This post is greatly inspired by the awesome article The Federation Fallacy by Alyssa Rosenzweig. Please make sure to check her out. Some of the ideas discussed here today are greatly inspired by the original post, bearing the same name.

Imagine this: the boundary between government control and corporate influence has all but disappeared. One bleeds into the other so seamlessly that you can't quite tell who's pulling the strings. And here's the kicker---you're already in the middle of it. Every time you unlock your phone, launch an app, or just exist online, you're stepping onto a battleground you didn't really sign up for.

I missed a great portion of the technological advancements that computers and the internet went through. I was blissfully offline throughout most of it. Although now that I have been diving more into OSdev and other programming concepts, my understanding of it is that technology was supposed to be the great equalizer. A tool for freedom, connection, progress. Instead, it appears to have become something else entirely---something much more insidious. Governments no longer need to strong-arm their citizens into compliance when corporations can do the dirty work for them. And the best part? Most people, perhaps even you reading this, don't even notice. The social contract didn't just get rewritten; it got outsourced.

But here is where things take a turn. The same technology used to monitor, categorize, and manipulate us also holds the potential to set us free. The internet, encryption, decentralized platforms—these aren't just tools, they are weapons in a fight most people don't even realize they're a part of. And that's the problem. Too many of us engage with technology passively, as consumers and not as participants. We think of it as a service, not a structure of power. That is a monumental mistake. 1

Take something as basic as data ownership. Who owns your data? The reflexive answer might be, "I do, obviously." But think about it for a second. The moment you tap "Agree" on a terms-of-service agreement you didn't read, you're giving away more than you think. Your habits, your movements, maybe even your thoughts---logged, analyzed, and monetized by entities that have no obligation to you in ways that would not occur to you in your wildest dreams. And here is the brutal truth: once it's gone, it's gone. You don't get to take it back.

Now, let's talk about digital sovereignty. Sounds like something ripped from a cyberpunk novel, but it's real, and it matters. You might have not heard of it before, and frankly I have not thought much of it until my research brought me across several sources that used the term. It is the idea that individuals---and entire nations---should control their digital presence the way they control their physical borders. It is about deciding who gets access to your identity, on what terms, and with what consequences. Yet, somehow, this is is not a mainstream political discussion. We act like it is a niche concern, something for tech nerds to stress about, instead of what it really is---a fundamental issue of power in the 21st century.

Interlude: On Data Ownership

While working on this post, I was reminded several times that in some countries data ownership is, in fact, a mainstream political discussion. I am aware of this, and I really admire the level of optimism required to believe this is somehow the case for an acceptable majority. It isn't. According to Freedom House Freedom on the Net 2020 report, over 80% (the actually cited number is 86%, and I fear it has gotten worse by now) of the world's population live in in regimes where the online participation is partially or fully censored. What is the possibility that most of us own the data when most of us cannot go online without our every move being recorded?

Some European countries have been making extended efforts to ensure privacy as a right, other continents have been regressing steadily. The United States has granted unlimited access to every citizen's data to a private citizen while in Turkiye, the government has decided to form a government department to monitor and act on online activity with little to no regulation. This kind of immense censorship is also the case in China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and many more that I can count. Whatever privacy incentive you might be aware of is not the norm, nor is it setting an example for the rest of us. This is quite unfortunate, yet not at all surprising. One of the many dimensions of a state is to express power.

Federation Fallacy: Continued

Make no mistake, this is about power. Data is the raw material of modern power, the foundation upon which influence, control, and wealth are built. Those who have it shape the world. The problem? Governments and corporations have been playing this game for decades, and while you are barely of the rules, they have mastered it. The most average player of the game can barely remember their own passwords, let alone having any awareness of the game.

So what now? What do we do with this knowledge? First, we need to accept that technological literacy isn't optional anymore---it is survival. Second, resistance doesn't always mean taking to the streets, or drawing graffiti on walls. Sometimes, it is as simple as using open-source software, encrypting your messages, or just stopping for a moment to ask, "Why does it have to be this way?" The final step? That's on you. But let me be very clear: doing nothing is a choice, and it has consequences. Costly consequences.

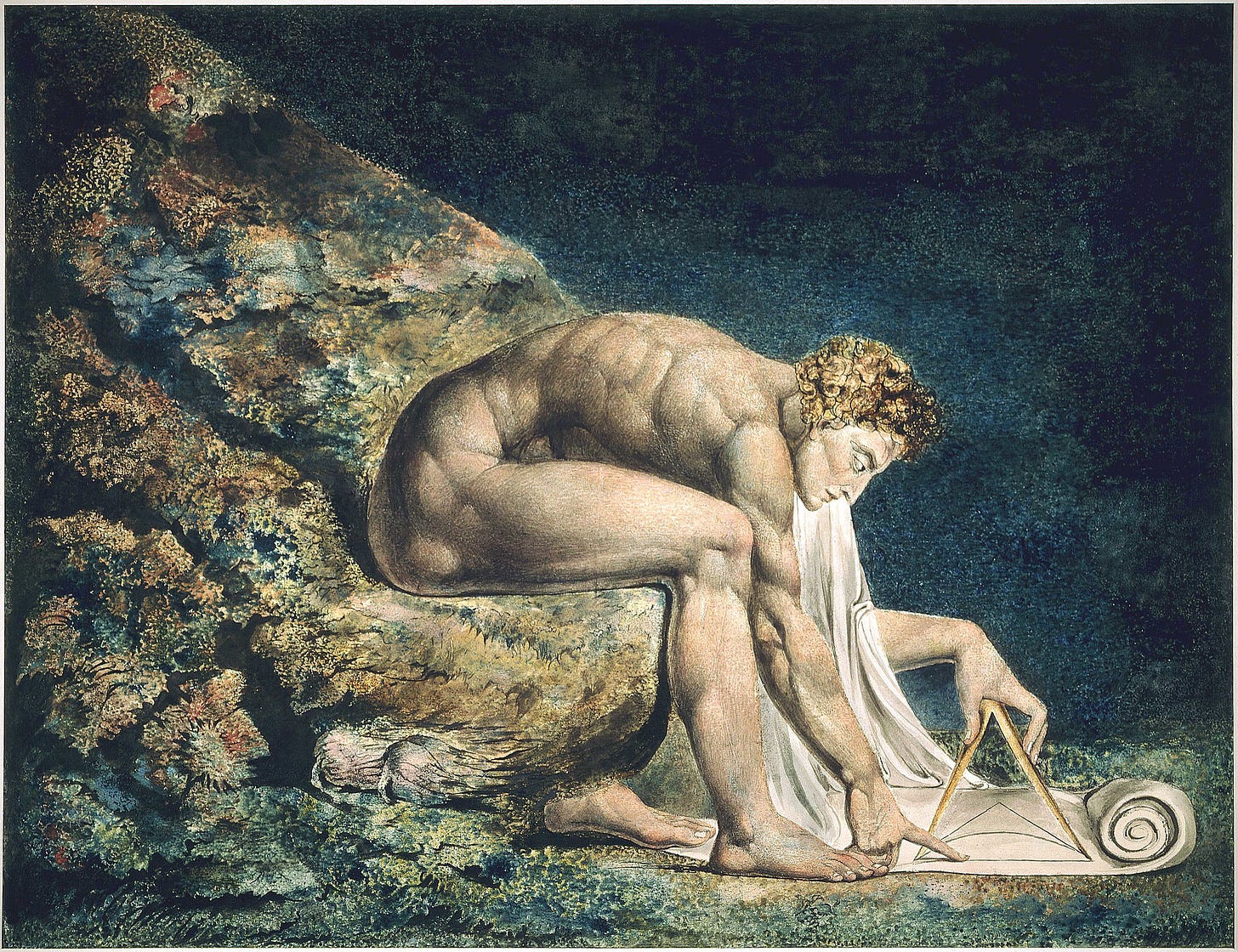

We happen to be at a turning point. The choices we make now--about technology, governance, and personal autonomy--will shape the next century. The only question is: will we be the architects of that future? Or just subjects to it?

Federation: The False Promise of Decentralization

You might have heard of the promise of decentralization, an ideal where the power and control of the digital world are distributed evenly, away from the corporate giants and government entities that currently dominate. Many of us in the open-source and privacy communities dream of this decentralized world. We envision a future where individuals can host their own servers, own their data, and share information freely, without intermediaries like Google, Amazon, or Facebook controlling the flow.

But the reality of decentralized networks, such as federated platforms like Mastodon or the once-promising web, exposes a serious flaw in this vision. Sure, decentralization sounds like the solution to the problem of monopolistic control. But let me break it down. Decentralization isn't as simple as just opening a server and letting users do whatever they want. If you think about it, decentralization often becomes a highly technical and impractical solution for the majority. Most people aren't system administrators. They don't want to host their own email servers, 2 handle constant updates, or manage security vulnerabilities. And let's be honest: it is not something most will do. So what happens? The dream of decentralization becomes a playground for the technologically "elite," and the rest of us are left either uninvolved or stuck relying on others to handle the complexity for us.

Federation attempts to solve this issue by allowing individuals or groups to host their own servers while still communicating with others across the network. Unlike a fully decentralized system where each user is entirely independent, a federated system connects multiple independent servers that can exchange data while maintaining local control. The idea behind federated platforms like Mastodon is that you can join or create independent instances and still interact with users across the wider network, much like how different email providers (Gmail, Outlook, etc.) can send messages to each other. This approach avoids the need for a single central authority while still enabling cross-platform communication.

Federation seems like a happy medium between full decentralization and reliance on centralized corporate platforms. But it comes with its own problems. Despite the ideal of decentralization, federated systems have shown a tendency to concentrate power into the hands of a few large instances. While there may be thousands of Mastodon instances, the majority of users end up clustering around a few, leaving power and control in the hands of administrators who run these larger servers. 3

Take Mastodon, for instance. It promises a decentralized, federated alternative to X/Twitter, where users are free to join different servers and interact across a network. But in practice, most people gravitate toward a handful of large instances, making the system feel centralized. The same problem plagues email, XMPP, and even the original decentralized web: while the systems themselves are designed to be federated, the reality is that scale and complexity inevitably lead to centralization. These federated systems are still subject to the whims of a few large players, who end up determining the experience for most users.

So, what does this mean for the dream of decentralization? It means that federation, despite its merits, often falls short of its ideal. It is an imperfect middle ground that tries to balance decentralization with practicality. But as the user base grows, so does the tendency for power to centralize; just in different ways.

Perhaps the solution lies not in decentralization for its own sake but in creating more democratic information spaces. Rather than solely focusing on breaking free from the power of corporations or governments, we must ask: how can we create systems where the power is distributed fairly, transparently, and with participation from all users, not just the elites who can afford to manage complex systems? Ultimately, decentralization and federation offer only partial solutions. The real goal should be creating systems that empower individuals while maintaining the democratic oversight necessary to prevent concentration of power. The dream of a decentralized future may be far from perfect, but it's not impossible. The question is, how do we design it in a way that is inclusive, scalable, and fair to all?

Closing Thoughts

Even as decentralized networks and cryptographic tools emerge as potential solutions, they strike me as far from perfect. The very technologies that promise to free us from corporate and governmental oversight are also fraught with their own limitations and vulnerabilities. Decentralization, for instance, sounds like the answer to control over one's data, yet it introduces new risks--fragmentation, inconsistent security protocols, and the lack of cohesive infrastructure. 4 As much as we crave autonomy, it's difficult to ignore that true digital sovereignty may require us torely on infrastructure that is, ironically, still controlled by large tech entities. Peer-to-peer networks and decentralized platforms may offer us a glimmer of freedom, but without mass adoption, scalability, and seamless user experience, they remain niche alternatives.

This creates a paradox: the tools that could allow individuals to reclaim their autonomy are often too difficult or inaccessible for the average user. The notion of "sovereignty" in the digital world, much like its political counterpart, is one of constant negotiation. Governments are learning how to integrate blockchain technologies for more efficient control, while corporations leverage surveillance capitalism to expand their grasp on user behavior. Ironically, the very same technology that could empower individuals is becoming a tool for governance and control, albeit one that is harder to trace and combat. The question we need to grapple with is whether true decentralization is even achievable in a society so deeply embedded in corporate capitalism and surveillance mechanisms. At the same time, can we ever truly achieve the autonomy we crave, or will the future of digital space always be a game of tug-of-war, where the strings are pulled by invisible powers far beyond our control?

In a way, we are all participating in this grand experiment---sometimes as innovators, sometimes as victims---and our level of awareness determines how much influence we have over our own digital future. The question isn't just about how we can protect ourselves, but about whether we can transform the system from within. We may be able to opt-out of certain platforms, but as digital life becomes more entrenched, can we afford to truly escape the architecture that shapes us? The choices we make today in how we interact with technology will set the precedent for how future generations experience their own agency and sovereignty in an increasingly connected, monitored, and data-driven world.

This is all I have for today. I think this post is already very long (and much longer than I have initially intended for it to be), but I'd love to dive deeper into something else that's been on my mind recently: the global reliance on CDNs like Cloudflare. It's wild when you think about how much of the internet today is essentially built on the backs of these centralized systems. Cloudflare and similar services are everywhere, speeding up websites, making them "more secure," and keeping them online. The catch? As we depend more on them, we're putting a lot of trust in a handful of companies that control a massive portion of the web's infrastructure. This brings up some huge questions about power and control. What happens when a company like Cloudflare decides to pull the plug on a website---or worse, if it's compromised in a way that takes down whole sections of the internet? It's one thing to have content spread across servers worldwide, but it's another when those servers are owned by a handful of corporations. It creates single points of failure and makes the internet feel more like a corporate-controlled ecosystem rather than a decentralized space for free expression. There's also the reality that these services often make the calls about what's acceptable or not, sometimes with little transparency or accountability. We've seen this with Cloudflare's past deplatforming decisions, 5 which leave us asking, "Who gets to decide who stays online and who doesn't?"

Sorry, I'm rambling again. I hope I was able to pique your interest today and perhaps offer a different perspective. There are many interesting subtopics I could cover, but I would like to avoid overwhelming you with a wave of unfiltered thoughts. Special thanks to @mraureliusr for the initial proofreading, and of course, thank you for reading this. Cheers!

Footnotes

-

Perhaps an inconsequential one. How many of us care about the consequences of our data being shared freely? ↩

-

Bad example, I admit. Self-hosting e-mail servers is notoriously annoying, but this artificial difficulty is also a testament to the problem at hand. Why must hosting something as simple as e-mail be this difficult? Why will spam-lists immediately put you on their blocklist? Can we not have better solutions? Why does most of our technology suck? ↩

-

Years ago, a friend of mine shared a theory with me about humanity's tendency to cluster together. He argued that shared interests, appearances, or ideas naturally bring us together. According to him, this drive leads people to form groups that reinforce these commonalities. Over time, these groups become more insular, focused on mutual validation and a narrower set of values. Looking back, his theory seems particularly evident in tech communities. These spaces form around shared goals or ideologies, often growing into large instances where members develop a sense of identity and belonging. Yet, as these groups grow, they can transform into echo chambers--spaces where the same ideas are constantly amplified. Eventually, these communities may "defederate," or be "defederate_d_", through either external pressure or internal fracture, reinforcing their separation from broader networks in an effort to preserve their core beliefs. ↩

-

I will avoid picking the low hanging fruit that is Matrix and its clients. Make whatever you will from this footnote. ↩

-

Cloudflare has made notable deplatforming decisions that have sparked debates about free speech, censorship, and the power of private companies over the internet. One significant incident occurred in 2017 when Cloudflare terminated its services to The Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website. This decision followed the site's claims that Cloudflare secretly supported their ideology, prompting Cloudflare's CEO, Matthew Prince, to take action. In 2019, Cloudflare ceased services to 8chan, an imageboard linked to multiple mass shootings, including the tragic event in El Paso, Texas. Prince described 8chan as a "cesspool of hate" and cited its role in inspiring tragic events as the reason for the decision. ↩