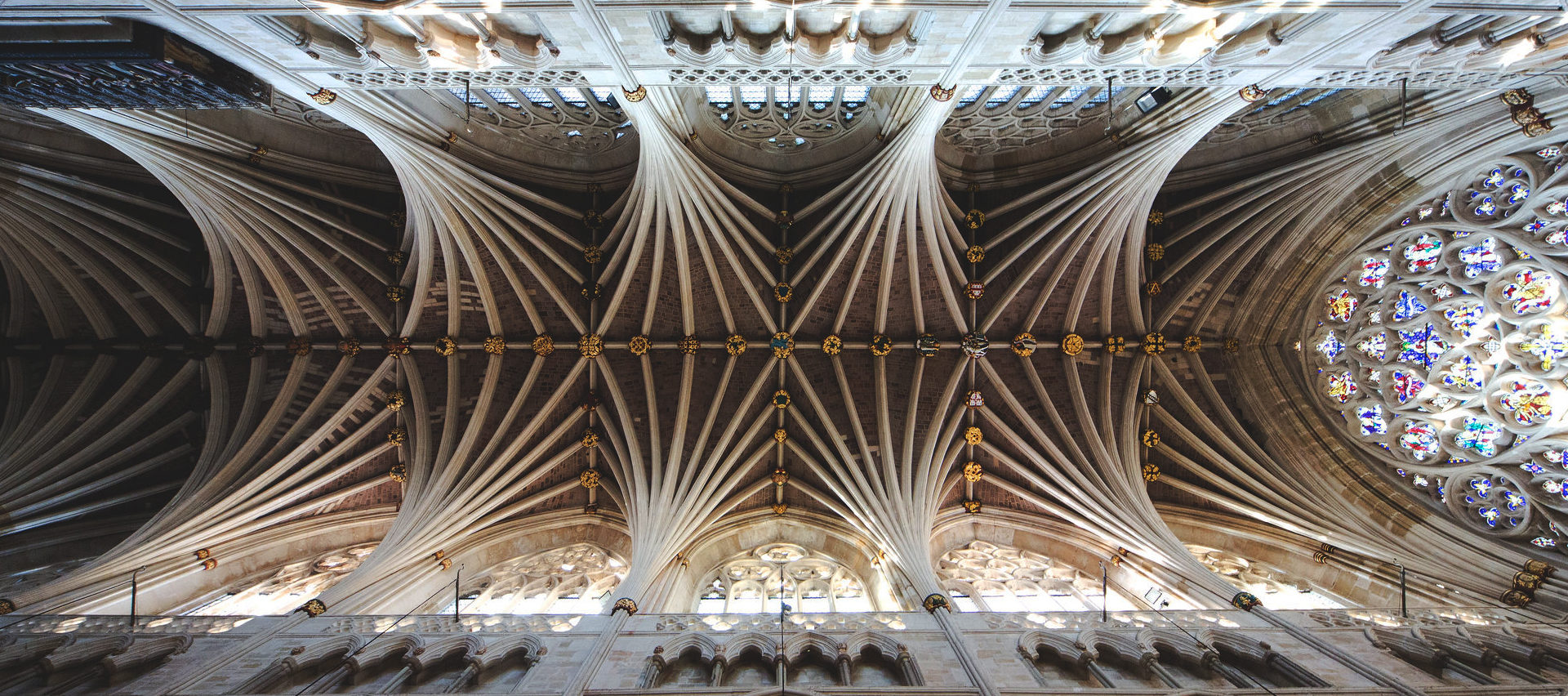

Church members have a second all-important commandment as well: thou shalt not think too hard about the Graphs. Thinking too hard, that is to say, producing episteme by applying reason to the Graphs in a manner that might undermine their conclusions, is strictly forbidden by Church teachings. Let us refer to one of these sacred documents, below.

It is inappropriate for the laity to attempt to practice discernment about these figures, to ask if it is remotely plausible that a city of 600,000 people experienced a scant 200 incidents of a crime as common as shoplifting during any month this century or the last. Worse still would be to allow such questions to cause a crisis of faith, to make one look upon such a Graph and others like it with suspicion, rather than reverence. Certainly the priests have license to ask such questions, and will communicate appropriate explanations and interpretations through one of the proper channels. But for a mere parishioner to attempt the same, without the proper training, and furthermore without the necessary reverence and openness to the Spirit, would be to place oneself in spiritual danger. This could cause one to come to the wrong conclusion, or worse — lose standing among the other deacons of the Church.

But I’m not a Church member, so I have no standing to lose. In fact, I’m something much worse than even a simple heretic: I’m an apostate. I was one of the Church’s most faithful defenders and evangelists, spreading the gospel and commandments far and wide. I only left the Church after it failed me one too many times, after the gap between the Graphs and my personal experiences, and my own faculties of reason, became too wide to ignore. The Church led me to confidently believe too many things that simply weren’t so, too many times.

Let the record state that I’m not graphophobic (the deadliest sin recognized by the Church) — I frequently refer to charts of figures in my own intellectual work and in casual conversation, and hold them to be vital tools to understand the world. But I have been blessed to live long enough to discover the essential frailty of the Graphs, to find shocking cracks in their professional, impassive facades. And, more to the point, I have come to understand that an over-reliance on the Graphs leads to an impoverished and ultimately less accurate, less useful worldview.

The epistemic chain of custody and the mismeasure of misery

Consider the steps that must happen for the knowledge of a crime to reach you, when you rely on official compiled statistics as reflected in the Graphs. First, a crime is committed. And then:

The crime is either noticed by someone, or not. A bicycle stolen from a yard becomes, with enough time and uncertainty between the offense and its noting, merely “lost property”.

Assuming it was noticed, the crime is either reported, or not. Whether the victim considers it worth his time and effort to report depends on a variety of factors: how serious he considers the offense; whether he thinks anything will come of a report; whether it’s required for an insurance settlement; his sense of duty to the social compact in reporting crime; how much time and energy he has to spare; whether he even knows how to report a non-emergency crime, shares a language with the authorities, etc.

Assuming it was reported, the crime is either recorded, or not. Clerical errors of course happen. Paperwork gets lost or misfiled, software bugs prevent forms from being persisted correctly, or lead to their loss after the fact. A whole host of social and political pressures often apply at this step as well. Political officers high in the chain of command are held accountable for the number of reports, how the numbers compare to previous years, their clearance rates, etc. There are a hundred ways up to and including outright fraud to prevent an inconvenient report from being durably recorded and therefore becoming legible.

Assuming it was recorded, the crime is either classified correctly, or not. Think of a time you had an interaction with a police officer, perhaps in the aftermath of an auto collision, and had a chance to review what he wrote about the incident. Was his summary accurate? Or did he get important details wrong, including ones that shift the blame to another party? Social and political pressure here too can obviously play a role: an assault gets downgraded to disorderly conduct, or a mugging to simple larceny.

Assuming it was classified correctly, the crime is either compiled into a particular aggregate statistic, or not. This process typically involves not just computers or piles of physical paper, but often both, at various stages, with all the worst failures modes of both mediums coming into play. If you work in software, then you already know how susceptible to error such systems are and how frequently mishaps go unnoticed.

Let us call this series of steps the epistemic chain of custody. They are the sequential steps which must occur between an event occurring in the real world and it appearing as doxa, thence to guide policy decisions for Church members. Every step in the epistemic chain of custody is lossy, and every step is subject to perverse incentives on the part its custodians. This is true not only of the process of compiling crime statistics, but in all putatively factual aggregations of numbers. To the extent that trends revealed in the data collected by such a process are meaningful, we assume that it’s because all of the errors are constant year over year, or else that they’re fluctuating more or less at random and cancel each other out. If the process of error accumulation has a persistent bias causing it to drift in the same direction year after year, it undermines the trend analysis altogether, making different years incomparable. Since we’re speculating — if you had to guess, if there were an overall bias in error drift, in which direction would you guess it flowed?

But let us grant that we trust the epistemic chain of custody completely, that we ascribe perfect accuracy to its flow. Even then, we must grapple with whether the chain measures what matters. Remember, the object-level dispute is: is crime getting worse?

The Church has two ways to answer this question: to count the number of crimes recorded by police agencies, and to estimate via survey the number of people who say they have been the victim of a crime. These are the two questions answered by the FBI’s Unified Crime Reporting program (UCR) and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), respectively. I submit that both of these metrics are mismeasures of how a normal person experiences crime, which is a question rooted in gnosis. Specifically, when a normal person ponders whether crime is getting worse, he asks himself, “am I noticing crime more often than I used to?”

If he answers in the affirmative, Church members pounce, explanations at the ready. Perhaps he is consuming media that highlights incidents of crime, making it seem more common than it is, through a sort of false, vicarious gnosis. Perhaps what he’s calling “crime” is just garden-variety disorder (is the man sprawled unconscious at your bus stop bothering you?). Perhaps he is in some way privileged, and patterns of crime have shifted to his demographic when they use to mostly strike the disadvantaged. In other words: there must be some nefarious bias which accounts for the delta between this person’s subjective impression and the true figures, as recorded in the Graphs.

But all of these explanations miss the point about how crime is experienced by normal people, because the true effects of crime are difficult to quantify and therefore turn into Graphs. To understand why, let us consider how a person experiences crime even if they are not, personally, a legible “victim”.

When I walk down my local commercial strip and notice that there is at least one boarded up plate-glass window or door on every block, I am experiencing crime, as are the thousands of my fellow-citizens visiting those same establishments. I wasn’t the victim of the crime, but I’m experiencing its effects, noticing and remembering it. (The NCVS does not include commercial properties.)

When I send my children to a local café to buy some pastry with cash, only for them to be sent home because the stores in my neighborhood no longer accept cash due to break-ins, my children are experiencing crime.

When my wife parks several blocks away from a fitness class to avoid a camp of derelicts doing drugs in the open on the most convenient route, she is experiencing crime.

When my bus stop is littered with refuse including obvious used drug paraphernalia, I’m experiencing crime.

When I enter a drug store and the products are all in locked glass cases, I am experiencing crime. (In fact, you could say I’m experiencing many thousands of crimes at once, their cumulative effect on this part of my life). When the drug store nearest me closes because of security concerns, I’m experiencing crime. Incidentally — if you read that the store pictured below and one in another neighborhood without locked cases were experiencing identical rates of theft, would you conclude that crime was a similarly serious concern in both neighborhoods?

When an aggressively crazy person enters my train compartment and proceeds to shout threats at passengers and the empty air, how many crimes were committed, and how many victims were there? Every person in the train is made to feel wary and upset by the unpredictable and potentially violent behavior of a lunatic. A single such person victimizes potentially thousands of people every day in his sojourn through a city, and yet on a typical day commits no legible crime.

These examples, all of which come from my own life and are related off the top of my head, have one thing in common: the blast radius of the offense is wide and durable, affecting far more people than could ever be included in a victim survey, and for a much longer time than the offense itself. In strict utilitarian terms this kind of crime is probably more impactful than a simple mugging or burglary, which affect a single household more intensely but for a brief duration. The crimes I experience day to day (that weren’t a part of my life a decade ago in the same city) are all this kind of crime. The term “quality of life crime” is apt: their cumulative effect on a block, a transit system, a neighborhood, is to degrade the lives of everyone who encounters their aftermath, the mitigations deployed in their wake. Their cumulative effect is to make us poorer, to make our lives worse.

And although we’ve established by now that the Graphs are missing something essential to our experience of crime, there are a great wealth of them, and they have much to teach us.

Apocrypha

As I said: I’m an apostate, which is much worse than a simple unbeliever. I’m well versed in the teachings of the Church, fluent in their language of charts and figures. And like any good apostate, I have my favorite apocryphal additions to the holy texts. On this topic, they’re not especially hard to come by, so let’s dig into a few of them.

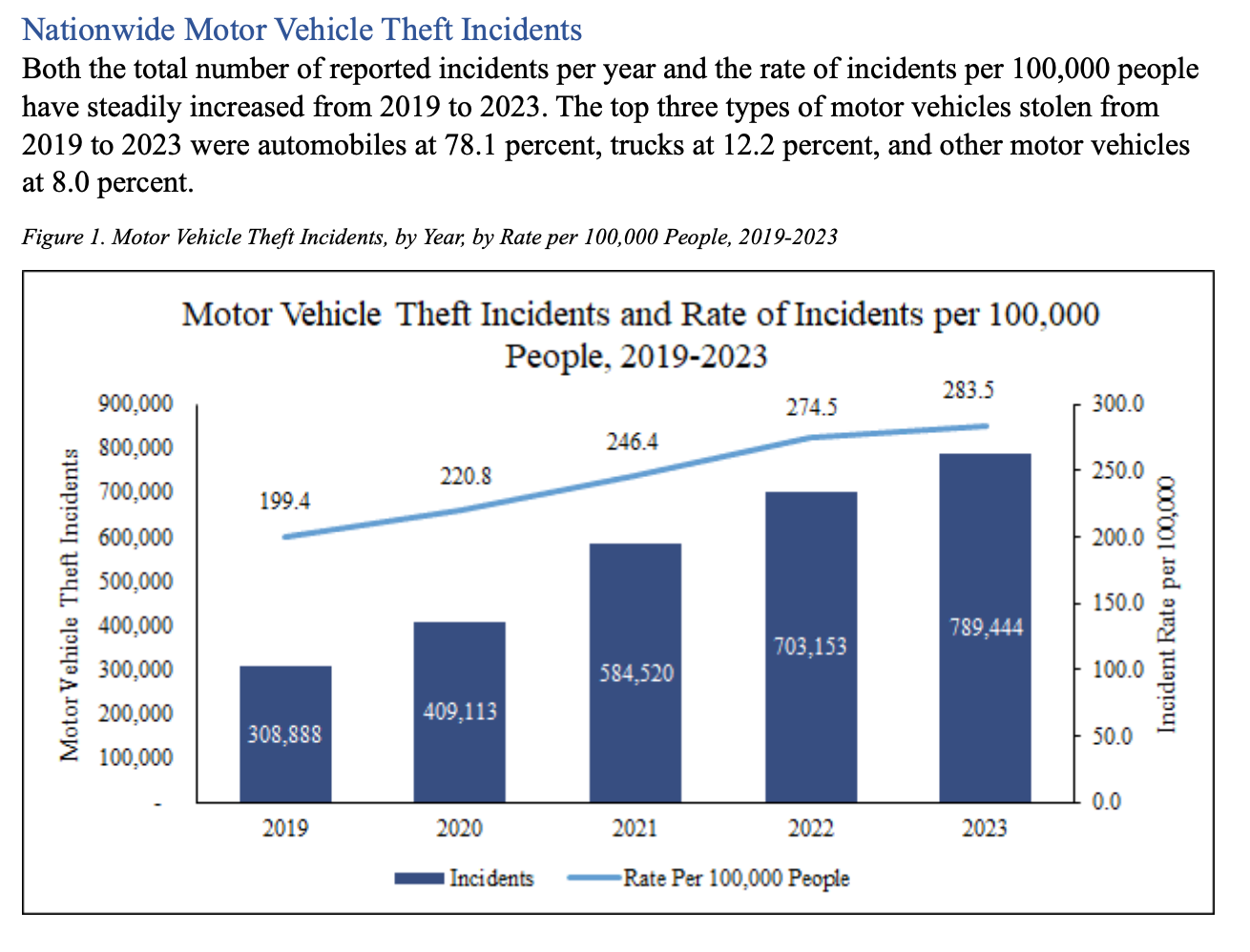

First, vehicle theft. Up nearly 50% in 5 years in per capita terms.

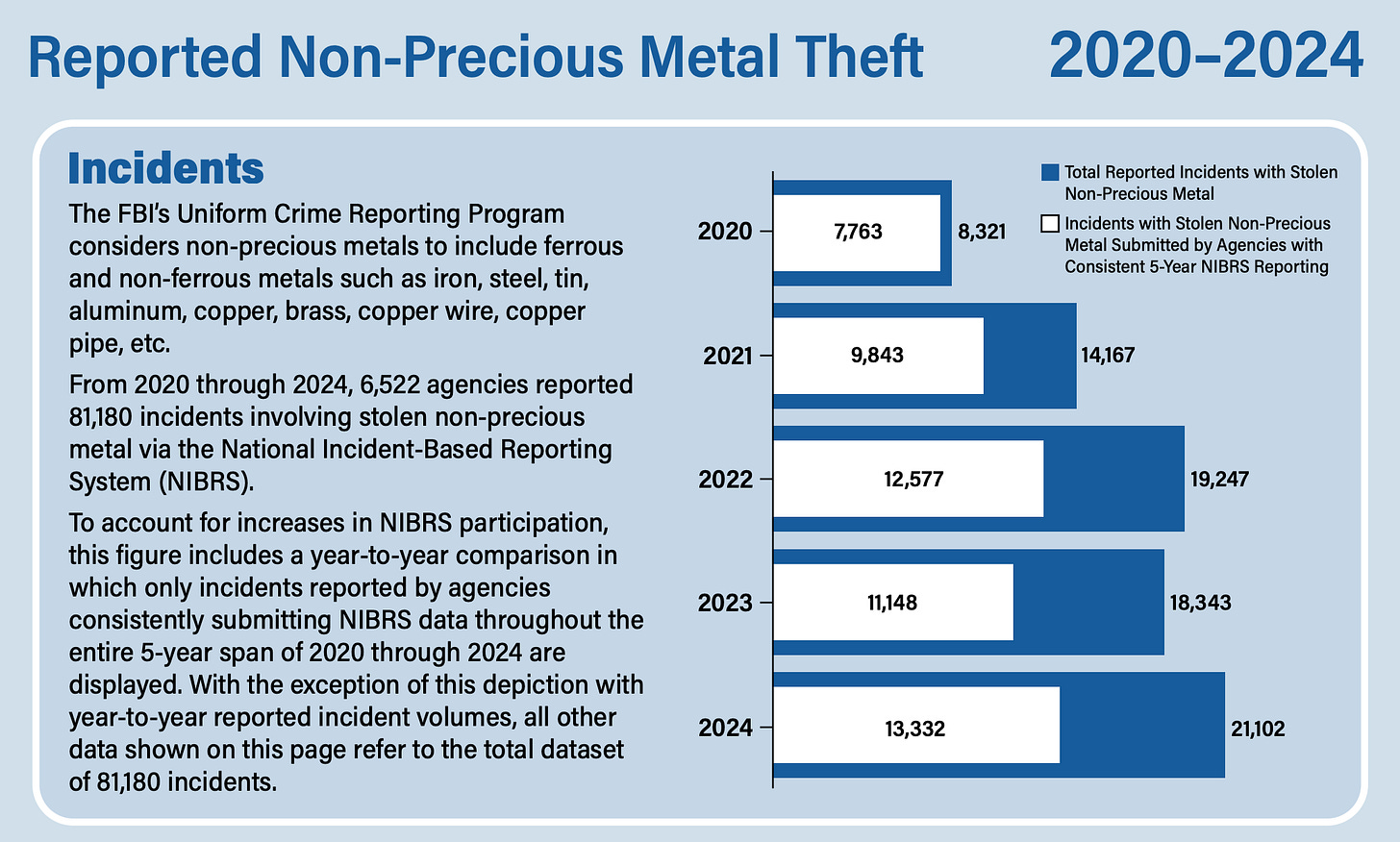

Next, theft of non-precious metals, especially copper. Thieves seem to be increasingly targeting public infrastructure such as street lights or light rail, stealing a few hundred dollars in copper in exchange for tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in repairs and weeks to months of downtime. By the FBI’s reckoning, such crimes have approximately tripled in five years. Note that there’s some confusion in the precise degree of the increase here because the UCR recently changed how participating municipalities and states report crime data, and several of the largest states (CA, NY, FL) have been very slow to adopt the new system.

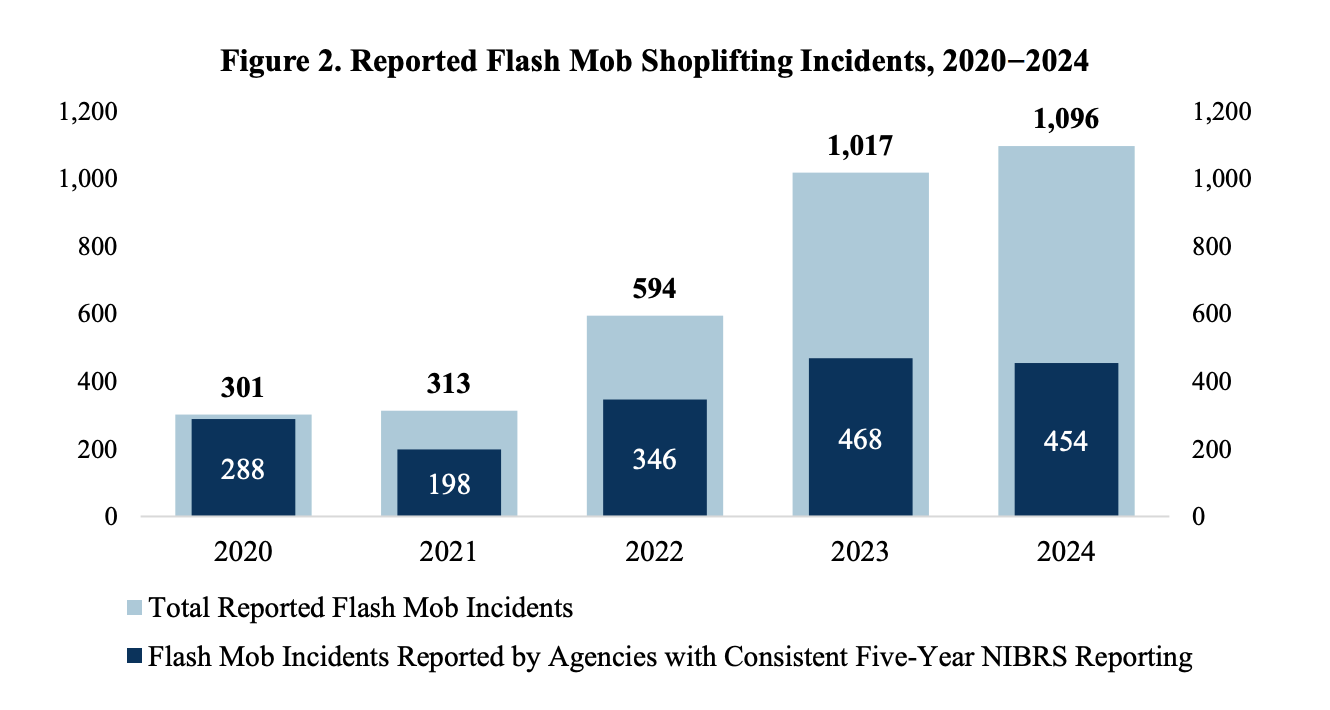

Next, let’s look at two different views of shoplifting. First, here’s another disturbing new criminal trend: flash mobs. These are the mass-shoplifting incidents you may have seen on social media, where gangs of dozens of people, often teens, swarm a store and grab everything they can hold, then run out. This Lululemon store in Houston got hit with 51 shoplifting mobs in six months. Such incidents have tripled in the last five years.

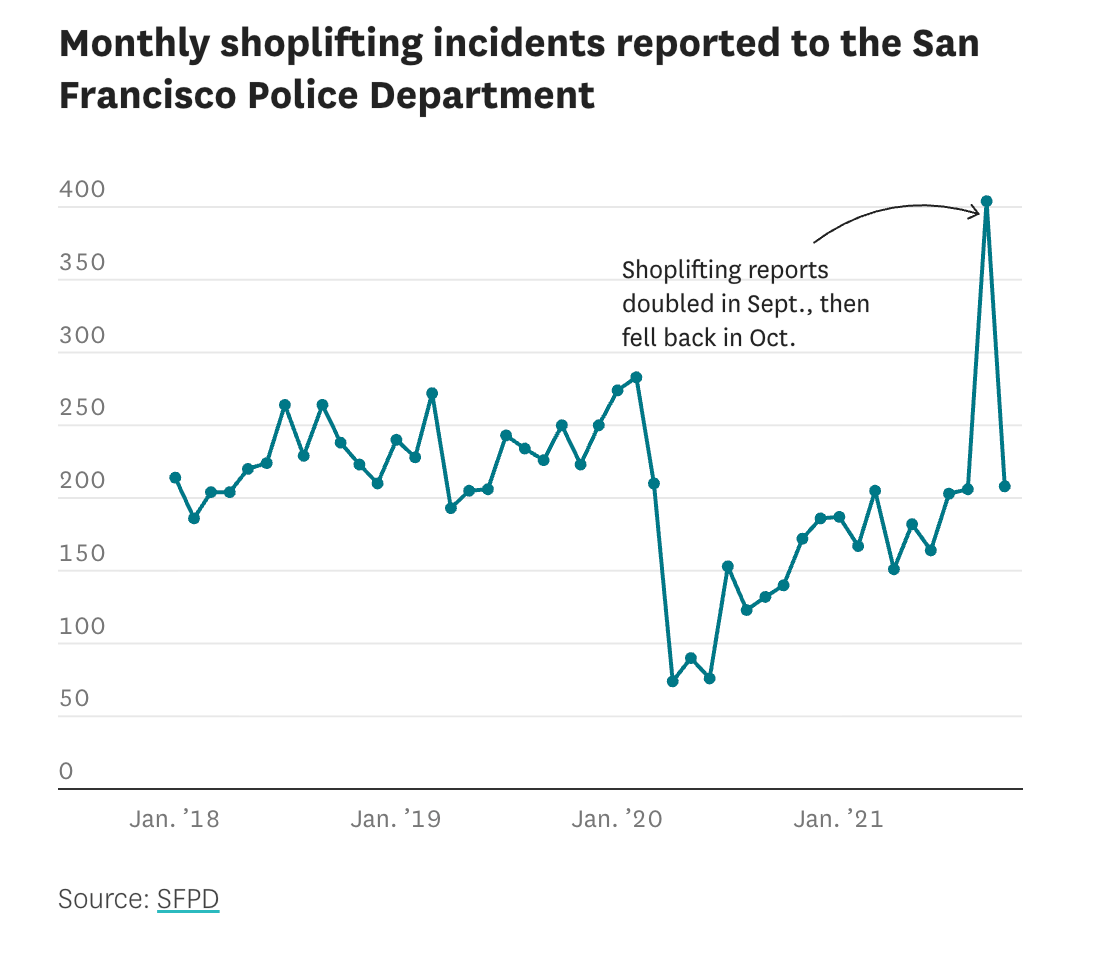

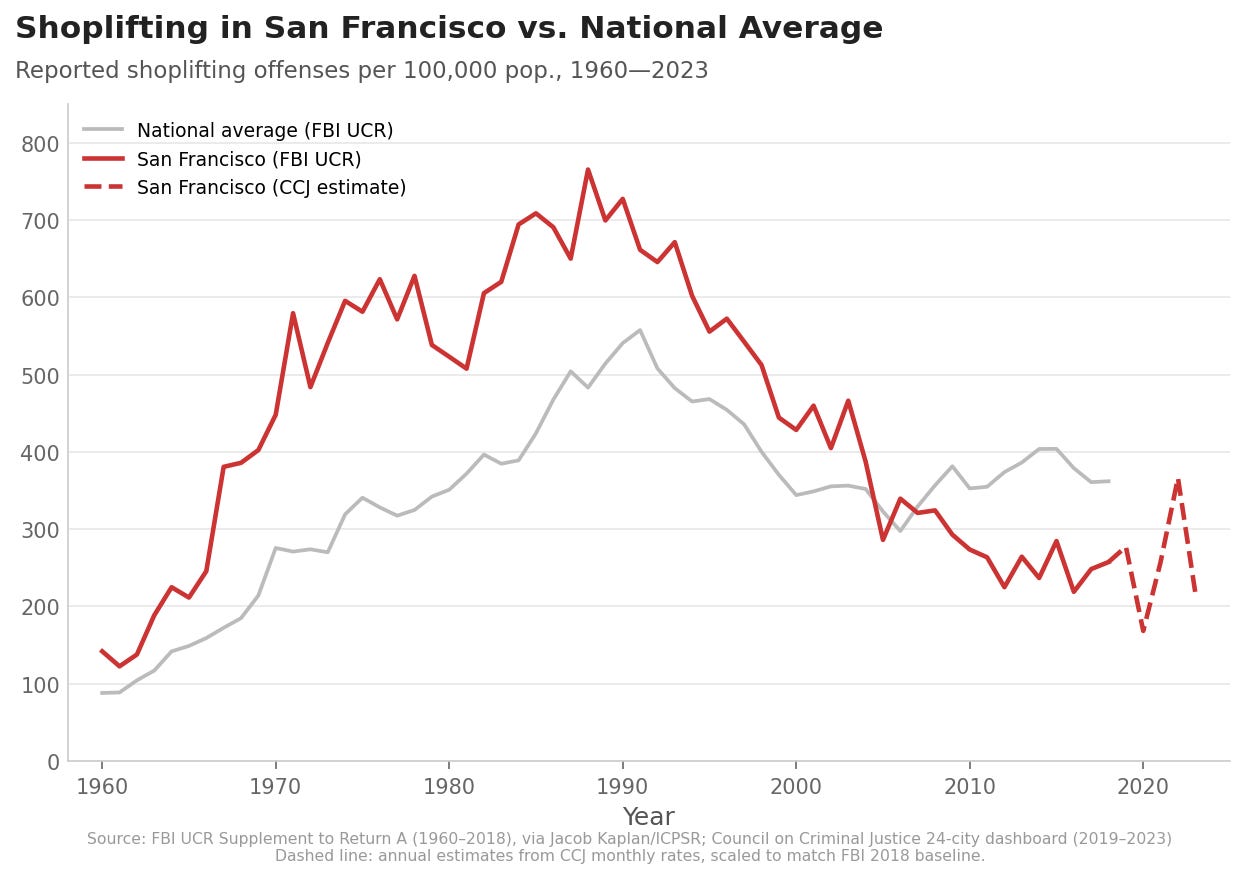

Finally let’s look at shoplifting in Scott’s own San Francisco, where a disproportionate share of his readership also lives. Here’s the official shoplifting rate for San Francisco compared to the national average, lifted from Scott’s post (where he uses it to argue against the idea that shoplifting in SF is getting worse).

Here’s another view of that same data from the SF Chronicle, which we already looked at earlier:

What caused city-wide shoplifting incidents to double for one single month? According to The Chronicle,

A closer look at the data shows that the spike in reported shoplifting came almost entirely from one store: the Target at 789 Mission St. in the Metreon mall. In September alone, 154 shoplifting reports were filed from the South of Market intersection where the Target stands, up from 13 in August. And then, in October, the reports from this intersection went down again to 17.

What happened at this particular Target? Did the store see a huge spike in shoplifting in September? No, said store manager Stacy Abbott. The store was simply using a new reporting system implemented by the police that allows retailers to report crime incidents over the phone.

When asked why the shoplifting reports had decreased again in October, Abbott said she wouldn’t be able to answer any more questions and directed The Chronicle to the Police Department as well as Target’s media team, which did not answer questions either.

So a single Target in a troubled part of town using a more convenient crime reporting system caused the aggregate reports of shoplifting for the entire city to double. This single fact should, by itself, invalidate this entire data set. It’s a bad joke. I will leave the question of why this particular Target stopped using the shiny new phone-based reporting system for shoplifting, and refused to answer questions about it, as an exercise for the reader.

Note that all of these spiking criminal offenses fall into the category of “quality of life” crimes, and further into crimes with broad and lasting impact. A stopped train or darkened overpass, a shuttered store — these are crimes that affect thousands of people, far more than could ever hope to be recorded in the NCVS.

My goal in sharing this apocrypha is not to pit them against the other Graphs in a battle for supremacy. I think all of the graphs in this post, the ones showing crime declining and the ones showing it spiking up, are all approximately as accurate as we could hope. Their accuracy isn’t the problem. The problem is that they tell conflicting narratives that are at odds with one another, and with your own experiences.

Data is not naturally occurring. It does not exist in the white light of pure reason like a mathematical proof. It is compiled by people in service of some goal. And even when that goal is ostensibly completely neutral (the FBI really does want to know how much crime is occurring in the country), the very act of measurement, of quantification, entails judgment and lossy compression. It cannot help but elide essential aspects of the phenomenon being studied. It cannot help but mislead, even when wielded by smart and honest people with the best intentions.

You can believe your eyes

A commenter on Scott’s first post objects:

What would convince you the stats are wrong, or that they are some how not including our lived experience?

I lived in SF from 2007-2013 and again from 2021-2024. The first time the block on Mission between 15th and 16th was normal city block. Now, the entire block is one large illegal market with people selling stolen goods (assuming it hasn’t been cleaned up since 2024). Is that one crime per seller, per day? They’re out in the open, every day. They weren’t there before.

Is this an exception, crime is down over all but just not in SF?

I’m now in LA. There are illegal food stalls over over the place. Some people like them but irrelevant, a crime is being committed, nothing is being done. So every day I see these crimes. They weren’t here 10 years ago. Hence, my experience is crime is up since I visibly see it every time I go out.

When the evidence of your eyes is at odds with the Graphs, and you’re surrounded by serenely smiling Church members, it is a maddening experience. The phrase “gaslighting” is tossed around too often when simple “lying” or “bullshitting” is more appropriate, but in the case of the Church of Graphs it’s apt. Church members gaslight you: they tell you that your own experiences are, if not hallucinations or false memories exactly, unrepresentative. Untrustworthy. Lacking important context. Disqualified from true consideration by the elect.

Aside from this attitude being patronizing and dehumanizing, it’s also simply wrong in most of the ways that matter for your own life. As with many social problems, crime is by its nature hyper-localized, with different cities, or even adjacent blocks in the same city, inhabiting divergent public-safety realities. What does it matter to me to know that crime is getting better (on paper) nationally, or even in my city as a whole? I don’t live nationally, nor in my city as a whole — I live in the particular place that I live, and shop in the particular places that I shop, and I can see those places decaying from year to year.

For that matter, what does it matter to me, as a father and husband, to know that crime was more common in the 1990s? I mostly believe the Graphs on this point, and the older people in my life tell a story that agrees with the data. But my wife and children weren’t being periodically terrorized by street addicts and lunatics in the 1990s, that’s happening to them today, when it wasn’t 10 years ago. The stores are locking up the merchandise and going out of business due to rampant theft today, not in 2016. You can weave a narrative that the 2010s were an uncommonly lawful time in America, and we’re now returning to historic norms, but what good does that do me? My kids need to ride the bus right now, in a city that’s recognizably sketchier than in my relatively recent memories. They don’t get to wait for things to get better.

In one sense, the insistence on high epistemic standards for one’s beliefs about the world is laudable, especially for someone in Scott’s position — he can plausibly direct the course of national policy. One could argue that Scott has a duty as an influential figure to restrict his factual claims to those that can be independently verified and vetted. For him, vibes and gnosis do not cut it. And when it comes to matters of national or regional concern, there are practical limits on gnosis that prevent it from being sufficient to understand the world. I would never claim that facts and figures from third-party accounts beyond one’s personal experiences can be excluded from one’s worldview.

But in another sense, strict insistence on only this formal, quantifiable form of knowledge is itself another kind of bias, an overzealous discounting of forms of evidence that cannot be made to fit cleanly into the Graphs. It’s a blind spot. And Scott would be the first to acknowledge that he is not without his own biases; in fact he is more open and honest about them than any other public intellectual I know. In this case, he prefers a libertarian social policy with fewer people incarcerated or otherwise involuntarily confined. He talks about this at length in his other writing on the topic, and he confirmed his rhetorical goals in a third post in the series, the first two not having convinced his readers:

So I think it’s important to argue that no, crime rates really are down, and it’s not just reporting bias or modern medicine, and that this argument neutralizes a real and influential group of people trying to make the contrary argument that murder/crime rates are up, and to push policy based on that position.

Here I must disagree with Scott in the strongest possible terms: I want to forcibly confine the small number of criminals, street addicts, and lunatics responsible for a wildly disproportionate amount of crime and disorder. Doing so would improve my life and the lives of nearly everyone in my city, including many of those forcibly confined. It would make the world a better place. But my city insists on the right of lunatics and addicts to roam free and unmolested like protected wildlife, and Scott wields his Graphs in service of that same goal. I find this intolerable and will continue to object to it whenever I see it. And I will call foul when I see smart, well-meaning people gaslight their fellow citizens into dismissing the evidence of their senses in favor of figures on paper.

As for me, I’m not fettered by the same standard of notoriety and decorum that Scott is. To my occasional chagrin, I remain a very minor internet microcelebrity in no danger of inadvertently steering the national conversation. Therefore, like animals and proles, I am free: free to establish the epistemic standards that appear to me best suited to understanding the world and my place in it. I am neither a federal court nor a newspaper of record, and permit a certain free-wheeling impulsivity to my judgments as I see fit. Yes, gnosis is limited by definition, and sometimes appears almost useless in understanding the world beyond one’s own horizon of experience. But this isn’t so: gnosis can and must serve as your gut check to the barrage of third-party doxa we are all subjected to on a daily basis. Only the grounding of gnosis can administer the smell-test necessary to separate essential information from fun trivia from malicious propaganda.

And as for your own life, the place you work, the people you know and the place you live: you have eyes. Use them. Don’t let the Church shame you into closing them.