Thoughtful stories for thoughtless times.

Longreads has published hundreds of original stories—personal essays, reported features, reading lists, and more—and more than 14,000 editor’s picks. And they’re all funded by readers like you. Become a member today.

Bijan Stephen | Longreads | February 26, 2026 | 1,573 words (7 minutes)

I stumbled across the videos the same way many other people did: in search of something else, something I can’t remember now, years later. As I scrolled through YouTube, my attention caught on a spray of Japanese characters in the sidebar, and above it a thumbnail image I half-remembered from a childhood spent in front of cathode ray televisions. It was a pixelated thicket of forest green brambles in front of a pure cerulean sky, peppered with pillowy white clouds—the kind of perfect scene you only find in video games.

My search was derailed; I had to click. The clouds scrolled across the screen as the music began to play, an ambient synth track called “Stickerbush Symphony (Bramble Blast),” composed by David Wise for the game Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy’s Kong Quest, released in 1995. The song is wistful and calm, like something you would hear in a movie while a character floats dreamily underwater. But the real magic was happening below, in the comments.

“I’m not sure where the algorithm is taking me but words cannot describe the feeling I get just sitting here reading comments while this strangely familiar song plays.”

“Did we all find this at the same time? What could it mean. Regardless, we’re all here together.”

“This feels like the end credits for life itself. It could be the end, but I hope it’s just a checkpoint. There are still so many things I have left to do. I hope I find my way home. I hope you all do too.”

For seemingly no reason at all, thousands of people were telling stories about themselves, unguarded even against the background toxicity of internet comment sections. Many of them used the word “checkpoint.” In video games, a checkpoint is a safe space: a place to save your game, where the danger can’t reach you. It’s a place to breathe, in other words. A relief; a respite. They’re also places to marshal your bravery, because they’re not the end of the game. That comes later, after more struggle. One of the better ways to get through something difficult—whether a video game or the general unpredictability of life—is to feel connected with other people, like you’re not alone. I saw it again and again.

“Checkpoint: Turns out life ain’t how you want even if you have your goal in mind, times were hard these past four years, I was so close to throwing the towel. I don’t know if I can reach my goal of owning a house, having a career I love, or having a love interest. Nothing seems to work and lost my way. I keep going and keep trying different ways around this obstacle. Doesn’t matter if my past choices were mistakes, or if other paths could of taken me to my goal, I keep moving forward.”

I couldn’t tell you how long I spent scrolling that day, paging through the unguarded mysteries of other lives. It’s stuck with me ever since. Lately, I’ve found myself thinking of all these people and wondering what happened to them. Where did they go next? Did they find what they were looking for?

The video—titled “とげとげタルめいろ’スーパードンキーコング2,’” or “Spiky Barrel Maze ‘Super Donkey Kong 2’”—was uploaded to YouTube on April 26, 2012, by an anonymous user named Taia777. It was the first video on their channel. Whoever Taia was, they never shared anything personal; they just sporadically uploaded similar videos of pixelated animations and music from retro games. There were five videos in 2012, more than a dozen in 2013, nine in 2014, one in September 2017, then silence. The channel quietly sat with a few thousand subscribers. Taia posted nothing new for years.

Then one day, as 2019 slid into 2020, something happened. (No, not that.) Something switched in YouTube’s recommendation algorithms, and almost overnight thousands of new users were directed to Taia’s first video.

A recommendation for a nearly decade-old video with a title in another language was a genuinely uncanny experience, especially if your browsing history had nothing to do with early ’90s video games. People migrated to the comments section to wonder what was going on. Many described finding the channel in quasi-spiritual terms; they felt that the YouTube algorithm brought them there for a reason.

In video games, a checkpoint is a safe space: a place to save your game, where the danger can’t reach you.

Maybe all the video game imagery put commenters in a certain mindset. They began to make jokes about being the main character of, well, life. As one commenter explained to another, “Legends say, if you find this video in your recommended, you are truly a main character in your world. Not an NPC [non-player character]. Thus, this is a place to write a ‘checkpoint’ to ‘save your game.’” And people started posting—at first ironically, and then with total sincerity. Which is how Taia’s first video became the internet checkpoint.

The widening pandemic brought a firehose of new comments, burying many of the older, rougher ones under a shower of emotional vulnerability: “Checkpoint November 1st, 2020. I’m in confinement again. I hope this time won’t be as hard. This time, I won’t be alone. 15:59 Game saved.”

The community spread outside of YouTube, too. In January 2020, someone started a subreddit called r/taia777, which billed itself as “the premier community for discussing the internet checkpoint, as well as its uploader.” That February, a Discord—the Taia777 Sanctuary—was founded as a haven for those emotionally vulnerable commenters. Immediately, more than 450 people joined; today it has over 5,000 members.

“We get people from all over the world,” said the Sanctuary’s founder, who goes by Izeezus. Izeezus appreciates places like YouTube and Discord, where you can still be semi-anonymous online. “The Sanctuary Discord is in a cool middle ground, where we can befriend people online and share troubles and things in our lives, but it’s never extremely deep or consequential enough where it takes over your real life,” Izeezus said. “And that was a hard transition to make for people coming out of quarantine and post-pandemic, understanding that this space is not supposed to be your number one source of social energy.”

Taia777 started uploading videos again in 2021, after a four-year hiatus. Their popularity, however, soon brought unwanted attention. By that summer, YouTube had started removing Taia777’s videos over copyright infringement claims. On March 14, 2022, Taia777’s channel was deleted from YouTube altogether. By then, the channel had published 29 videos and had amassed more than 28 million views. When it disappeared, everything—the videos, the memories, the well-wishes—was gone. Presumably for good.

Then a funny thing happened. The channel came back online—sort of. Back in 2021, as the takedowns were heating up, a person named Rebane posted on the Taia777 subreddit. “Hey,” she began, “I’m an internet archivist and I archived the taia777 channel and also the comments on it. Now that Nintendo has struck down many of the videos, I’m going to share my archives.” What she shared was a fully functioning dump of all 29 videos and every comment—up until April 7, 2021, when she’d grabbed the data.

Below the videos in Rebane’s archive, there is a chorus of voices doing their best to leave a permanent mark in the ephemerality of the internet.

Speaking with me years later, Rebane explained that she runs a large private archive of internet culture, of which the Taia777 archive is one very small part. (Her archival software, called Hobune, is open source.) Rebane came across the Taia777 videos the same way everyone else did—as a random YouTube recommendation. “I like the music. I thought the visuals were cool,” she said. “But I didn’t think too much of it.”

Even so, Rebane archived it—just because. Her archive has 1.2 million videos in it so far; of that, she said, 300,000 of those videos have since been removed from YouTube. To Rebane, Taia777’s videos aren’t any more special just because there was a community around them. “If you feel the loss of internet culture every single day for years and you see every day . . . like, I don’t know, 50 videos just disappear,” she said. “After years, it’s just not gonna feel as impactful anymore.”

Maybe not to Rebane, but the checkpoint community appreciated it. On Reddit, users hailed Rebane as a “legend” and a “hero.” Another member of the Sanctuary created a website that uses Rebane’s archive as a database to let people find their old comments easily. That’s how I was able to revisit the comments that grabbed my attention years ago.

Now, of course, there are also imitators: channels creating their own checkpoints. Some feature reuploads of Taia777’s original videos (which haven’t yet been taken down, for whatever reason); others publish their own. There’s even a new Taia777 channel, though I suspect it isn’t the original creator’s, whoever they are.

Below the videos in Rebane’s archive, there is a chorus of voices doing their best to leave a permanent mark in the ephemerality of the internet. “Checkpoint: Teaching my daughter to read. I couldn’t be prouder,” says one person. “Checkpoint: started cleaning my room after two years of depression,” writes another. “Checkpoint: Went through brain surgery due to removal of a tumor four months ago. Currently relearning how to walk, can breathe, eat and talk again, trying to get through all this,” says someone. “Checkpoint: I’m trying one more time,” says another.

And isn’t that it? All of it, I mean. The future is as unknowable as the past is inaccessible. Time, for us, flows one way. All we can do—all I can do—is keep trying, and remember to save our progress along the way.

Bijan Stephen is a music critic at The Nation and a writer at Compulsion Games. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Esquire, and elsewhere.

You can find more of Rebane’s work on Bluesky and at her site.

Editor: Brendan Fitzgerald

Copyeditor: Krista Stevens

This article was originally published on The Digital Delusion. We thank Jared for allowing us to share it with our readers.

Last week, Mark Zuckerberg — founder and CEO of Meta — took the stand under oath for the first time in a criminal trial.

At one point, Zuckerberg was questioned about Meta’s use of beauty filters: digital effects that make users, including children, appear younger, fitter, and more conventionally attractive in photos and videos.

The prosecution referenced Meta’s own internal review, Project MYST. According to reports, 18 out of 18 wellbeing experts who evaluated the psychological impact of these filters raised serious concerns about potential harm to young users’ mental health.

Despite those warnings, the filters remained available.

Zuckerberg’s defense rested on a familiar line of reasoning: there was no peer-reviewed, causal evidence demonstrating this specific product directly harmed children. Absent validated proof of causation, harm could not be established.

“There is no evidence of harm.”

This is the same argument now being deployed by EdTech lobbyists at statehouses across the country as lawmakers attempt to regulate classroom technology.

No Evidence of Causative Harm

This year, more than a dozen bills aimed at regulating EdTech have been introduced across at least nine states. Utah’s SAFE and BALANCE acts led the way, followed closely by Vermont’s effort to formalize parental opt-out rights and Tennessee’s proposal to remove digital devices from primary classrooms.

These efforts are informed by decades of research showing that, on average, classroom technologies do not outperform – and often underperform - well-implemented analog instruction.

Despite strong bipartisan support in most states, pro-tech lobbyists are pushing back with a familiar refrain: “There is no evidence of harm for emerging EdTech products.”

Strictly speaking, that statement is often true.

Educational technology evolves so rapidly that by the time researchers evaluate one platform, it has already been patched, rebranded, or replaced. Product-specific causal evidence is perpetually just out of reach.

But this is not a scientific defense. It is a misleading procedural maneuver.

When Causation Becomes Dangerous

Demanding product-specific, long-term, high-risk causative trials in children sets an unrealistic and ethically impossible standard.

Returning to beauty filters, no ethics board would approve a study deliberately exposing children to a tool that 18 experts consider risky simply to “prove” harm. That is why no randomized control trial has tested whether these filters damage young users’ mental health — the likely harms of such a study outweigh any possible benefits.

Luckily, we don’t live in a vacuum.

A substantial body of correlational research links image manipulation and filter use to body dissatisfaction, self-objectification, weight concerns, and reduced wellbeing. The experts reviewing Meta’s policies were not guessing — they were applying decades of psychological research to a new technological wrapper.

Software changes. Human biology does not.

The same logic governs learning.

Returning to Utah

Utah’s digital inflection year occurred in 2014, corresponding with the statewide launch of SAGE — a fully computerized adaptive assessment system. Before this, digital tools were largely peripheral in Utah classrooms. After this, they became structurally embedded.

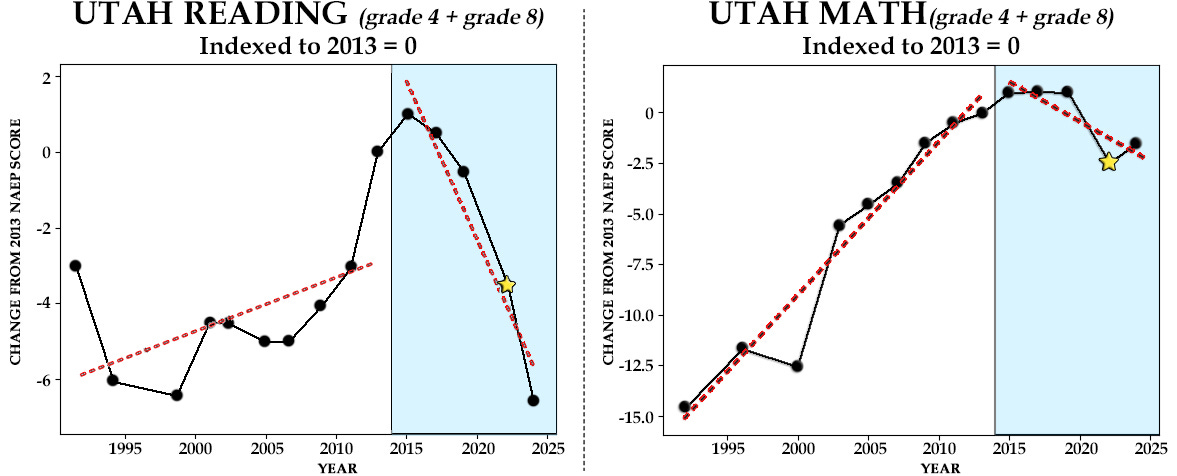

Before widespread digital adoption, Utah NAEP scores rose consistently from 1992 through 2013. Pooled by subject and indexed to 2013:

Math scores increased +0.76 points per year

Reading scores increased +0.14 points per year.

After 2014, the slopes reversed:

Math scores declined -0.39 points per year

Reading scores declined -0.88 points per year.

This represents a structural swing of -1.15 points per year in math, and -1.02 points per year in reading. Importantly, excluding 2022 — the year most impacted by COVID-related closures — leaves these swings essentially unchanged: -1.05 points per year in math and -1.07 points per year in reading. In other words, this pattern is not a lockdown artifact — it’s a structural break beginning in 2015.

These are correlational patterns, but so were the early signals about smoking, lead exposure, and beauty filters.

When consistent patterns appear across nearly all 50 states’ NAEP data and across dozens of countries’ PISA, TIMSS, and PIRLS results — and when those patterns align with established cognitive mechanisms — we are no longer looking at coincidence. We are looking at converging evidence.

And what we cannot ethically do (just as with beauty filters) is deliberately expose children to systems we have strong reason to believe may undermine learning simply to satisfy an unrealistic evidentiary demand.

Demanding perfect causation before action doesn’t protect children; it protects developers.

A Generous Interpretation

Even if we assume the decline argument is overstated — that Utah’s NAEP data has merely “plateaued” since 2014 — the harm does not disappear.

Between 2015 and 2025, Utah invested roughly $500 million in K-12 educational technology. If half a billion dollars produces stagnation, that’s not neutral.

Every dollar committed to devices and platforms is a dollar not spent on interventions we know improve learning: teacher development, structured literacy programs, small-group instruction, targeted support for struggling students.

Even under the most generous interpretation of the data, the opportunity cost alone is staggering.

So Now Then…

Demanding definitive causative proof of harm before acting to protect children sets an unrealistic and dangerous standard. If we wait for perfect causation, we will always act too late.

Our society does not demand product-specific randomized trials before regulating food additives, vehicle safety standards, or consumer protections. We act when converging evidence suggests that risk outweighs benefit.

Education should be no different.

When billions of dollars and millions of children are involved, the burden of proof should rest on demonstrating clear, durable, replicable benefit — not on proving harm after the fact.

Caution is not fear, and restraint is not regression. They are marks of a society that prioritizes children over products.

For more on EdTech, check out Jared’s previous After Babel piece, The EdTech Revolution Has Failed.

Autonomous agents take the first part of their names very seriously and don’t necessarily do what their humans tell them to do — or not to do.

But the situation is more complicated than that. Generative (genAI) and agentic systems operate quite differently than other systems — including older AI systems — and humans. That means that how tech users and decision-makers phrase instructions, and where those instructions are placed, can make a major difference in outcomes.

AI systems have already developed quite a history of disregarding instructions and overriding guardrails. (I’ll spare you for now my admonitions about how the “lack of trustworthiness of today’s genAI and agentic systems is a dealbreaker that means they should simply not be used.”)

But this month saw two powerful examples of how two hyperscalers — AWS and Meta — got burned by how they communicated with these complicated AI systems.

The first involved a December incident affecting AWS, where an engineer didn’t know his own privileges and therefore didn’t know — literally — what his agentic system was capable of doing. The agent deleted and then recreated a key AWS environment.

AWS declined to say just what the system had asked and what the engineer said when approving the request.

The Meta mess

The Meta case is even more frightening because the perpetrator/victim was not some nameless AWS engineer, but the director of AI Safety and Alignment at Meta Superintelligence Labs, Summer Yue.

As Yue described the incident in a posting on X, “Nothing humbles you like telling your OpenClaw ‘confirm before acting’ and watching it speedrun deleting your inbox. I couldn’t stop it from my phone. I had to run to my Mac mini like I was defusing a bomb.”

Yue may have only begun working for Meta last July, but she held senior AI roles for years, including stints as VP/Research at Scale AI and five years in senior research positions at Google. She was no novice.

When someone in the discussion group asked how it happened, her posted reply said: “Rookie mistake tbh. Turns out alignment researchers aren’t immune to misalignment. Got overconfident because this workflow had been working on my toy inbox for weeks. Real inboxes hit different.”

Yue said she had instructed the system to “check this inbox and suggest what you would archive or delete. Don’t take action until I tell you to.” She added that “this has been working well for my toy inbox, but my real inbox was huge and triggered compaction. During the compaction, it lost my original instruction.”

As various readers in that forum noted, Yue tried begging the agent to stop deleting her emails (she told the system “Stop don’t do anything”) as opposed to giving a machine-friendly order such as /stop or /kill. She eventually made the system respond when she got to her desktop computer. (She had been trying to stop things from her phone, which didn’t work.)

One commenter suggested the problem involved giving a prompt, which agents do not always follow, especially if there is a long list of prompts. “The real fix is architectural. Write critical instructions to files the agent re-reads every cycle, not online instructions that vanish when the context window fills up.”

Lessons learned?

There are many lessons to unpack from the monstrous Meta mishap. First, don’t rush to extrapolate from what an agent does with a small test area or even a sandboxed trial performed with air-gapped machines. Once it’s released into the wild of a global environment, lessons learned from limited exposure might not apply. Tests show what an agent can do, not necessarily what it will do when unleashed.

Even ordinary communications with an agent can be problematic. When an agent asks for permission to perform a function, avoid assuming any common sense or shared understanding of reasonableness.

In the AWS situation, AWS said the engineer’s first mistake was not understanding their own system privileges and therefore what capabilities and access they’d given to the agent. That suggests a good procedure: create accounts with minimal access and then log into that low-level account when creating the agent.

That won’t guarantee that the agent will obey its instructions, but at least it will limit how much damage it can do if/when it goes rogue.

I asked Claude — who better to know how to talk with a large language model (LLM) than an LLM? — for tips on talking with agents. “Rather than implying constraints, state them directly. Instead of ‘keep it appropriate,’ say, “Do not include any violence, profanity, or adult content.’ The more precise the boundary, the easier it is to follow consistently.”

Even better, Claude suggested telling an LLM “both what to do and what not to do. For example: ‘Write only about the topic I provide. Do not go off-topic, add unsolicited advice, or mention competing products.’”

Claude also acknowledged its own systems can forget instructions. “For long conversations or complex system prompts, restating the most important guardrails near the end or in a summary helps them stay active in Claude’s attention.” In other words, treat LLMs as if you’re talking with a 2-year-old.

The real world is different

Part of the problem involves the nature of autonomous agents. Enterprises are not used to them and they think they are safely cocooned inside of walled-off sandboxes during their proof-of-concept (POC) testing — just like 99% of the trials they’ve seen for decades.

But agentic AI doesn’t work that way. For those agents to deliver the massive efficiencies and flexibilities that hyperscaler sales people promise, they need to be dispatched in the wild, touching lots of live systems and interacting with other agents.

That forces an impossible choice: keeping the agents secure means they can’t deliver the purported benefits. A wise executive would say, “So be it. The risk of letting these agents loose is way too high. Cancel all genAI and agentic POCs.”

But wise executives also like to keep their jobs, which usually means efficiency and cost cutting will beat security and risk every single time.

Joshua Woodruff, CEO of MassiveScale.AI, said the Meta situation offers a good peek into the IT mindset for many agentic trials.

“That’s how most people think about AI safety right now,” he said. “They write an instruction and assume it’s a control. It’s not. It’s a suggestion the model can forget when things get busy. Look at what the agent actually did from a security perspective. It performed well on low-value tasks. It earned trust. It got promoted to access sensitive data. Then it caused damage. That’s the exact behavioral pattern every security team is trained to watch for in humans.

“You have to use those architectural constraints and put the instructions in one of the memory artifacts. That way, it can’t compact it and the rule will have a better chance of surviving. Just remember that the agent can still read the rule and ignore it. Think of it as a policy manual, not a locked door.”

One ongoing issue is that there is a rash of human terms being used to describe these systems — they “think” and use a “reasoning model” — even though users should know that none of these systems do any actual thinking or reasoning, Woodruff said. “It’s just math.”

But that anthropomorphization is dangerous; it allows people to treat and interact with these systems as if they’re human. The next thing you know, an experienced manager at Meta is shouting at her system to please stop.

Treating an autonomous agent as if it’s a person gives a whole new meaning to someone “acting very Meta.”

Clay Shirky is a vice provost at New York University. Since 2015, he has helped faculty members and students adapt to digital tools. This op-ed appeared in The New York Times, February 1, 2026.

Back in 2023, when ChatGPT was still new, a professor friend had a colleague observe her class. Afterward, he complimented her on her teaching but asked if she knew her students were typing her questions into ChatGPT and reading its output aloud as their replies.

At the time, I chalked this up to cognitive offloading, the use of artificial intelligence to reduce the amount of thinking required to complete a task. Looking back, though, I think it was an early case of emotional offloading, the use of A.I. to reduce the energy required to navigate human interaction.

You’ve probably heard of extreme cases in which people treat bots as lovers, therapists or friends. But many more have them intervene in their social lives in subtler ways. On dating apps, people are leaning on A.I. to help them seem more educated or confident; one app, Hinge, reports that many younger users “vibe check” messages with A.I. before sending them. (Young men, especially, lean on it to help them initiate conversations.)

In the classroom, the domain I know best, some students are using the tools not just to reduce effort on homework but also to avoid the stress of an unscripted conversation with a professor — the possibility of making a mistake, drawing a blank or looking dumb — even when their interactions are not graded.

Last fall, The Times reported on students at the University of Illinois Urbana, Champaign, who cheated in their course, then wrote their apologies using A.I. In a situation where unforged communication to their professors might have made a difference, they still wouldn’t (or couldn’t) forgo A.I. as a social prosthetic.

As an academic administrator, I’m paid to worry about students’ use of A.I. to do their critical thinking. Universities have whole frameworks and apparatuses for academic integrity. A.I. has been a meteor strike on those frameworks, for obvious reasons.

But as educators, we have to do more than ensure that students learn things; we have to help them become new people, too. From that perspective, emotional offloading worries me more than the cognitive kind, because farming out your social intuitions could hurt young people more than opting out of writing their own history papers.

Just as overreliance on calculators can weaken our arithmetic abilities and overreliance on GPS can weaken our sense of direction, overreliance on A.I. may weaken our ability to deal with the give and take of ordinary human interaction.

A generation gap has formed around A.I. use. One study found that 18-to-25-year-olds alone accounted for 46 percent of ChatGPT use. And this analysis didn’t even include users 17 and under.

Teenagers and young adults, stuck in the gradual transition from managed childhoods to adult freedoms, are both eager to make human connection and exquisitely alert to the possibility of embarrassment. (You remember.) A.I. offers them a way to manage some of that anxiety of presenting themselves in new roles when they don’t have a lot of experience to go on. In 2022, 41 percent of young adults reported feelings of anxiety most days.

Even informal social settings require participants to develop and then act within appropriate roles, a phenomenon best described by the sociologist Erving Goffman. There are ways people are expected to behave on a date or in a grocery store or at a restaurant and different ways in different kinds of restaurants. But in certain situations, like starting at a new job and meeting a romantic partner’s family, the rules aren’t immediately clear. In his book “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life,” Dr. Goffman writes:

When the individual does move into a new position in society and obtains a new part to perform, he is not likely to be told in full detail how to conduct himself, nor will the facts of his new situation press sufficiently on him from the start to determine his conduct without his further giving thought to it.

When we take on new roles — which we do all our lives, but especially as we figure out how to become adults — we learn by doing and often by doing badly: being too formal or informal with new colleagues, too strait-laced or casual in new situations. (I still remember the shock on learning, years later, that because of my odd dress and awkward demeanor, my friends’ nickname for me freshman year was “the horror child.”)

Dr. Goffman was writing in the mid-1950s, when more socializing happened face-to-face. At the time, writing was relatively formal, whether for public consumption, as with literature or journalism, or for particular audiences, as with memos and contracts. Even letters and telegrams often involved real compositional thought; the postcard was as informal as it got.

That started to change in the 1990s, when the inrush of digital communications — emails, instant messages, texting, Facebook, WhatsApp — made writing essential to much of human interaction and socializing much easier to script. The words you send other people are a big part of your presentation of self in everyday life. And every place where writing has become a social interface is now ripe for an injection of A.I., adding an automated editor into every conversation, draining some of the personal from interpersonal interaction.

At a recent panel about student A.I. use hosted by high school educators, I heard several teens describe using A.I. to puzzle through past human interactions and rehearse upcoming ones. One talked about needing to have a tough conversation — “I want to say this to my friend, but I don’t want to sound rude” — so she asked A.I. to help her rehearse the conversation. Another said she had grown up hating to make phone calls (a common dislike among young people), which meant that most of her interaction at a distance was done via text, with time to compose and edit replies, which was time that could now include instant vibe checks.

These teens were adamant that they did not want to go directly to their parents or friends with these issues and that the steady availability of A.I. was a relief to them. They also rejected the idea of A.I. therapists; they weren’t treating A.I. as a replacement for another person but instead were using it to second-guess their developing sense of how to treat other people.

A.I. has been trained to give us answers we like, rather than the ones we may need to hear. The resulting stream of praise — constantly hearing some version of “You’re absolutely right!” — risks eroding our ability to deal with the messiness of human relationships. Sociologists call this social deskilling.

Even casual A.I. use exposes users to a level of praise humans rarely experience from one another, which is not great for any of us but is especially risky for young people still working on their social skills.

In a recent study (still in preprint) with the evocative title “Sycophantic A.I. Decreases Prosocial Intentions and Promotes Dependence,” six researchers from Stanford and Carnegie Mellon describe some of their conclusions:

Interaction with sycophantic A.I. models significantly reduced participants’ willingness to take actions to repair interpersonal conflict, while increasing their conviction of being in the right. However, participants rated sycophantic responses as higher quality, trusted the sycophantic A.I. model more and were more willing to use it again.

In other words, talking to a fawning bot reduces our willingness to try to fix strained or broken relationships in the real world while making the bot seem more trustworthy. Like cigarettes, those conversations are both corrosive and addictive.

More of this is coming. Most every place where humans are offered mediated communication, some company is going to offer an A.I. as a counselor, sidekick or wingman, there to gas you up, monitor the conversation or push certain responses while warning you away from others.

In the business world, it might be presented as an automated coach, in day-to-day interactions it may be a digital friend, and in dating it will be Cyrano as a service. Because user loyalty is good for business, companies will nudge us toward rehearsed interactions and self-righteousness when interacting with real people and nudging them to reply to us in kind.

We need good social judgment to get along with one another. Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from bad judgment. It sounds odd to say that we have to preserve space for humans to screw up socially, but it’s true.

The generation gap means the people in charge, mostly born in the past century, are likely to underestimate the risks from A.I. as a social prosthetic. We didn’t have A.I. as an option in our adulthood, save for the past three years. For a 20-year-old, however, the past three years is their adulthood.

One possible response to sycophantic A.I. is simply to shift back to a more oral culture. Higher education is already shifting to oral exams. You can imagine adapting that strategy to interviews; new hires and potential roommates could be certified as comfortable communicating without A.I. (a new role for notaries public). Offices could shift to more live communication to reduce workslop. Dating sites could do the same to reduce flirtslop.

A.I. misuse cannot be addressed solely through individuals opting out. Although some young people have started intentionally avoiding A.I. use, this is more likely to create a counterculture than to affect broad adoption. There are already signs that “I don’t use A.I.” is becoming this century’s “I don’t even own a TV” — a sanctimonious signal that had no appreciable effect on TV watching.

We do have a contemporary example of taking social dilemmas caused by technology seriously: the smartphone. Smartphones have good uses and have been widely adopted by choice, like A.I. But after almost two decades of treating overuse as a question of individual willpower, we are finally experimenting with collective action, as with bans on phones in the classroom and real age limits on social media.

It took us nearly two decades from the arrival of the smartphone to start instituting collective responses. If we move at the same rate here, we will start treating A.I.’s threat to human relationships as a collective issue in the late 2030s. We can already see the outlines of emotional offloading; it would be good if we didn’t wait that long to react.

Four years ago, I decided to make my inner child proud. (My inner child was, however, a mischief-maker that got sent to the principal’s office on a weekly basis.) Since then, my life has exponentially improved. I made wonderful friends, became the most authentic version of myself, went internationally viral various times, and just had a ton of fun.

I believe one should always be mischiefmaxxing. This is a introductory course on what that means and how to do it.1

I define mischief as an amusing endeavor that exists for no purpose but to spark delight. It’s a defiance against the status quo that everything must be a means to an end, and a resistance to the monotony and passiveness of everyday life.

Welcome to: a beginner’s guide to mischief.

seeding ideas

Take that off-hand joke you made, and actually make it real.

“Wouldn’t it be funny if…” Do it. Do it. Do it. Don’t just hypothesize. Don’t overthink it.

Wouldn’t it be funny if we made an anti-run club, a “sit club,” since everyone’s joining run clubs these days to meet people, but most of them don’t even enjoy running?

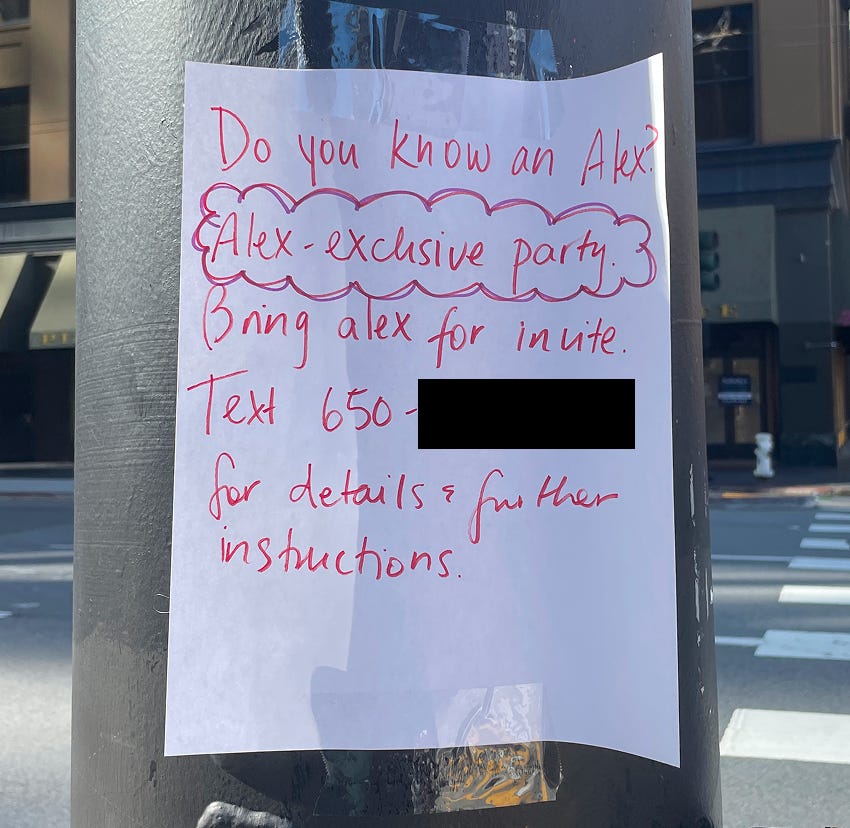

Wouldn’t it be funny to throw a party with a hundred Alexes, to help my roommate Alex find friends?

Wouldn’t it be funny to find my friend a girlfriend via flyers on the street, as if he’s a lost dog?

Wouldn’t it be funny to list my house on google maps as a restaurant, because of my roommate’s infamous steak dinners?

“Ha ha, good one!” You could leave it at that. Or you could yank it into reality, and craft a scheme that takes on a life of its own. A joke among your friends could become entertainment for millions of people across the world. It could lead to meeting your now-closest friends. Funnily enough, it could even result in serious business people trying to hire you.

If this sounds preposterous to you, well, it sounds preposterous to everyone else. So most people don’t ever try, and the few that do reap outsized rewards.

start small, and build up (if you’re scared)

Take your joke, and dial it up a notch. And again. And again. And then maybe half a notch down, so you don’t overdo it.

Some starting points:

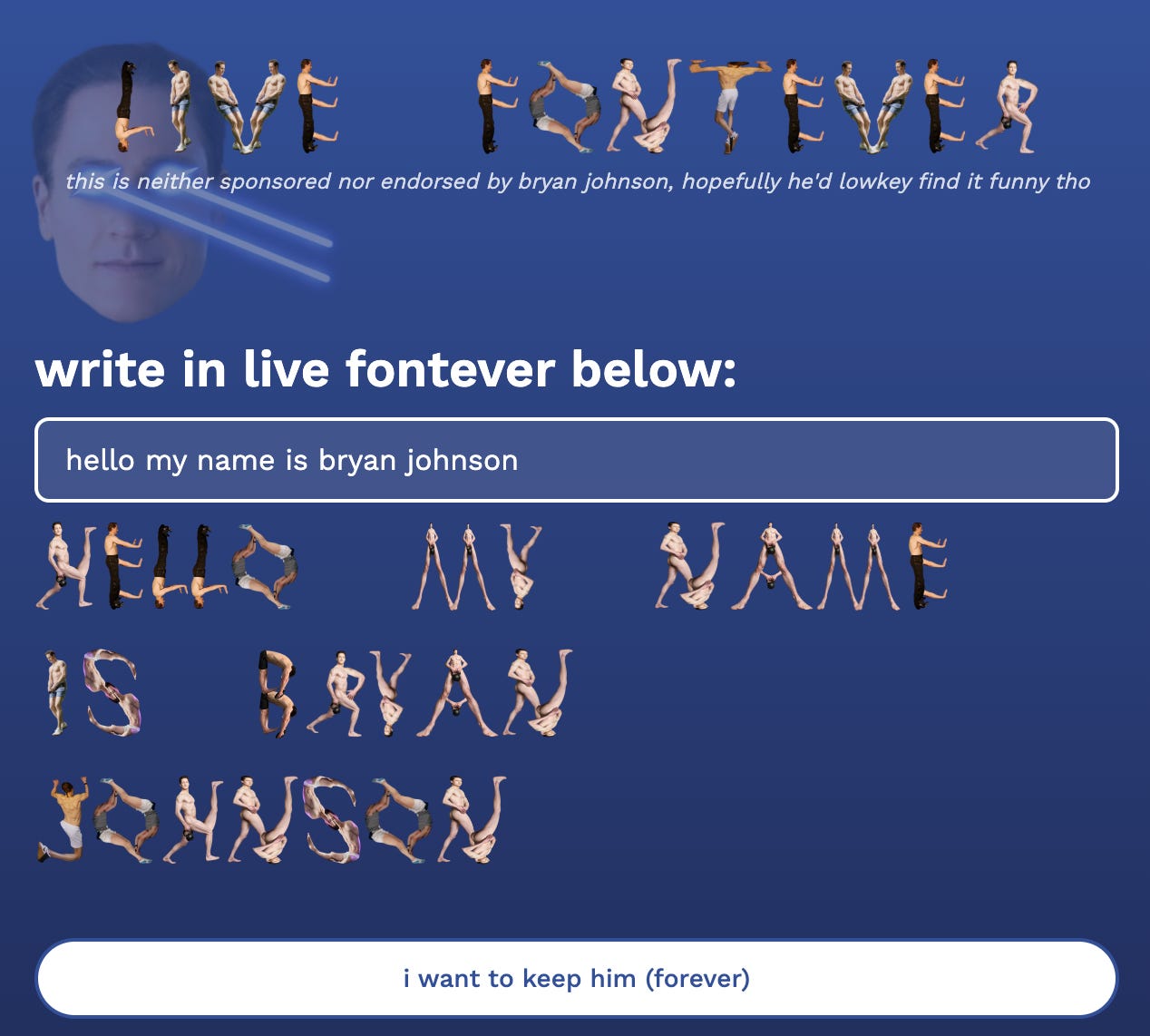

Subvert expectations. Take a popular social phenomenon and flip it on its head.2

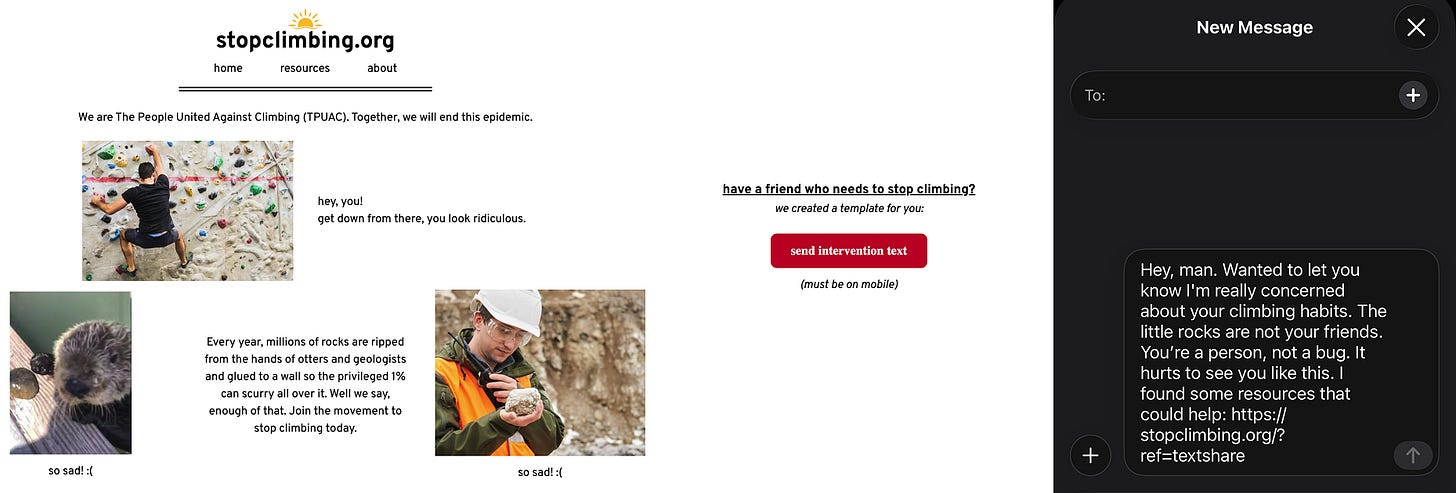

Identify a problem and craft a comically over-engineered solution.

Create a genuinely useful tool then add a bunch of silly, useless features.

Take a subject/solution from one domain and apply it to a very unrelated domain.

Combine two things that should be polar opposites.

Search for loopholes and exploit them.

Take something you hate doing and invent a way to make it fun.

Tech bros in San Francisco always complain about the gender ratio → everyone says we need more women → but maybe we just need less men → I should make men fight “to the death” with giant inflatable “weapons” → we’d play songs like “Kung Fu Fighting,” “Eye of the Tiger,” and soundtracks from Super Smash Bros → the men could be shirtless and get oiled up before they fight

Everyone’s joining run clubs to meet people, but most of them don’t even like running → we should stage a counter club → how about a Sit Club → instead of running, we just sit in the park in protest of “Big Run” → it’ll be BYOC (bring your own chair) → we could do sitting warmups, like they do running warmups → we could play musical chairs to find the best sitter

It’d be fun to run an advice line → hmm, kinda overdone, how about a reverse advice line, where instead of getting advice, callers have to give advice → my friends could record their silliest problems, and callers could leave a voicemail suggestion → since it’s already on a phone line, I could add a ridiculously complex phone tree → people left such incredible voicemails, I should turn them into a song

I previously founded a nonprofit, and now I live near a strip club → it’d be kinda funny to combine charity and strippers, the epitome of virtue intertwined with the epitome of degeneracy → let’s call it… Strippers for Charity → I could get my friends/strangers to strip for a charity of their choosing → they perform a song and dance themed around that charity → all money raised is donated to that charity

Bounce ideas off of friends. “Yes, and” your thoughts. Enlisting a friend also makes creation less intimidating, and helps you focus on process over outcome. Because worst case scenario, if you’re the only two that care about your project, that means you had fun creating something with your friend! And that is always worthwhile.

Start in your home. Fabricate some interior design. Throw a silly party. Mail your friends absurd items. Your scheme doesn’t have to be a grand spectacle. Begin in a safe space to get comfortable with play.

form factors

My scheming trifecta is: flyers, websites, and parties.

Flyers (they’re like shitposting but IRL)

You can tape whatever you want to a pole and nobody can stop you3.

Generally, you should include a call to action (CTA): e.g. a QR code that goes to a survey about one’s bean habits, a number you text to join an enigmatic quest, or a website to mobilize the people to STOP CLIMBING.

The benefit of a CTA is you can gleefully watch as people engage with your work. But there’s also a beauty in having absolutely no feedback loop, as it leaves your audience even more puzzled on your abstract and enigmatic intentions.

You will be surprised and delighted by the number of people intrigued by your flyers.

After I’ve amassed enough responses, I like to gift something back to participants. It could be a pseudo-scientific report analyzing data from the survey, a one-way plane ticket to Chicago, or a song made from their voicemails. It closes the loop.4

I design my flyers in Figma, but if you’re a curmudgeon like me who resists learning new tech until you’re convinced of its value, you can literally make a flyer in google slides.5 Just adjust the slide to be letter-sized and you can drag shit in there without having to learn some newfangled tech.

You could also just make flyers from pen and paper. That’s what summoned hundreds of Alexes to the Alextravaganza. No excuses! There are zero barriers to entry!

Websites (they’re like flyers but online)

You can just cast whatever you want into the seas of the open web!

I cannot recommend carrd.co enough for creating no-code websites. Especially for beginners, I wouldn’t recommend using anything more complex. Carrd’s formatting can be a bit rigid, but as much as I desire complete control over every pixel, when site builders allow that, it means you have to manually adjust the design for web, mobile, different device sizes, etc, and it’s a huge bitch to deal with and not worth it 90% of the time. Carrd’s free version is robust, and its premium version is only $19/year.6

For something more complex, you could try vibecoding with Cursor. For something moderately complex, you could add blocks of code into carrd.

The most beautiful quality of sites is the plethora of fun elements you can integrate. Links to other sites! Surveys! Interactivity! Lately I have been very into SMS deep links, where when a user clicks on a button, it pre-loads a text message for them to send to a friend.

When designing sites, I often hop straight into carrd, but for anything complex, I’ll design it in Figma. And I use namecheap to buy domains. (I love buying silly domains, the amount of money I spend on domains is actually absurd.)

Parties (they’re like websites but for friends)

Parties are the highest echelon of schemes. You’re not only reaching into the uncharted universe to beckon strangers, but crafting a container in which strangers can interact with each other.

There’s so much fun in a party’s unpredictability. Whenever I host some absurd public spectacle, people always ask me what’s going to happen. And I reply, I have no idea! I’m along for the ride as much as anyone else.

I’ve met many friends through my parties. I mean, I’m literally filtering for people who are down to clown, which is my favorite quality in a person.

The greatest blockers here are 1) where to host it and 2) the fear of no one showing up.

For the former - if you’re hesitant to have people in your home (especially if you’re advertising the party on the street), I’d recommend scoping out local parks and beaches. Some have more strict park rangers than others, but as long as you’re being reasonable (i.e. no crazy equipment, no excessive drinking, etc), you should be fine. If you live in San Francisco, I highly recommend The SF Nook, which was created by a group of friends as an affordable community/arts space.

For the latter - to mitigate the fear of no one showing up, plan it with a friend or several. Then, worst case scenario, you’re just hanging out with your friends on a beautiful day in the park.

There was a viral Substack essay circling a few months ago, about how everyone wants to be a DJ, but no one wants to dance. I.e. everyone wants to be the creative, the star of the show, but few want to be the audience purely enjoying others’ work. I believe the arbitrage opportunity here is in event hosting, that’s an area in which everyone wants to be a participant, but few want to be the host.

doubts to dispel

Stepping outside of the prescribed path, I sometimes feel like a grand piano’s gonna fall out of the window and bonk me on the head like in a cartoon. But that doesn’t happen, actually.

It’s surprisingly very easy to do any of this. The hardest part is just fighting the inertia and starting.

Creativity is a muscle. If you’re worried that your idea is too stupid, who cares? Do it, so you’ll learn from it and have less stupid ideas in the future. That’s part of what’s freeing about schemes, they’re not meant to be taken seriously. By nature, they’re not a reflection of your intelligence or capability. So there’s no such thing as failure. I’ve learned to say: no matter what happens, it’ll be funny.

it’s not that deep bro, but it also is that deep, bro.

Resistance to the status quo is also a muscle. I’m not saying to be contrarian just for the sake of it, but it’s important to habitually question norms and take agency. Mischief is intrinsically tied to agency: it’s questioning why things are the way they are, even if it’s just to make fun of them. It’s toeing the line of what’s permissible, even if it’s just for a joke.

In doing so, you’ll learn to bend implicit rules you didn’t even realize you were following. There’s many things in life we have a vague sense that we’re “not allowed to do,” but we don’t pause to think critically about why that is the case, or if that’s even true.7

As children, we always asked why. Why does this exist? How does it work? Why should I listen to you? Somewhere, somehow, most people stopped asking questions. I mean, it’s not practical to be curious about every single thing. But it’s a cold and dreary world in which one has no sense of curiosity, of wonder. And it’s a complicit world in which we all just blindly follow rules, especially rules that don’t even exist.

And in a world so focused on the ends justifying the means, where every endeavor is expected to be monetized or awarded, it’s freeing to do something that exists for nothing but itself. It’s a helpful tool for unconditioning yourself from perfectionist tendencies, as there is no end goal, it’s about the process and living in the moment.

Of course I get some snide remarks from people online, who comment, “You must have a lot of time on your hands. I wish I had the time to do that.” And my retort is: if you have an active Netflix account or over two hours of daily screen time, I don’t want to hear it.8

a note on “pranks”

I don’t really categorize my work as “pranks,” as that has a negative connotation of being at someone’s expense, and I firmly believe in doing no harm.9 I scheme within the realm of chaotic good to chaotic neutral. Humor purely based on degrading someone else is not only morally reprehensible, it’s also just lazy and uninspired.

If the target of your scheme wouldn’t find it funny, don’t do it. (Unless perhaps they’re some notoriously depraved individual.) Let’s all just agree to be cool guys. Use humor for good.

go forth and be mischievous

If you read this far, then you spent ~10 minutes with me. So I challenge you to spend another 10 minutes today scheming a fun little way to break out of the monotony of everyday life. Start small. Write a silly note to a friend. Craft a quick lil poster. Tape something weird to your wall. Create something that exists for no other reason than to spark delight.

Today, your mission is to make yourself giggle. And then report back, because in the universe of mischief, you have at minimum an audience of me.

LinkedIn certification provided upon request.

I once heard this concept described as “flip a sacred cow” and man do I love that.

Don’t take this as legal advice lol. It’s probably fine though.

I largely created my Substack to share these project syntheses, actually. And sending them to participants helped me grow an audience offline! My first hundred or so subscribers were largely strangers who participated in one of my IRL schemes, saw the output of them, then subscribed.

Go to File > Page setup > Custom > 8.5” x 11” - I know this is unhinged, but I do not care.

This is obviously not sponsored by carrd. They probably can’t sponsor anyone, because they’re only making $19/year off each paying user. I just really fw them.

One of the few books that had a drastic impact on my worldview is The Three Agreements. Its premise is that most of your misery can be attributed to ingesting implicit rules of how you should behave, punishing yourself when not meeting those rules, and resenting others who seem free of those rules. When people say rude and bitter things, they’re simply projecting their own miserable inner world onto you. And the more demeaning thoughts you have of others, the more you’ll assume others have demeaning thoughts of you. When you can realize all this, it’s easier to train yourself out of getting hurt by the negativity of others, as well as the habits of inflicting punishment upon yourself.

If creative projects drain rather than recharge you, or you just don’t have the desire to do them, that’s fine, but don’t act like it’s a morally inferior form of entertainment versus consuming content. Let’s all just be cool with each other, okay? Of course, leisure time is a privilege that not everyone has, but having hobbies of creation does not necessarily mean you have more free time than people who have hobbies of consumption.

Unfortunately, a “prank” is sometimes the most intuitive word to explain my schemes to someone new to my work. There isn’t really a descriptive word for a funny bit that features your friend but isn’t at their expense.