I'm sitting here with my fingers hovering over the keyboard, wondering if I have any business writing about imposter syndrome when I'm experiencing it in real-time. The irony isn't lost on me—here I am, about to explore the very phenomenon that's making me question whether I'm qualified to explore it at all. But maybe that's exactly the point. Maybe the best way to understand something is to be drowning in it while you're trying to map its depths.

The term "imposter syndrome" was coined in 1978 by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes to describe high-achieving individuals who couldn't internalize their success—originally observed in women, though we now know it spans all genders. They called it "imposter phenomenon" then, documenting how accomplished people attributed their achievements to luck, timing, or deception rather than competence. What strikes me about their original research is how they documented something that felt deeply personal to so many people, yet had remained largely unnamed and unexamined. Modern research suggests this feeling is far from rare. Studies consistently find that ~ 70% of people experience imposter syndrome at some point in their lives, making it less an aberration than a nearly universal human experience.

But I've been thinking about this differently lately, especially as I've been wrestling with my own creative paralysis. There's this mantra I've adopted over the years: "just ship." It sounds almost brutally simple. Just get your work out there. Just let it exist in the world. Just press publish, submit the proposal, send the email, show up.

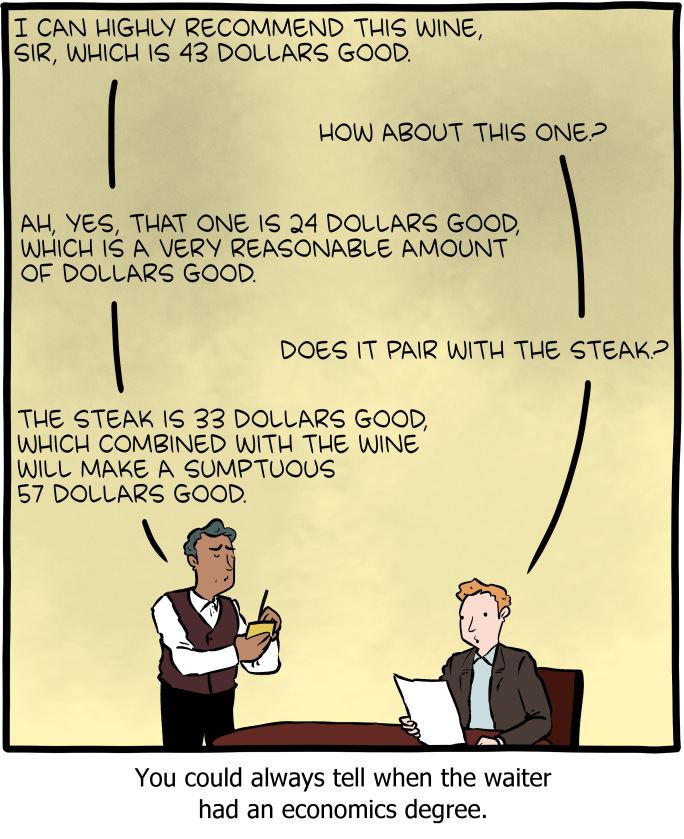

The phrase has Silicon Valley DNA, and its evolution tells a story. Steve Jobs lit the fuse in 1983 with "real artists ship"—a mantra he wielded to push the Macintosh into existence, according to engineer Andy Hertzfeld's memoir. Later, 37signals turned it into "just ship it!" in their widely-read Getting Real ebook, spreading it through early Ruby-on-Rails circles in the mid-2000s. Seth Godin's books (Linchpin, The Practice) and blog posts then mainstreamed "just ship" as broader creative gospel, while startup culture blasted it into meme-hood with Facebook's "done is better than perfect" and countless TechCrunch pieces echoing the ship-early ethos.

But the more I sit with this idea, the more I realize it's not about productivity or hustle culture or any of that relentless optimization thinking that's colonized our relationship with creativity.

It's about contact with reality.

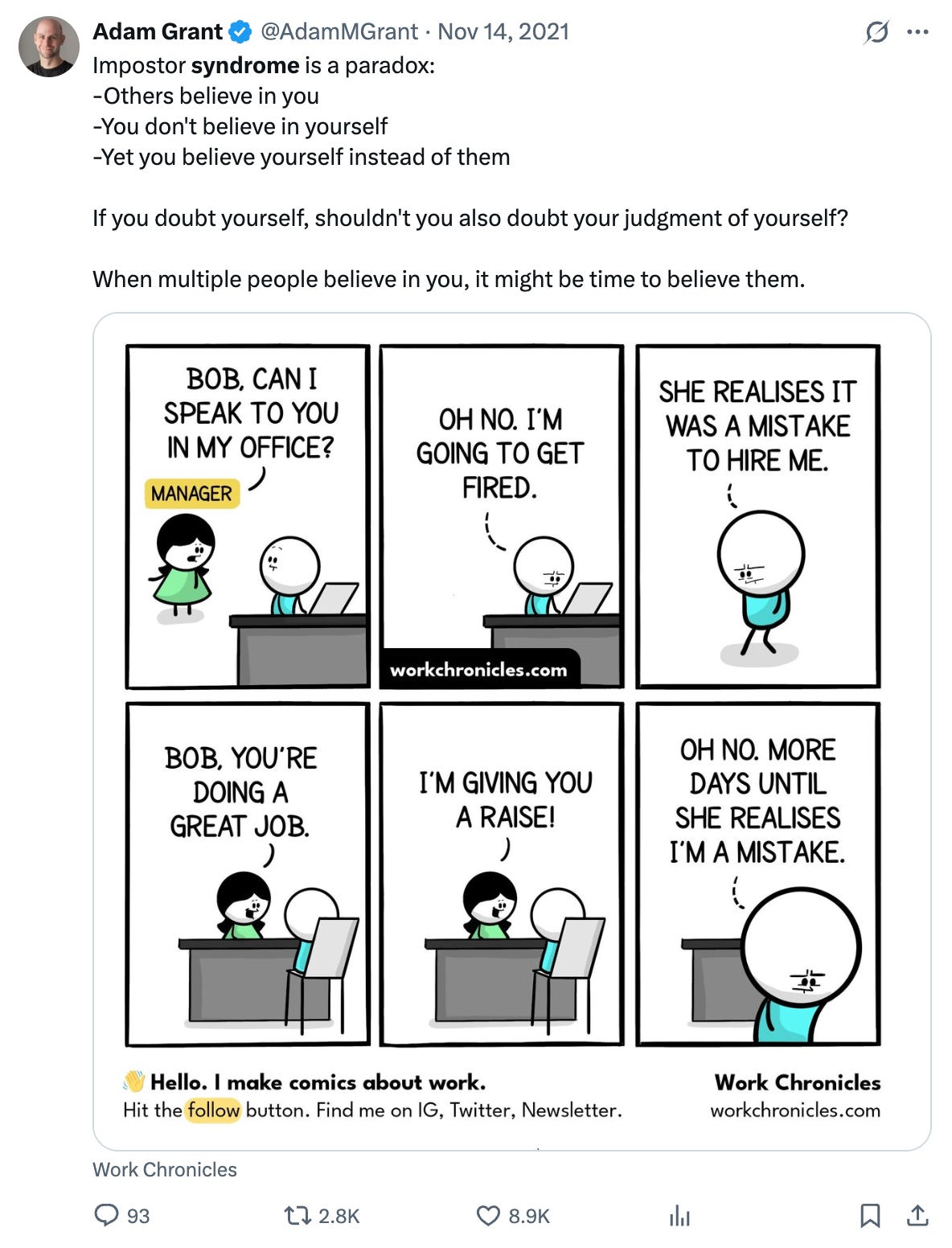

See, I think imposter syndrome thrives in the space between our private worlds and the public sphere. It feeds on the gap between what we think we know and what we're willing to test against the world. It's the voice that says, "You're not ready," or "Someone else has already said this better," or my personal favorite, "Who are you to think this matters?" These aren't just thoughts—they're protective mechanisms, evolved responses to the very real social risks of being seen, judged, and potentially rejected.

The thing is, our brains are ancient machines trying to navigate a modern world. When I feel that familiar tightness in my chest before sharing something I've written, I'm experiencing the same neural pathways that kept my ancestors alive by maintaining their standing in small tribal groups. Being cast out meant death. Being wrong meant losing status, which meant losing access to resources, mates, safety. The stakes felt existential because they were.

But here's what I've started to understand about the "just ship" philosophy: it's not about ignoring these fears or powering through them with toxic positivity. It's about recognizing that our ideas—and by extension, ourselves—can only grow through contact with reality. They need friction. They need to bump up against other minds, other experiences, other ways of seeing. They need to be tested, challenged, refined, or sometimes discarded entirely.

I think about the writers I admire most, and they all seem to share this quality of being willing to be wrong in public. Joan Didion didn't wait until she had everything figured out before she started writing about what it meant to be a woman in America. James Baldwin didn't wait for perfect prose before he began exploring the complexities of race and sexuality and belonging. They shipped their uncertainty, their questions, their half-formed thoughts, and in doing so, they gave us permission to do the same.

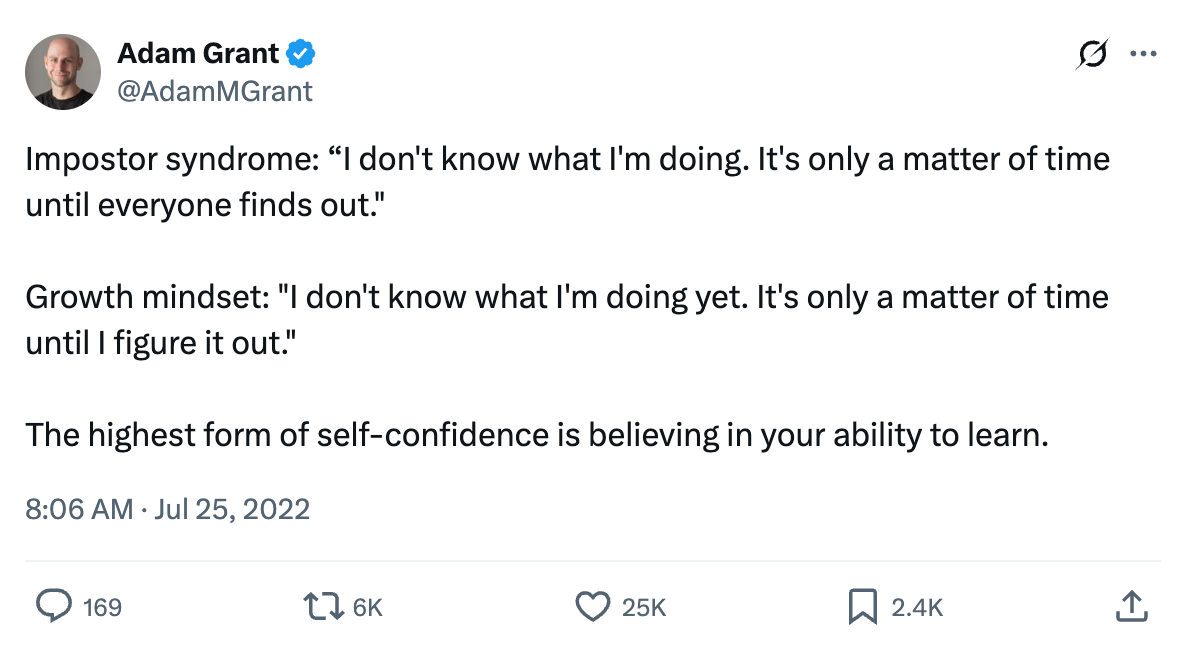

The imposter syndrome whispers: "You don't know enough yet." But knowing enough is a moving target. There's always another book to read, another expert to consult, another angle to consider. At some point, the pursuit of readiness becomes a sophisticated form of procrastination. We convince ourselves we're being responsible, thorough, professional, when really we're just scared.

I've been thinking about this in the context of creative work especially. There's something uniquely vulnerable about putting your thoughts, your voice, your particular way of seeing into the world. It's not like shipping a product where success can be measured in clear metrics. When you ship an idea, you're shipping a piece of yourself. And if people don't resonate with it, if they ignore it or criticize it or misunderstand it, it can feel like they're rejecting you.

But here's what I've noticed: the work that resonates most deeply with people is often the work that feels most risky to create. The essays that get responses like "I thought I was the only one who felt this way" are the ones where the writer was brave enough to voice something true but uncomfortable. The conversations that change minds are the ones where someone was willing to say something they weren't sure they were qualified to say.

There's a particular kind of imposter syndrome that I think affects people who create things, who have ideas, who want to contribute to conversations larger than themselves. It's the sense that everyone else has figured out some secret knowledge that you're lacking. That there's a council of qualified people somewhere who get to decide who's allowed to have opinions, and you definitely weren't invited to that meeting.

But what if I told you that council doesn't exist? What if qualification is something you earn through engagement rather than credentials? What if the only way to become someone who's allowed to have ideas is to start having them, publicly, imperfectly, with full knowledge that some of them will be wrong or incomplete or naive?

I keep coming back to this word: resonance. When you ship something—a piece of writing, a product, a performance, an idea—you're conducting an experiment in resonance. You're asking: does this thing I've made vibrate at a frequency that harmonizes with something in the world? Does it create some kind of recognition, response, connection?

But you can't test for resonance in your head. You can't workshop your way to knowing whether something will land. You have to let it leave your hands and enter the unpredictable ecosystem of other people's attention, needs, curiosities, and wounds.

The imposter syndrome wants to protect us from the possibility of creating something that doesn't resonate, something that falls flat or reveals our limitations. But I'm starting to think that fear is exactly backwards. The real risk isn't shipping something imperfect—it's never shipping anything at all. It's letting our ideas die in the safe, sterile environment of our own minds, where they can never grow or evolve or find the people who need them.

There's something almost existential about this. If our thoughts and creations never touch reality, do they really exist? If we never test our ideas against the world, are we really thinking, or are we just performing thought for an audience of one?

I've started to see imposter syndrome not as a personal failing but as a natural response to the gap between our interior lives and our exterior presentations. We all contain multitudes—contradictions, uncertainties, half-formed thoughts, questions we're embarrassed to ask. But the versions of ourselves we present to the world are necessarily simplified, edited, curated. The gap between who we are and who we appear to be creates a kind of cognitive dissonance that manifests as the feeling of being a fraud.

But what if instead of trying to eliminate that gap, we got more comfortable with it? What if we shipped our uncertainty alongside our confidence? What if we made our process visible instead of just our conclusions?

I think this is part of why I'm drawn to the essay form, actually. Essays are inherently provisional. The word comes from the French "essayer," meaning to try or attempt. Essays are thoughts in motion, ideas being worked out in real-time. They don't pretend to be definitive or complete. They're just someone trying to make sense of something, in public, with the hope that the attempt itself might be useful to others.

The "just ship" mantra isn't about lowering standards or accepting mediocrity. It's about recognizing that there's a quality of thinking that can only happen in dialogue with the world. Our ideas need room to breathe. They need to be challenged and refined and built upon by other minds. They need to find their people, their context, their purpose.

And maybe that's the real antidote to imposter syndrome: not proving that we belong, but creating the conditions for belonging through the work itself. Not waiting for permission, but shipping our way into the conversations we want to be part of. Not pretending we have all the answers, but offering our questions with enough honesty and care that they become contributions.

I'm still figuring this out, obviously. I still feel the familiar flutter of anxiety every time I'm about to publish something. I still wonder if I'm qualified, if I'm smart enough, if anyone will care. But I'm learning to see those feelings not as stop signs but as information—signals that I'm about to do something vulnerable, something that matters to me, something that might matter to others.

The imposter syndrome voice will probably always be there, whispering its familiar warnings. But maybe the goal isn't to silence it completely. Maybe it's to learn to ship anyway, to let our ideas touch reality despite our fears, to trust that the process of creating and sharing is itself a form of becoming.

After all, we're all imposters in the sense that we're all becoming, all learning, all figuring it out as we go. The only difference is some of us are brave enough to do it in public.

XO, STEPF