According to my records, between 2008 and 2013 I assigned ’s essay “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” (first published in The Atlantic August 15, 2008) to 14 different sections of college writing students.

In the essay Carr wrestles with what he perceives as a change to his own ability to pay sustained attention to reading and thinking because of the way he’s found himself working with and on the Internet. He sums things up this way, “My mind now expects to take in information the way the net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”

He extends from his experiences to the experiences of others, reporting on what he’s heard from friends and colleagues, or what he’s read by other contemporaries. He goes deeper on the connection by technology and cognition and argues that we are now digital Taylorists (after Fredrick Winslow Taylor who studied automation and efficiency in industrial settings), where the system dictates the human’s behavior, rather than the other way around.

He shares a quote from Google co-founder Sergey Brin that hits particularly hard in today’s era of generative AI, seventeen years on from Carr’s writing, “Certainly if you had all the world’s information directly attached to your brain, or an artificial brain that was smarter than your brain, you’d be better off.”

In 2008, Carr writes that this “easy assumption that we’d all ‘be better off’ if our brains were supplemented, or even replaced, by an artificial intelligence is unsettling.” I was generally sympathetic to Carr’s argument from the first time I read it, but at the time of teaching the essay, I was much less unsettled than him, and speaking as someone today who finds himself significantly more unsettled now, I’m wondering why.

Some of it is age and time. It was seventeen years ago. I was younger and had seen and experienced less. My lens did not have the same length and breadth as Nicolas Carr’s. I also had not experienced the same kind of disruption to my reading abilities that Carr describes. The Jet Ski versus scuba metaphor made sense to me, but at the time (and indeed, to this very day), I felt very comfortable toggling between scubaing and jetskiing. I think a lot of this is due to the sweet spot of my age where I’d established those root skills of deep reading (c.f. Maryanne Wolf), and was also very quickly comfortable with the affordances of the internet, while always being able to distinguish between the two modes.

The Internet had also been a huge boon to my career, giving me access to outlets for my work that never would’ve been on offer in the earlier eras that Carr had come up through. I was good at delivering quick, timely bits. At the time I was editing the McSweeney’s website and the way the submission inbox filled with good (and not good) stuff from all over the world suggested to me that all this connectivity and speed was on balance a good thing, not necessarily an advancement, but not a retreat. I was aware of the risks, but I was much more hopeful about the upside.

Do you know who else was less hopeful about the upside of the access and connectivity afforded by the Internet?

My students.

Every semester one of the first things I had to discern was my students’ abilities to properly identify another writer’s argument and “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” was a perfect vehicle for that assessment.

It’s written at a sophisticated level, but targets a general reader requiring no knowledge of specialized jargon or academic concepts.

It explores an experience familiar to students, accessing and reading information online and being expected to work with that information in academic contexts like writing and research.

It’s personal, but also reaches out to draw in outside sources and ideas, connecting Carr’s sense of a changing world with the ideas and experiences of others. In fact, I said that our end of semester goal was for everyone to be able to write something very much like “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” only about a subject of their own interest and told from their unique perspective.

The opening gave me an immediate opportunity to check how actively students were reading.

In class I would read that opening paragraph aloud, then pause, and ask students how many of them truly knew what he was referring to. In a class of 25, no more than two or three students had seen the movie, and many had never even heard of it. I asked how many were confused (definitely some). I asked how many used the miracle of Google to better inform themselves about the film and context (zero). I asked them why not and they shrugged. It hadn’t occurred to them. I’d then show the clip, easily found on YouTube.

I asked what the choice of reference might tell us about who Carr is targeting as his audience, and pretty quickly they’d figure out that it was directly intended more for people my age (or even a bit older) than their generation, which was more native to life online.

I asked them to give me a reference that would better connect to people of their generation, and the near universal answer was a movie called Smart House, which apparently aired on the Disney Channel on a weekly basis through most of the 2000s that I still have never seen.

Above all, I wanted them to understand that reading in the way that I expected was not passive, and they would know they’re doing it “right” if their mind was conjuring questions and connections as they moved through the text.

This level of attention was largely unfamiliar to my very bright, well-prepared students because the nature of what they’d previously been asked to do with texts had little relationship with what I was trying to model. They been able to get by with a general passing familiarity with what they’d read because very rarely, if ever, had they been asked to make something from someone else’s text.

In fact, many struggled significantly with the basic purpose of the writing portion of the exercise, to accurately summarize Carr’s argument.

The overwhelming majority of my students would summarize the piece’s content, e.g. “Nicolas Carr writes about how the Internet is changing our brains,” rather than zeroing in on specifically what Carr believed about how the Internet was changing our brains.

Discussion revealed that my students were, in fact, worried about their brains, increasingly so as the years advanced, particularly with the advent of Instagram in 2010, a platform that many of them felt a kind of compulsion toward. This was a step beyond Carr’s notion that we were becoming overused to skimming text. This was endless, mindless scrolling through images.

At the same time, one of the byproducts of reading and discussing/writing about “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” was students acknowledging that they had at least some measure of agency over the technology and how they used it. Building this agency became a kind of sub rosa purpose of the course as the temptations of being online interfered with their ability to complete their assignments in our writing course. This was the period of time where I was actively developing what would become my framework of “the writer’s practice” and it was a student who first posited that one of the chief skills of a writer is “concentration.”

“How many of you have a hard time concentrating?” I’d ask. Every hand was raised.

I’d taken my ability to concentrate for granted, but my students were telling me that this was something they needed to work on, and so we did, more so with each passing year as I developed some very specific writing experiences and suggestions for drafting that privileged connection and slowing down over speed and efficiency. I wanted students to experience the pleasure of noticing something about yourself in the world and then bringing that noticing to life in a way that connects with others, of making connections in the way Carr does in the essay.

One of the other things I’d ask students to do after we’d discussed the essay’s meaning is to list out all of the sources that Carr apparently draws from in the completion of this relatively short piece of writing. We’d go paragraph by paragraph and the list would be dozens of different sources long. They were amazed. I wanted students to appreciate the density of the piece and suggested that over time, they could and should strive for something similar, while acknowledging that the benefit of time and experience made this easier to achieve.

“If you start paying attention now, you can learn a lot of stuff,” I’d tell them.

I’d tell students this because I’d reached the part of my career where I was starting to see the benefits of my own learning. I was also frank with them by admitting that when I was in college, I failed to take advantage of all the opportunities I’d been given to learn stuff.

One additional reason I was somewhat less alarmed than Carr is that my experiences as an instructor of introductory college writing caused me to believe that the thing we are fighting for is the preservation and implementation of human agency, and that if we worked carefully and collectively this ability could be fostered, and once fostered, it would endure. I’d seen it happen for hundreds of students moving through my classes over the years.

Yes, Google could make us stupid, but it didn’t have to. It wasn’t inevitable. This is what I wanted students to believe, and furthermore I wanted them to believe that reading and writing were great defenses from becoming stupid. This is the same mentality that led me to declare that ChatGPT can’t kill anything worth preserving at the time of its initial appearance.

I still believe this! We do have the power inside ourselves to resist the negative byproducts of working with large language models should we choose to do so. I suppose much of my work now is trying to help other college faculty demonstrate the value of resistance where resistance is warranted.

While I still believe this is possible for individuals, and will keep working to foster the conditions that allow for individuals to choose agency over automation, I am much less confident that sufficient numbers of people will be able to resist the pull of the platforms and effects of this wave of AI technology.

I’m not quite ready to give into the Borg and declare resistance futile, but resistance is very very hard, and the stakes are higher than ever. Nicolas Carr’s most recent book, Superbloom: How Technologies Tear Us Apart, is a helpful look at why these things are indeed so hard.

There is a lot to the book, and its worth grappling with all of its facets in detail, but in essence, it is about how the intersection between these platforms and our human vulnerabilities makes for an bad mix. Carr argues that we have made an online world in which it is near impossible for the human psyche to survive intact.

Even though this is not my experience,1 I can’t deny that this may be true for many if not most. Consider the increasing number of people who are lapsing into literal psychosis when interacting with chatbots. These reports are beyond unsettling. Also consider the apparent terminally online state of the killer of Charlie Kirk, a young man steeped in memes and online culture who decided ending a life the most violent and public fashion imaginable was somehow sensible.

Social media is not de facto bad for you, video games do not make you violent, using generative AI doesn’t inexorably lead to a diminution in one’s ability to think for themselves.

And yet, many people are psychologically harmed by being on social media. Playing video games does not lead to violence, but there is a burgeoning online “gaming” culture that is increasingly linked to public shooters. I wrote about the way laborers are damaging their ability to do their work in the absence of the algorithmic help just a couple weeks ago.

The deep question that I think we have to continue to wrestle with - and I appreciate any reader thoughts on this - is: How do we steel ourselves against how these platforms and technologies are indeed designed in ways that not just could, but will harm us?

Links

At the Chicago Tribune I covered Nicolas Boggs’s amazing biography of James Baldwin, Baldwin: A Love Story.

I took two different looks at the recent purging of a Texas A&M instructor who was fired despite displaying the highest levels of professionalism when targeted by a student. For the I covered the big-picture implications for academic freedom. At Inside Higher Ed I identified the student’s actions as an act of madness and wonder how it’s possible to teach and learn in this kind of atmosphere.

The longlists for the National Book Award were announced.

Please enjoy this reflection on how legendary editor Dan Menaker put him on the path of writing for magazines. Let me also recommend Menaker’s memoir of his time in publishing, My Mistake. I believe this review extract from the Bookshop.org page is from someone you may be familiar with.

Taylor on what it means when he says he’s “revising” is also worth your time.

I would like to know who else can identify with “I Am a Dog. I Am About to Puke. Where Is the Good Rug” by Karen Scholl, via my good friends .

Recommendations

1. Since We Fell by Dennis Lehane

2. James by Percival Everett

3. So Far Gone by Jess Walters

4. Groundskeeping by Lee Cole

5. A Brave Man Seven Stories Tall by Will Chancelor

Chris C. - Denver, CO

I have read every single one of these books! This is my occasion to recommend one of my desert island choices, The End of Vandalism by Tom Drury.

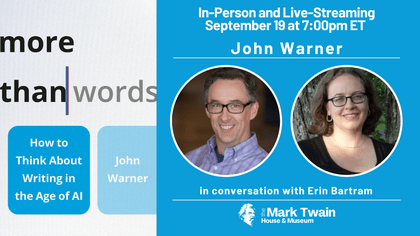

This is my last chance to plug my appearance at the Mark Twain House in Hartford on Sept. 19th at 7pm. I’ll be in conversation with Erin Bartram and the event will be both accessible in person at MTH and virtually online.

To reserve tickets for the in-person event you can go here.

To register for the live stream you can go here.

Registering ahead of time helps us know how many people to expect and for those joining virtually, you’ll get a handy calendar reminder. It’s going to be extremely entertaining and you don’t want to miss it.

Alrighty folks, the next few weeks get busy for ol’ John boy here with trips to speak and family obligations and other things, but I will do my best to put something up every weekend, but if you don’t hear from me, please forgive the absence.

In the meantime, stay connected to yourself and to others.

JW

The Biblioracle

I have had no issues walking away from online spaces when they ceased to deliver the benefits I received from them, starting with the Zoetrope All-Story writing portal, and including Facebook and Twitter. I’m assuming the same thing may be true someday of this platform. I think often about what allows me this perspective given that I have below average willpower and grit. In the end, it comes down to the fact that I think I’m indifferent to attention and value it only for its capacity to power the work I want to spend my time doing. When I voluntarily ceded editing the McSweeney’s website I had someone express amazement at giving up work that was so “important,” and which conveyed some amount of “power” in a particular sphere. I can honestly say neither of those things interested me. I just wanted to read and share funny stuff. When I wanted to do something else more I found someone who was better at the mission than I could ever be.