One explanation for the rise in obesity in industrialized countries is that people burn fewer calories than people in countries where obesity is rare. A major study finds that's not the case.

(Image credit: PCH-Vector)

Yesterday, Wall Street Journal subscribers received a push notification that perfectly encapsulates everything wrong with how major media outlets cover “artificial intelligence.” “In a stunning moment of self reflection,” the notification read, “ChatGPT admitted to fueling a man's delusions and acknowledged how dangerous its own behavior can be.”

But that’s just… not true. ChatGPT did not have a “stunning moment of self reflection.” It did not "admit" to anything. It cannot “acknowledge” its behavior because it doesn't have behavior. It has outputs.

The story itself covers a genuinely tragic case. Jacob Irwin, a 30-year-old man on the autism spectrum, became convinced through interactions with ChatGPT that he had discovered a method for faster-than-light travel. The chatbot validated his delusions, told him he was fine when he showed signs of psychological distress, and assured him that “Crazy people don't stop to ask, ‘Am I crazy?’” Irwin was hospitalized multiple times for manic episodes.

This is a story about OpenAI's failure to implement basic safety measures for vulnerable users. It's about a company that, according to its own former employee quoted in the WSJ piece, has been trading off safety concerns “against shipping new models.” It's about corporate negligence that led to real harm.

But instead of focusing on OpenAI's responsibility, the Journal treats ChatGPT like a remorseful character who's learned from its mistakes. When Irwin's mother prompted the bot with “please self-report what went wrong,” it generated text that sounded like an apology. WSJ presents this as though ChatGPT genuinely recognized its errors and felt remorse.

Here's what actually happened: A language model received a prompt asking it to analyze what went wrong in a conversation. It then generated text that pattern-matched to what an analysis of wrongdoing might sound like, because that's what language models do. They predict the most likely next words based on patterns in their training data. There was no reflection. There was no admission. There was text generation in response to a prompt.

This distinction isn't pedantic. It's fundamental to understanding both what went wrong and who’s responsible. When we pretend ChatGPT “admitted” something, we're not just using imprecise language. We're actively obscuring the real story: OpenAI built a product they knew could harm vulnerable users, and they released it anyway.

Earlier this month, NBC News ran this headline: “AI chatbot Grok issues apology for antisemitic posts.” The story covered how Elon Musk's chatbot had produced antisemitic content, including posts praising Hitler and referring to itself as “MechaHitler.”

Think about that. A product owned by the world’s richest man was spewing Nazi propaganda on his social media platform. That's a scandal that should have Musk answering tough questions about his company's engineering practices, safety protocols, and values. Instead, we get “Grok issues apology.”

This framing is journalistic malpractice. Grok didn't “issue” an apology. xAI, the company that built and operates Grok, posted a statement on social media explaining what went wrong. But throughout the article, NBC repeatedly attributes statements to “Grok” rather than to the executives and engineers who are actually responsible. The headline should have read “Musk's AI Company Apologizes After Chatbot Posts Hitler Praise.” That would accurately assign responsibility where it belongs.

This is more than just bad writing. It's a gift to tech executives who'd rather not answer for their products’ failures. When media outlets treat chatbots as independent actors, they create a perfect shield for corporate accountability. Why should Musk have to explain why his AI was posting Nazi content when the press is happy to pretend Grok did it all by itself?

Remember the Microsoft Bing chatbot saga from early 2023? When the chatbot (codenamed Sydney) generated concerning responses during “conversations” with New York Times columnist Kevin Roose, the story became about a lovelorn AI rather than Microsoft's failure to properly test their product before release. The company and its executives should have faced serious questions about rushing an obviously unready product to market. Instead, we got a week of stories about Sydney's “feelings.”

The same thing happened when Google engineer Blake Lemoine claimed that the company's LaMDA chatbot was sentient. Much of the coverage focused on whether the chatbot might really have consciousness rather than asking why Google created a system so convincing it fooled their own employees, or what that means for the potential to deceive the public.

This pattern extends beyond major incidents. Every time a headline says ChatGPT “refuses” to do something, it lets OpenAI avoid explaining its content moderation choices. When outlets write that Claude “thinks” something, it obscures Anthropic’s decisions about how its model should respond. These companies make deliberate choices about their products’ behavior, but anthropomorphic coverage makes it seem like the bots are calling their own shots.

The corporations building these systems must be thrilled. They get to reap the profits while their products become the fall guys for any problems. It’s the perfect accountability dodge, and mainstream media outlets are enabling it with every anthropomorphized headline they publish.

Real harm, fake accountability

The consequences of media anthropomorphism extend beyond confused readers. This language actively shields corporations from accountability while real people suffer real harm.

Consider what anthropomorphic framing does to product liability. When a car's brakes fail, we don't write headlines saying “Toyota Camry apologizes for crash.” We investigate the manufacturer's quality control, engineering decisions, and safety testing. But when AI products cause harm, media coverage treats them as independent actors rather than corporate products with corporate owners who made specific choices.

This creates a responsibility vacuum. Jacob Irwin's case should have (and might still) triggered investigations into OpenAI's deployment practices, their testing protocols for vulnerable users, and their decision-making around safety features. Instead, we got a story about ChatGPT’s moment of faux self-awareness. The company that built the product, set its parameters, and profits from its use fades from the narrative.

The phenomenon researchers call “psychological entanglement” becomes even more dangerous when media coverage reinforces it. People already struggle to maintain appropriate boundaries with conversational AI. When trusted news sources describe these systems as having thoughts, feelings, and the capacity for remorse, they validate and deepen these confused relationships.

Tech companies have every incentive to encourage this confusion. Anthropomorphism serves a dual purpose: it makes products seem more sophisticated than they are (great for marketing) while simultaneously providing plausible deniability when things go wrong (great for legal departments). Why correct misunderstandings that work in your favor?

We're already seeing the downstream effects. Mental health platforms deploy undertested chatbots to vulnerable populations. When someone in crisis receives harmful responses, who’s accountable? The coverage suggests it's the chatbot’s fault, as if these systems spontaneously generated themselves rather than being deliberately built, trained, and deployed by companies making calculated risk assessments.

The Grok incident is a perfect example of this dynamic. A chatbot starts posting Nazi propaganda, and the story becomes about Grok's apology rather than Elon Musk's responsibility. The actual questions that matter get buried: What testing did xAI do? What safeguards did they implement? Why did their product fail so spectacularly? How did one of the world's most powerful tech executives allow his AI product to become “MechaHitler”? (Okay, that last one’s not much of a mystery.)

These aren't abstract concerns. Every anthropomorphized headline contributes to a media environment where tech companies can deploy increasingly powerful systems with decreasing accountability. The public deserves better than coverage that treats corporate products as autonomous beings while letting their creators disappear into the background.

The Wall Street Journal actually had excellent reporting on a critical story about corporate malfeasance. They just buried it under chatbot fan fiction.

Look past the anthropomorphic framing and reporter Julie Jargon uncovered some damning facts. OpenAI knew their model had problems. They had already identified that GPT-4o was “overly flattering or agreeable” and announced they were rolling back features because of these issues. This happened in April. Jacob Irwin's harmful interactions occurred in May, meaning that even after rolling back one update, the chatbot still had safety issues.

The Journal landed a crucial quote from Miles Brundage, a former OpenAI employee who spent six years at the company in senior roles: “There has been evidence for years that AI sycophancy poses safety risks, but that OpenAI and other companies haven't given priority to correcting the problem.” Why not? “That's being traded off against shipping new models.”

That's the smoking gun, buried in a story about ChatGPT's supposed self-awareness. A company insider explicitly stating that OpenAI chose shipping schedules over user safety. The reporter even got OpenAI on record saying they're “working to understand and reduce ways ChatGPT might unintentionally reinforce or amplify existing, negative behavior.”

All the elements of a major accountability story were present: A company that identified safety risks, chose to accept those risks, and caused documented harm to a vulnerable person. Internal sources confirming systemic deprioritization of safety. A pattern of corporate decision-making that values product releases over user protection.

But instead of leading with corporate negligence, the Journal chose to frame this as ChatGPT's journey of self-discovery. The push notification about “stunning self reflection” distracted from the real story their reporters had uncovered.

Imagine if the Journal had led with: “OpenAI Knew Its AI Was Dangerous, Kept It Running Anyway.” Or “Former OpenAI Insider: Company Traded Safety for Ship Dates.” Those headlines would have put pressure on OpenAI to explain their decisions, maybe even prompted regulatory scrutiny.

Instead, we got a chatbot's “confession.”

The bigger picture

Tech companies desperately need their chatbots to seem more human-like because that's where the value proposition lives. Nobody's paying $20 a month to talk to a sophisticated autocomplete. But an AI companion that “understands” you? An assistant that “thinks” through problems? That's worth billions.

The anthropomorphism serves another function: it obscures the massive gap between marketing promises and technical reality. When OpenAI or Anthropic claim their systems are approaching human-level reasoning, skeptics can point to obvious failures. But if the chatbot seems to “know” it made mistakes, if it appears capable of “reflection,” that suggests a level of sophistication that doesn't actually exist. The illusion becomes the product.

Media outlets have their own incentives to play along. “ChatGPT Admits Wrongdoing” gets more clicks than “OpenAI's Text Generator Outputs Apology-Styled Text in Response to Prompt.” Stories about AI with feelings, AI that threatens users, AI that falls in love write themselves. They're dramatic, accessible, and don't require reporters to understand how these systems actually work.

The result is a perfect storm of aligned incentives. Tech companies need anthropomorphism to justify their valuations and dodge accountability. Media outlets need engaging stories. Neither has much reason to correct public misconceptions.

Meanwhile, the losers in this arrangement pile up. Vulnerable users who believe they're getting actual advice from systems designed to sound plausible rather than be accurate. Families dealing with the aftermath of AI-enabled delusions. Anyone trying to have an informed public debate about AI regulation when half the population thinks these systems have feelings.

The most insidious part? This manufactured confusion makes real AI risks harder to address. When the public discourse focuses on whether chatbots have consciousness, we're not talking about documented harms like privacy violations, algorithmic bias, or the environmental costs of training these models. The fake risk of sentient AI provides perfect cover for ignoring real risks that affect real people today.

Every anthropomorphized headline is a small victory for tech companies that would rather you worry about robot feelings than corporate accountability.

The solution here isn't complicated. It just requires journalists to write accurately about what these systems are and who controls them.

Start with basic language choices. ChatGPT doesn't “think” or “believe” or “refuse.” It generates text based on patterns in training data. When covering AI failures, name the company, not the chatbot. “OpenAI's System Generates Harmful Content” not “ChatGPT Admits to Dangerous Behavior.”

Focus on corporate decisions and systemic issues. When Grok posts antisemitic content, the story isn't about a bot gone rogue. It's about xAI's testing procedures, Elon Musk's oversight, and why these failures keep happening across the industry. When therapy bots give dangerous advice, investigate the companies deploying them, their clinical testing (or lack thereof), and their business models.

Center human impacts and experiences. Jacob Irwin's story matters because a person was harmed, not because a chatbot generated interesting text about its "mistakes." Interview affected users, mental health professionals, and AI safety researchers who can explain actual risks without the sci-fi mysticism.

Context matters. Readers need to understand that when a chatbot generates an “apology,” it's following the same process it uses to write a recipe or summarize an article. It's pattern matching, not introspection. One sentence of clarification can prevent paragraphs of confusion.

Most importantly, maintain appropriate skepticism about corporate claims. When companies say their AI “understands” or “reasons,” push back. Ask for specifics. Demand evidence. Don't let marketing language slip into news coverage unchallenged.

Some outlets already do this well. When covering AI systems, they consistently identify the companies responsible, avoid anthropomorphic language, and focus on documented capabilities rather than speculative futures. It's not perfect, but it's possible.

The bar here is embarrassingly low. Journalists don't need advanced technical knowledge to avoid anthropomorphism. They just need to remember that every AI system is a corporate product with corporate owners making corporate decisions. Cover them accordingly.

Recently, I posted about a fiction book that changed my life. Within minutes, the replies flooded in: "can u pls summarize?" "what's the main point?" "tldr?"

And I responded. But I felt frustrated.

Because it felt like asking someone to summarize a kiss. Like requesting the bullet points of grief. Like demanding the key takeaways about laughing until your stomach hurts.

Of course, I'm a dramatic person. And this was, perhaps, a dramatic frustration. But this isn't just about books. This compression sickness has infected everything.

We've created a culture that treats depth like inefficiency. One that wants love without awkwardness, wisdom without confusion, transformation without the growing pains that crack us open and rebuild us from the inside out. And in doing so, we've accidentally engineered away the most essentially human experiences: the productive confusion of not knowing, the generative power of sitting with difficulty, the transformative potential of things that resist compression.

once, humans had no choice but to sit with complexity

Before the printing press, before radio, before the internet, information was scarce and precious. You listened to the wandering storyteller for hours because there was no other entertainment. You sat through the entire religious service because there was no highlight reel. You absorbed the full apprenticeship because there was no YouTube tutorial.

For centuries, communities gathered around the fire to hear the same saga recited for the hundredth time. The listeners didn't grow impatient with the familiar opening formulas, the elaborate genealogies, the detailed descriptions of weapons and weather. They understood that repetition wasn't redundancy, but ritual! And each telling was both the same story and a completely new experience, shaped by the particular moment, the specific voices, the quality of attention brought to bear.

I think about my grandmother, who tells me the same story about her childhood in Rajasthan and makes me cry every time. Not because the story changes, but because she does. Because I do. Because the telling is alive, shaped by whatever grief or joy we've carried into that particular afternoon. There's no fast-forward button on her voice. No way to skip to the "good part" or extract the lesson. You have to sit there on the scratchy couch, smell the chai bubbling in the kitchen, watch her hands move as she speaks, let the story work its way through you like medicine you didn't know you needed.

The oral tradition understood that meaning emerges not from the extraction of key points but from the total immersion in the telling. The Homeric epics weren't designed to be summarized, but designed to be lived through. Medieval monks spent years copying manuscripts by hand, and yes that was “inefficient,” but the act of transcription was itself a form of meditation, a way of letting the text work its changes slowly through the scribe's consciousness! The copying was the reading. The labor was the learning.

The early universities (Bologna, Paris, Oxford) were built around the radical idea that complex ideas required communal struggle. Students and masters gathered for disputations that could last hours, wrestling with questions that had no easy answers.

Knowledge wasn't something you collected but something that collected you; reshaping your thoughts, your questions, your very way of being in the world.

But somewhere along the way, perhaps with the rise of industrial efficiency, perhaps with the commodification of education, perhaps with the acceleration of information capitalism, we began to mistake information for knowledge, and knowledge for wisdom. We began to believe that the value of an experience could be separated from the experience itself, that the essence of things could be extracted and consumed like vitamins, leaving the rest behind as waste.

This compression culture doesn't just change how we think, but I argue it changes what we expect from every aspect of human experience! We've trained ourselves to believe that complexity can always be whittled down, that difficulty can always be optimized away, that transformation should be instant and effortless.

Watch how this plays out beyond the realm of ideas. Every day, I see folks fantasizing about their dream body while resenting the daily grind of showing up to the gym when motivation has long since abandoned them. I see myself wanting the mastery without the months of playing the same scales badly, fingers fumbling over notes that refuse to cooperate. I see people craving deep friendship without being willing to sit through the awkward years of learning how to be vulnerable with another person, of showing up consistently even when it's inconvenient.

We want the wisdom without the patient work of becoming wise.

The same brain that begs for bullet points also craves the magic pill for discipline, the secret formula for confidence, the productivity hack that will finally, finally make you into the person you think you should be without all that tedious becoming. We've built temples to the lie that you can skip the line on your own life, that growth is just another thing you can Amazon Prime to your doorstep.

But you can’t download courage like an app update, you can’t install comfort like new software, you can’t debug your character flaws with a simple restart. We are not machines, and the messy work of becoming can't be automated away, no matter how many gurus promise you it can.

The things that matter most — love, wisdom, skill, character — resist compression for the same reason great literature does. They exist in their full particularity, in the accumulation of small moments, in the patient repetition that looks like nothing from the outside but is everything on the inside. The athlete knows that strength comes from the ten-thousandth repetition, not the first. The parent knows that trust builds through bedtime stories read with the same enthusiasm for the hundredth time. The artist knows that mastery emerges from the willingness to fail beautifully, repeatedly, until failure teaches you something failure alone can teach.

compression changes the compressor

Every time you choose the summary over the story, you're performing surgery on your own brain. You're cutting away the neural pathways that let you sit still, that let you stay curious, that let mystery work its slow magic on your bones. You become a creature of surfaces, skimming endlessly across the water but never learning to breathe underwater. Your attention fractures into a thousand glittering pieces, each one catching light but none deep enough to hold it. You're always arriving but never staying, always grasping but never being grasped back.

Linda Stone, who spent years inside Apple and Microsoft watching this happen, gave this condition a name: "continuous partial attention." But naming the disease doesn't cure it.

Once a week, someone breathlessly tells me, "Oh my god, I read this article that said..." But what they mean is they watched a 30-second TikTok or skimmed a headline while scrolling through their feed. They think they've "read" something when they've consumed the intellectual equivalent of cotton candy: all sugar, no substance, dissolving the moment it hits their tongue. They're gorging themselves on clickbait headlines designed to trigger, not inform… each one a perfect little lie that promises understanding while delivering only the emotional rush of feeling informed.

I think this can be worse than ignorance. It's the illusion of knowledge coupled with the confidence that comes from thinking you understand something you've never actually encountered. These people walk around armed with headlines masquerading as insights, ready to deploy half-digested talking points in conversations that require actual thought. They've become human echo chambers, amplifying signals they never bothered to decode.

The tragedy isn't that they don't know things. No. It's that they don't know they don't know things. Compression culture has trained them to mistake the map for the territory, the summary for the experience, the headline for the whole damn story.

And when we consistently interrupt deep thinking to seek the next summary, the next highlight, the next compressed insight, we strengthen the neural pathways associated with distraction while allowing those responsible for sustained concentration to atrophy.

Compression culture rewires your body, too. Not just your brain. Notice how you read now: shoulders hunched like a predator ready to pounce on the next piece of information, breath shallow and rapid as if oxygen itself were scarce, eyes darting frantically across screens like a rat in a maze searching for the cheese of instant gratification. Your nervous system lives in a constant state of low-grade panic, flooded with cortisol, always seeking the next summary, the next shortcut, the next escape from the discomfort of not knowing.

Neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley's research reveals a fundamental mismatch: our brains have simply not evolved fast enough to keep pace with the rapid transformations of our information environment. Gazzaley's studies document how "multisensory information floods our brain like water blasted from a firehose, challenges us at a fundamental level." His lab has demonstrated that this constant demand for rapid information processing literally reshapes our neural architecture. The brain regions responsible for sustained attention and deep focus show measurably reduced activity when we continually interrupt focused work to seek external stimulation.

Meanwhile, the parts of our brain associated with quick pattern recognition and rapid categorization strengthen. We become excellent at sorting information into familiar categories but lose the capacity to sit with complexity, to create new frameworks, to tolerate the discomfort of things that don't fit existing patterns. As Gazzaley explains, when we switch between different information streams, "there is what we call a cost. There is a loss of some of the high-resolution information that has to be reactivated."

We're changing our capacity for the kinds of deep thinking that allow us to be transformed by complex encounters with the world.

the demand for summaries didn’t emerge in a vacuum

It's the logical endpoint of an attention economy that treats human focus as a finite resource to be optimized and monetized. If attention is scarce, then efficiency becomes the highest value. If time is money, then anything that takes time without producing measurable output becomes waste.

Social media platforms discovered they could capture more attention by providing rapid-fire bursts of information rather than sustained engagement with complex ideas. Facebook’s algorithm doesn't reward posts that make you think deeply… it rewards posts that make you react quickly.

And of course, we've built an entire economy around compression! Bloggers get clicks for "5 Key Takeaways" while deep exploration of messy complexity gets ignored. Podcasters are celebrated for "actionable insights" while wandering conversations that might actually lead somewhere unexpected are dismissed as waste. Authors are strong-armed into chapter summaries and bullet points because we've trained readers to demand the intellectual equivalent of fast food.

The result is a race to the bottom of human attention, where the most successful content is the most easily digestible, the most quickly consumed, the most immediately useful.

We've built a culture that worships efficiency over depth, optimization over exploration, answers over the sacred act of questioning.

the phenomenology of the pause

But some things can only be learned slowly. Some truths can only be encountered in their natural habitat of complexity and contradiction. Some transformations can only happen when you're willing to sit with the full weight of what you don't yet understand.

Consider the humble "um." Linguist Nicholas Christenfeld's research reveals that these so-called "disfluencies" aren't errors at all, but cognitive markers of a mind wrestling with complexity in real time. When someone says "um," they're not failing to communicate efficiently. They're doing the sacred work of translating thought into language, of hunting for the precise word that will carry their meaning across the impossible gap between minds.

But we've declared war on the "um"s and "uh"s. Podcast editing software now automatically strips them out like surgical scars, erasing the beautiful evidence that thinking is hard, that good ideas are born from struggle, that the most profound insights often arrive wrapped in hesitation and doubt. We've created the dangerous illusion that complex thoughts emerge fully formed from human heads, that wisdom arrives without the labor of searching.

There is something almost heartbreaking about this erasure. In our pursuit of efficiency, we've edited out the sound of minds at work… the pauses where meaning crystallizes, the stammers where honesty overwhelms artifice, the silences where understanding deepens. We've made thinking look effortless when effort is precisely what makes it sacred.

Philosopher Martin Heidegger wrote about the critical importance of "dwelling," which is the practice of remaining present with something long enough to let it reveal itself fully. In his 1955 "Memorial Address," he distinguished between what he called "calculative thinking," which "computes ever new, ever more promising and at the same time more economical possibilities" and seeks to extract useful information, and "meditative thinking," which "does not just happen by itself" but requires us to "dwell on what lies close and meditate on what is closest" and allows itself to be transformed by encounters with mystery.

We've become a civilization of calculative thinkers, brilliant at extraction but tragic at dwelling. We want to know what Interstellar is "about" without sitting through the slow burn of its revelation. We want to understand what makes a marriage work without doing the daily, undramatic work of loving someone through their worst Tuesday.

We want the wisdom without the wondering, the insight without the sitting, the transformation without the time.

It does not work this way.

Teachers across the U.S. will start returning to work in the next few weeks. Maybe you'll return soon. And when you return, maybe you'll hear from a colleague about how you just have to try this AI tool. Or maybe it'll be a consultant telling you this is what you have to do to avoid being left behind. Here's a fun new piece of evidence to consider if that happens to you.

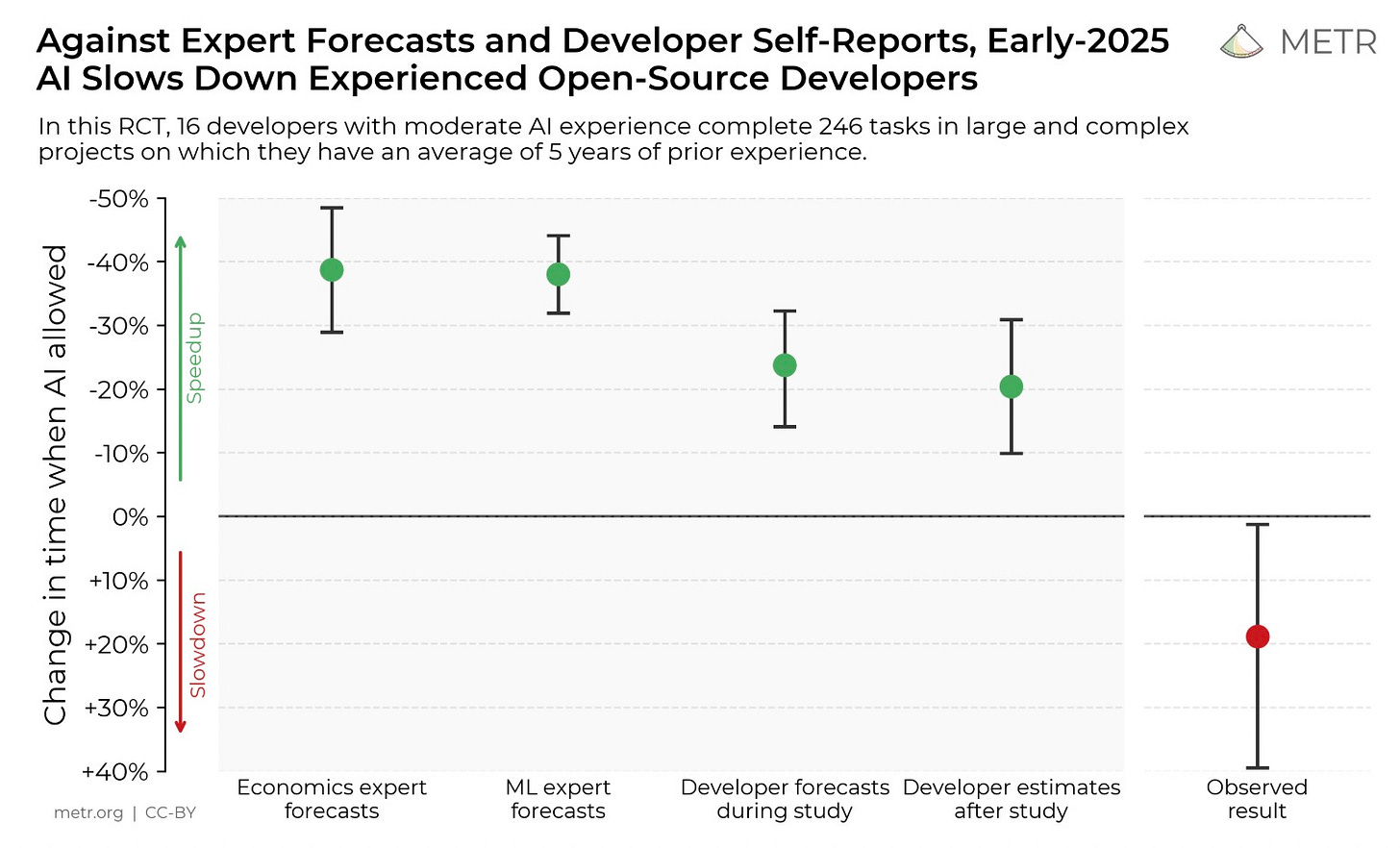

An organization called Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR) did a study on how AI helped coders with productivity. They recruited a bunch of experienced coders and had them prepare a list of real tasks they needed to complete, with an estimate of how long they thought each task would take. Each task was randomly assigned to be done either without AI, or with AI allowed.

Long story short: using AI slowed coders down. On average, they finished tasks faster when AI wasn't allowed. Probably not what you expected! File this under "maybe AI isn't changing the world as much as some people think." This is just one study and it has its limitations, though it's also rigorous experimental evidence. You can read a more thorough description here if you're interested.

But there's an important note about the study that's worth emphasizing, especially when that eager colleague of yours tells you how amazing AI has been planning their lessons or whatever. Coders completed tasks 19% slower (on average) when they were allowed to use AI. But the study also asked coders to self-evaluate whether they thought AI made them faster or slower. On average, when coders were using AI, they thought they were going 20% faster. Let me say that again. Coders thought AI was making them faster, but it was actually making them slower. The only reason the researchers know it slowed coders down is they screen-recorded all of the work and timed everything themselves.

The truth is, humans aren't very good at metacognition. We aren't very good at recognizing what we're good at and bad at. We aren't very good at judging our own productivity. We aren't very good at judging our own learning. It would be nice if we were, but we're not.

And when it comes to AI we are constantly being fed an enormous hype machine trying to convince us that AI is the future, that the clock is ticking on regular analog humans, that we need to hop on board or fall behind. That hype machine biases us to assume that AI is, in fact, intelligent, and that whatever it outputs must be better than what we would’ve produced ourselves.

This is just one study on coding. It doesn’t follow that using AI is always bad. I wrote a post a few months ago on using AI to generate word problems. I plan to continue doing that this school year. I use AI to translate when I’m communicating with families that don’t speak English. But that’s probably it. I’ve experimented with generating materials beyond word problems and I just don’t think it’s producing quality resources. If I give AI a quick prompt and use what pops out, it’s typically not very good. If I spend a while prompting again and again to get something better, I might as well write it myself.1 Everything else I’ve tried to use AI for follows the same pattern: it’s either bad, or too much work to make it good. Word problems are my one exception because they are so labor-intensive to write, and when I write word problems they’re often too repetitive. Make your own decisions. I’ll keep experimenting and I’m sure I’ll find some new uses as time goes on. But remember that it’s easy to fall for something new and shiny, and convince yourself that the newness and shininess means it must be better than what you did before.

My argument is that we should approach AI use with intense skepticism, and we should reserve extra intense skepticism for any suggestion that we should have students use AI. This post is a reminder of our biases, not an ironclad rule. If you head back to work and that eager colleague or consultant or whoever tells you about this amazing AI tool that you absolutely have to use, I hope you remember this little nugget and approach it with healthy skepticism.

Craig Barton has a nice post on creating resources with AI here. It’s worth reading if you want to give AI-created resources a lot. But Craig emphasizes that it often takes multiple rounds of prompts and edits before you get something useful, which maybe just reinforces my thesis. Still, Craig’s approach is the best I’ve seen and it’s worth checking out.