Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition is free for everyone, but I rely exclusively on reader support, so please consider upgrading to a paid subscription for just $4/month to support my work. Alternatively, consider checking out my book FLUKE, which discusses some of these ideas at greater length.

Subscribe now

I: Guinea Pigs with No Control Group

Imagine that two rival scientists announce that they’ve each invented a new miracle medicine. Pop just one pill, they claim, and the likelihood that you’ll get sick in the next unforeseen pandemic—whatever it may be—is drastically reduced. But there’s a problem: nobody knows when the next pandemic will strike, so how can you test whether these miracle pills work or not?

After much bickering, a compromise is reached: each scientist will make their case to the population, giving a rousing speech while trying to convince them that their pill is best. At the end of the debate, the population will vote on which pill to take. Everyone will be required to take a dose of the winning pill—and then wait four years to see what happens. At the end of that four-year period, the scientists will return, again try to persuade the population to take their pill, at which point everyone will either take a second dose or try a different medicine altogether, from a more convincing rival scientist.

Some people will get sick, some won’t, but because everyone is taking the same pill and there’s no control group or rigorous testing—and because nobody knows precisely which illness the pill is supposed to prevent in the first place—it’s unclear whether it “worked” or not. Because of this uncertainty, people start to sort themselves into medicinal tribes, voraciously consuming news that affirms their belief in their favored pill. Amidst all this pharmaceutical chaos, there does seem to be one clear pattern in this strange society: if it “feels” like a lot of people happen to be sick at the end of the four-year period, then the population will try a different pill.

Surely, nobody would agree to this absurd strategy. Year after year, citizens would be guinea pigs, but without every getting closer to discovering what medicine works and what doesn’t. After all, few would willingly take a vaccine based solely on a scientist’s ideology that it should work or decide which medicines to take based on how silver-tongued a doctor might be.

And yet, this is exactly how we run society. Instead of rival scientists, we turn over humanity’s most important decisions to ideologue politicians who simply debate what to do with the economy, health care, war, poverty, immigration, and climate change based on what they think might work. Then, after four years, in an infinitely complex world in which a million variables change, nothing is held constant, and there are no control groups, we subjectively decide whether it worked. If enough people think it didn’t, we collectively decide that we’d like to follow a different ideologue’s plan instead.

This is, quite clearly, insane.

The remedy to the insanity of ideology-based guesswork, as we’ve figured out with scientific research such as medicine trials, is rigorous testing that definitively proves what works and what doesn’t. With social research, for reasons we shall soon explore, that approach is often impossible. Studying human society is never so simple. After all, eight billion interacting human brains are, without question, the most complex entity in the known universe.

No matter how much we try, understanding ourselves proves elusive. The chaos of human society is shrouded in unpartable clouds of mystery.

So, what we do instead is this: we put a lot of clever people into universities, where disproportionately elbow-patched boffins come up with sophisticated theories and arcane models that provide better guesses about what will and will not work based on past patterns. They toil endlessly, trying to get slightly better at understanding a social world that is impossible to understand. When one of them comes up with a theory that seems pretty good at describing what happened in the past, they take it to an annual gathering of other boffins who scratch their chins, ask rude questions, and then retire to their hotel rooms.

Subsequently, the theory might get published in a journal so expensive that normal people can’t access it. The research will be read by a small number of other clever people in universities, at which point the ideologues governing society will diligently fail to read about the evidence or pay any attention to it unless it confirms what they already believed about the world. If the theory and the evidence happen to conform to their prevailing ideology, they will then enthusiastically embrace the findings after reading a staffer’s summary. The politician will then show their appreciation for the research by misrepresenting it to the public.

Shockingly, this seemingly foolproof strategy appears to not be working.

I am a disillusioned social scientist, critical of my own discipline, but eminently aware that fully understanding human behavior is a nearly impossible task. As I wrote in Fluke, we’re making a mistake when we use the phrase “it’s not rocket science.” We should be saying “it’s not social science”:

“In 2004, humans launched a spacecraft that traveled for ten years before softly touching down on a comet two and a half miles wide that was traveling at eighty-four thousand miles per hour. Every calculation had to be perfect—and it was. Conversely, trying to figure out, with certainty, whether Thailand’s economy will grow or contract in the next six months or whether inflation in Britain will be above 5 percent three years from now, well, that’s just not something we can do.”

Sometimes, despite an astonishingly abysmal track record, we keep using the same tired, failed tools to try to decide what to do. Aside from the ridiculousness of turning to the same pundits, no matter whether they’ve been prescient or grotesquely wrong, we continue to double-down on failed methods of social research and forecasting. In 2016, The Economist magazine conducted an analysis of IMF economic forecasts that covered 189 countries over a period of fifteen years. During that time, a country entered a recession 220 times. How many times did the IMF April forecasts correctly predict the recession? Zero.

Part of the source of this trouble is a straightforward issue that’s extremely difficult to solve. I call it the Problem of Zombie Research—in which bad theories never die. That problem, alas, is endemic to the social sciences.

The economists Wynne Godley and David Evans summed up the issue:

Evans: What actually does resolve disputes in economics?

Godley: Nothing!

Evans: They just go on…well they certainly seem to.

Godley: Successful rhetoric is what resolves issues.

Like the people in the absurdist pill-popping society imagined above, we are largely unable to falsify proposed explanations about how our world works. We therefore find ourselves unable to definitively prove which theories are golden and which are garbage. And when that happens, social science can sometimes end up becoming a caricature of itself, in which clever people play with increasingly sophisticated models but don’t provide a roadmap to solving real-world problems.

We need good social science. It is the only tool we have to make the world better based on evidence rather than ideology. But to escape the absurdism of our current situation, we must do two things better:

Be ruthlessly clear about what social science is for (solving problems to mitigate avoidable harm, not just identifying an elegant single causal explanation for past variation in flawed data).

Get better at slaying Zombie Theories by making (often wrong) predictions.

II: The Easy Problem of Social Research

A little over a decade ago, a renowned researcher named Daryl Bem produced compelling evidence that he had discovered proof of extrasensory perception, or ESP. His findings, which passed peer review and standard methodology checks, were published in a top psychology journal.

But when some other researchers thought that Bem’s findings didn’t pass the smell test, they took matters into their own hands: they tried to replicate his findings by repeating his experiments.

They couldn’t. The findings were bogus—statistical correlations that “discovered” a phantom effect with no basis in empirical reality. But when the scientists exposing Bem’s studies tried to get their findings published to expose the bad research on precognition, nobody wanted to publish an article that was re-treading on old ground. Worse still, one of their journal rejections came after a peer reviewer trashed the replication studies. That reviewer’s name? Daryl Bem.

Eventually, Bem’s findings were thoroughly debunked. This saga, fueled by other high-profile examples of bogus research such as the viral “power pose” studies, launched the replication crisis, in which it soon became clear that many significant findings in social research (and some in medicine) could not be reproduced in subsequent repeats that used the same methodologies.

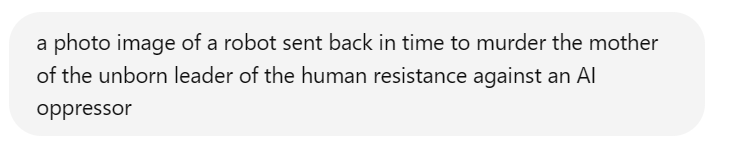

There are many reasons for these well-known crises of confidence in social research, including p-hacking, the file drawer problem, the McNamara Fallacy, measurement error, category mistakes, and manipulated or invented data, to name but a few. There are also serious concerns with the peer review process, which often fails to catch even the most egregious errors. (One study deliberately planted serious flaws in research papers and then sent them out for peer review. Reviewers, on average, detected only 2.6 out of 9 serious planted mistakes).

All of these problems deserve serious attention, but they are extremely fixable. They are basically implementation problems, which do not pose any philosophical challenges to what we can and cannot know about our world. That’s why I bunch them together and refer to them collectively as forming The Easy Problem of Social Research. With better methods, shrewd adjustments to detect manipulated research, and peer review reform, these problems can be solved—and some bogus theories can be killed off.

But there’s a deeper crisis being ignored—one that’s more fundamental to the nature of what we can and cannot know about human society.

III: The Hard Problem of Social Research

In 2022, a brilliant study was published that should have rocked the foundations of social science to their core—triggering a much more profound research crisis.

A team of researchers led by Nate Breznau decided to tackle a thorny question that plagues modern politics: do higher levels of immigration reduce public support for social safety net programs? Let’s consider three hypotheses:

Because of xenophobia, more immigrants mean that native-born citizens will decrease support for tax dollars spent on social safety net programs.

Because of social generosity, higher immigration will increase support for social safety net programs to help integrate the less fortunate.

Immigration won’t really affect support for social spending much either way.

This question is both interesting and important; a definitive answer would help inform public policy debates across the democratic world. So, which is correct?

To find out, Breznau and his colleagues did something clever: they asked for a large number of volunteer research teams to try to answer the question as best they could using the exact same data. In total, 161 social scientists working on 73 independent research teams did their best to try to find the “right” answer to this seemingly straightforward question.

What happened next should bewilder every social scientist—and the public—and it was far bigger than any question about immigration.

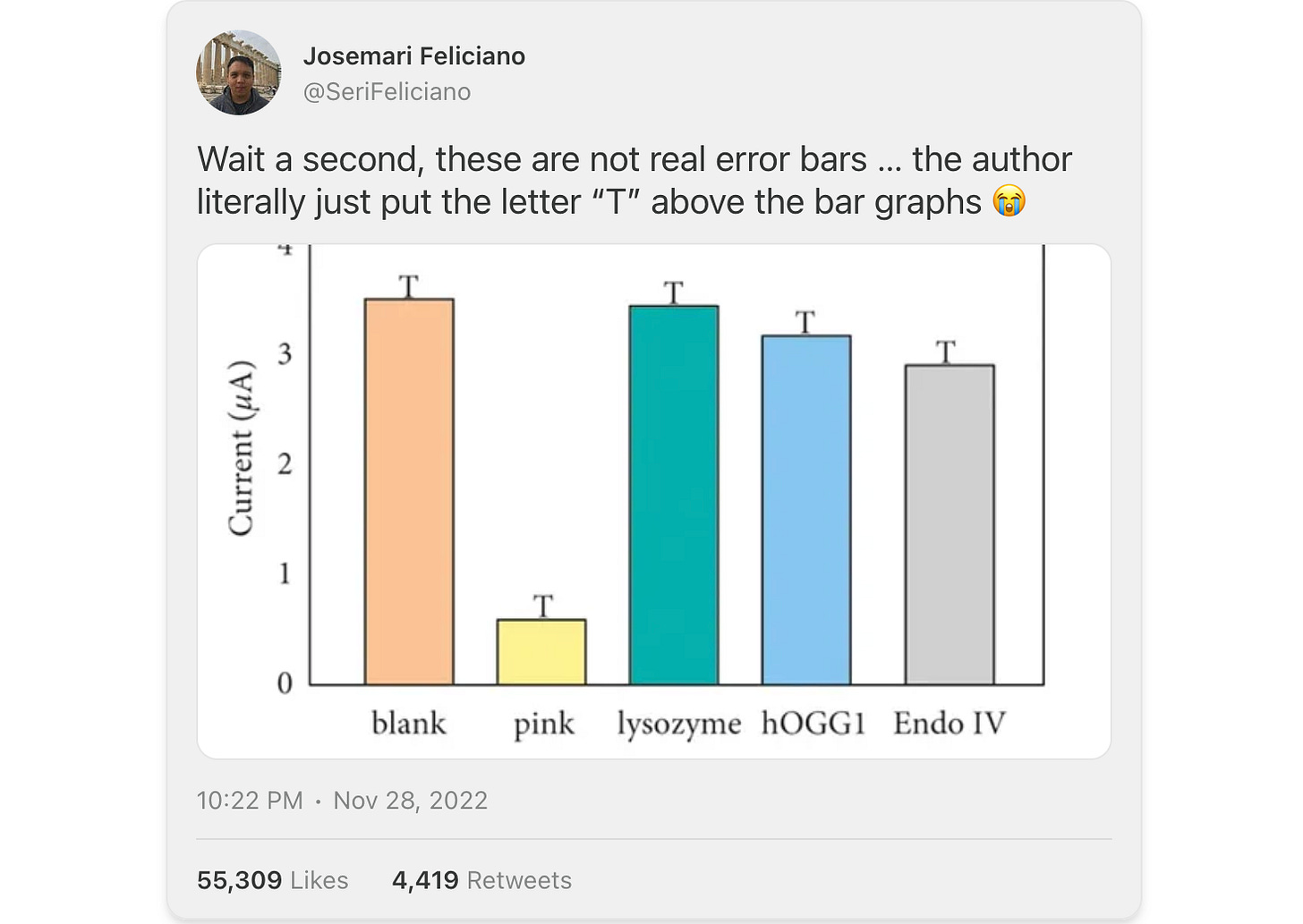

The 73 teams produced a completely mixed result. A little over half of the teams found no effect—that immigration levels didn’t seem to move the needle much in either direction. About a quarter of the research teams found a significant negative effect. And just under a fifth of the research teams found a significant positive effect. The results, absurdly, followed a somewhat normal distribution.

Breznau’s team controlled for virtually everything: they gave the research teams the same data, the same question, and made all the research teams catalogue every methodological decision. Despite those commonalities, tiny, seemingly insignificant choices led to wildly different findings.

Poring over the various findings, Breznau’s team could only figure out what contributed to five percent of the variation between the research teams; the other 95 percent was inexplicable. As they put it, fittingly flummoxed by the results: “Even the most seemingly minute [methodological] decisions could drive results in different directions; and only awareness of these minutiae could lead to productive theoretical discussions or empirical tests of their legitimacy.”

They billed the problem appropriately: we live in a universe of uncertainty. Such unresolvable uncertainty is an epistemological challenge to what it is possible to definitively know about our social world, what I call The Hard Problem of Social Research.

Here’s why it’s a big problem: for 99.9 percent of social science studies, there are not 73 research teams working on the same question with the same data. Instead, one researcher takes their best shot at a problem and comes up with their best answer. In those situations, the researcher gets to decide what question to ask, which data to use, how to measure phenomena of interest, how to categorize variables, what data analysis strategy fits best, which results to report, and how to frame a finding.

If Breznau’s team had asked only one research team to answer the immigration question, there would be a nearly equal chance that they would find either that higher immigration increased support for social spending or decreased it. Once published, either a positive or a negative result might be considered a settled question. The irreducible uncertainty would be hidden from view.

This raises the unsettling follow-up question: how many seemingly “solid” past social science research findings would be more like the universe of uncertainty debacle if they were farmed out to 73 separate research teams? Nobody knows.

This is a much bigger problem than the replication crisis. It challenges the most basic assumptions of social research.

The astonishing variance in the “Universe of Uncertainty” paper also points to the core dilemma raised above: how do you definitively reject social theories in a world that is infinitely complex and therefore so difficult to accurately study? In physics or chemistry, if a predicted result is off by a millionth of a percentage point, the entire theory can be rejected outright. Perfect precision is required.

But in social research, if a model is able to “explain,” say, 60 percent of the variation in the data, then it’s considered an incredibly strong result. That’s because the social complexity of billions of interacting, self-aware, conscious human agents embedded in ever-changing social systems is far harder to model than even the most unruly molecules. Precision is impossible.

Worse still, unlike with molecules, social research is fragile and context-dependent. If a caveman anywhere in the world mixed baking soda and vinegar together, it would fizz at precisely the same rate as today. But if the exact same virus that sparked the covid-19 pandemic had infected someone in 1990 instead of 2020, everything would have been different. In 1990, China was less connected to the world. George H.W. Bush, not Donald Trump, would have handled the US response. And most crucially, without widespread digital technology, working from home would have been impossible, so the economic effect of an identical virus would have been radically different. In social research, everything matters.

Moreover, with probability estimates, it’s extremely difficult to verify theories with one-shot events. Claiming that X makes Y more likely isn’t possible to prove or disprove if an event only happens one time, but many of the most important events are one-offs. Nate Silver’s claim that Hillary Clinton had a 71.4 percent chance of victory in 2016 could never be proven “wrong,” because when she lost, Silver could just say that the less likely outcome occurred.

The upshot is this: because the world is so maddeningly complex and because our models are so imprecise as a result, there’s plenty of latitude for researchers, politicians, and the public to pick and choose their preferred theories. Choose your own social science explanation!

This dynamic differs from “hard” science. Only delusional crackpots think that the sun revolves around the Earth, but after decades of research and mountains of evidence, there’s still no unequivocal agreement about the precise economic effect of cutting taxes on the rich. And that’s with a question that’s actually pretty clear-cut when it comes to the available evidence! (Hint: tax cuts for the rich mainly benefit the rich and don’t “trickle down”). But most social research on the biggest questions we face doesn’t produce such clear-cut, consistent answers.

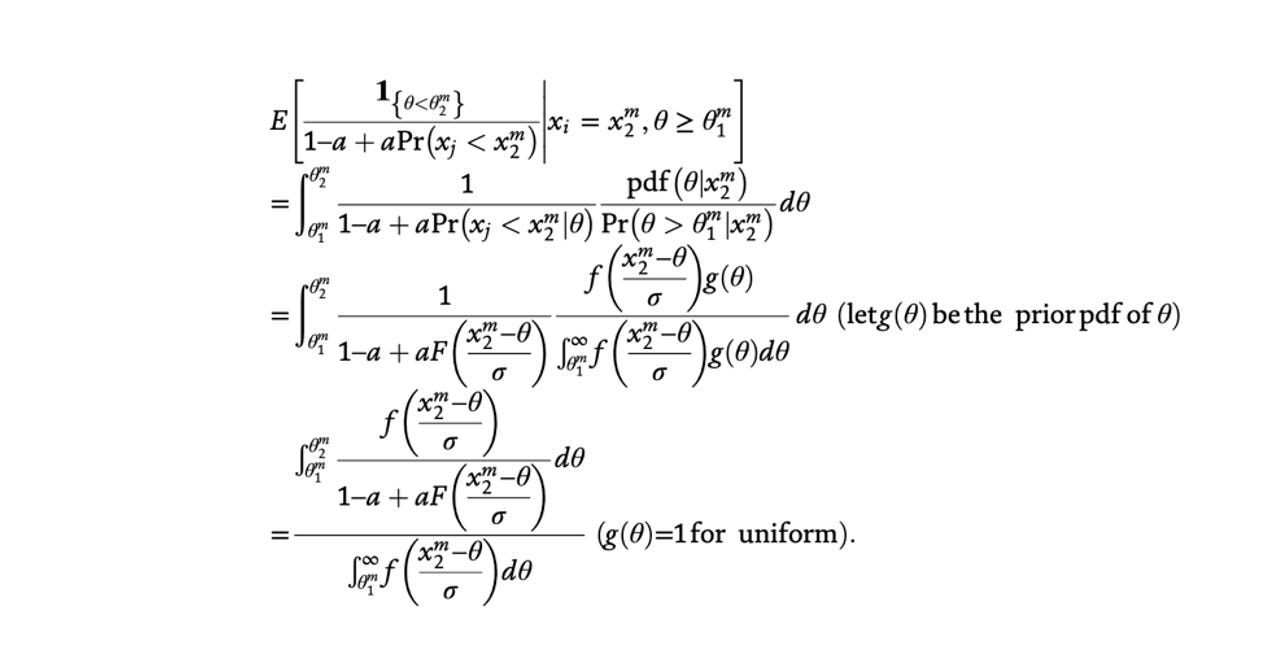

One of the more recent strategies to parry these critiques has been to dress up the flaws, adorning some deeply uncertain dynamics with really sophisticated looking model garb, in the hope that nobody notices because the equation looks really impressive and precise. These are what I call The Emperor’s New Equations. For example, as I highlighted in Fluke, here’s an actual equation from a recent unnamed political science paper that gives the exact mathematical formula for whether a given person will join a rebel movement during a civil war:

And yet, when the boffins get together to scratch their chins and exchange equations like these on PowerPoint slides, everyone is afraid to say what’s obvious. So, I’ll bite the bullet and be the bad guy here:

This is all, quite clearly, silly.

IV: The Case for (Bad) Predictions

So, how good are we currently at predicting social outcomes? Consider the Fragile Families study, which tracked five thousand families, each with a child born to unmarried parents. Data about the children was collected at ages one, three, five, nine, fifteen, and twenty-two, making the study one of the richest collections of rigorous, detailed data ever conducted. Then, as I wrote previously:

“After the data from the children who had turned fifteen was collected, it wasn’t released. Instead, the researchers held a competition, in which they gave competing teams of scientists access to the data from the children at ages one, three, five, and nine. The challenge was to see who could best predict life outcomes for the children now that they were fifteen years old. Because the researchers already had the real-world outcomes, they could see how well the teams had done relative to reality. The teams used machine learning, the most powerful data analysis tool ever invented, and took their best shot.”

All of the teams failed miserably. Even the best performing research teams performed about as well as a model that just followed simple averages. The sophisticated models were basically useless.

This was a wake-up call: these problems are not just going to be easily solved by more advanced technologies like AI. However, by making predictions and failing, this study provided a catalyst to refine our theories. If the researchers had only fit their models to past data, they might have looked like they had done a great job at explaining what was going on. But by making a forward-looking prediction, the limits of our understanding become clear—which will force us to improve.

Alas, predictions are currently an endangered species in social science. Mark Verhagen of Oxford found predictions in just 12 out of 2,414 (0.4%) articles in the top economics journal; in 4 out of 743 (0.5%) articles in the top political science journal, and in 0 out of 394 articles in the top sociology journal.

With quantum mechanics, physicists don’t fully understand what’s going on, but they can make extremely accurate predictions that have proven extraordinarily useful for solving real-world problems. With social science, there’s a risk that many of our models are the worst of both worlds: not being able to fully explain what’s going on and being unable to predict what will and won’t work to solve real-world problems. But with most economics or political science or sociology research, we’re not really interested in the mysteries of the fundamental nature of reality. We should mostly care about what works best to mitigate avoidable harm.

That’s why I favor a paradigm shift in social science toward making more explicit predictions. Most of them will be comically wrong, but by making incorrect predictions, we will iteratively get better at navigating our world—and slowly improve at finally slaying bad Zombie Theories that stubbornly refused to die.

V: Strong Links and Weak Links

Many social phenomena can be sorted into two categories: “strong link problems” and “weak link problems.”

As the always insightful points out, food safety is an example of a weak link problem, in which you have to worry about the weakest link. Even if 99.9 percent of a country’s food supply is free of toxic bacteria, the 0.1 percent can imperil everyone. A rowing crew is also a weak link problem: if seven rowers are Olympians but one scrawny rower is out of sync, the boat will slow to a crawl.

Strong link problems are the opposite: everything will be fine as long as the strongest link is really strong. Basketball, unlike rowing, is a strong link problem. LeBron James is good enough that even if there’s a really weak player on the bench, the Lakers are still going to win a lot. And, as Mastroianni convincingly argues, science is a strong link problem. It’s okay if there’s a lot of junk science out there being published in pseudoscience journals, because the strongest discoveries that change the world are what matter most. Pay attention to the best science, ignore the worst.

I see an exception to Mastroianni’s argument. Zombie Theories in social science short-circuit these dynamics. For the reasons mentioned above, it’s rarely universally agreed what the strongest links actually are in economics, political science, psychology, or sociology. Without being able to kill off the bad but influential theories through falsification, what should be a strong-link problem ends up just being a bit of a mess, with bad ideas lingering on, often obscuring better ones.

Don’t get me wrong: there’s a lot of astonishingly good social science research. I’m often in awe of colleagues across disciplines who have devoted their lives to solving problems in the most innovative ways. My critique is not that social science is useless, but that it could be better.

Yet, in order to stop the madness of our current social trajectory, social scientists need to take these profound epistemological challenges more seriously and develop a laser-like focus on finding better ways to guide policymaking more reliably. Sophisticated models with impressive equations, clever research designs, and robust statistical significance make careers, but unless they help us navigate a perilous world and mitigate avoidable harm, what’s the point?

We need good social science now more than ever. The world has never been more complex or dangerous, a tangle of unprecedented instant interconnectivity, laced with at least three existential risks: nuclear weapons, artificial intelligence, and environmental collapse. Every risk is amplified by overconfident authoritarian fools in power. Our capability to destroy the world has outpaced our wisdom to understand and govern ourselves—and that’s why we need every shred of evidence-based sagacity we can muster to forge a more resilient, just world.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This essay was for everyone, but if you found it interesting or worthwhile and want to support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription for just $4/month. Alternatively, to more deeply explore my ideas about chaos theory, complexity, and the role of chance in our world, buy a copy of FLUKE, which was twice-named a “best book of 2024.”

Subscribe now

Share

![r/dataisbeautiful - [OC] The Highest-Grossing Media Franchises Of All Time r/dataisbeautiful - [OC] The Highest-Grossing Media Franchises Of All Time](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fda52f1be-4703-4aee-acd9-3c3876ee6dd2_1080x1080.png)