Much of the confusion in the debate over whether social media1 is harming young people can be cleared away by distinguishing two different questions, only one of which needs an urgent answer:

The historical trends question: Was the spread of social media in the early 2010s (as smartphones were widely adopted) a major contributing cause of the big increases in adolescent depression, anxiety, and self-harm that began in the U.S. and many other Western countries soon afterward?

The product safety question: Is social media safe today for children and adolescents? When used in the ordinary way (which is now five hours a day), does this consumer product expose young people to unreasonable levels of risk and harm?

Social scientists are actively debating the historical trends question — we raised it in Chapter 1 of The Anxious Generation — but that’s not the one that matters to parents and legislators. They face decisions today and they need an answer to the product safety question. They want to know if social media is a reasonably safe consumer product, or if they should keep their kids (or all kids) away from it until they reach a certain age (as Australia is doing).

Social scientists have been debating this question intensively since 2017. That’s when Jean Twenge suggested an answer to both questions in her provocative article in The Atlantic: “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” In it, she showed a historical correlation: adolescent behavior changed and their mental health collapsed just at the point in time when they traded in their flip phones for smartphones with always-available social media. She also showed a correlation relevant to the product safety question: The kids who spend the most time on screens (especially for social media) are the ones with the worst mental health. She concluded that “it’s not an exaggeration to describe iGen [Gen Z] as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. Much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones.”

Twenge’s work was met with strong criticism from some social scientists whose main objection was that correlation does not prove causation (for both the historical correlation, and the product safety correlation). The fact that heavy users of social media are more depressed than light users doesn’t prove that social media caused the depression. Perhaps depressed people are more lonely, so they rely on Instagram more for social contact? Or perhaps there’s some third variable (such as neglectful parenting) that causes both?

Since 2017, that argument has been made by nearly all researchers who are dismissive about the harms of social media. Mark Zuckerberg used the argument himself in his 2024 testimony before the U.S. Senate. Under questioning by Senator Jon Osoff, he granted that the use of social media correlates with poor mental health but asserted that “there’s a difference between correlation and causation.”

In the last few years, however, a flood of new research has altered the landscape of the debate, in two ways. First, there is now a lot more work revealing a wide range of direct harms caused by social media that extends beyond mental health (e.g., cyberbullying, sextortion, and exposure to algorithmically amplified content promoting suicide, eating-disorders, and self-harm). These direct harms are not correlations; they are harms reported by millions of young people each year. Second, recent research — including experiments conducted by Meta itself — provides increasingly strong causal evidence linking heavy social media use to depression, anxiety, and other internalizing disorders. (We refer to these as indirect harms because they appear over time rather than right away).

Together, these findings allow us to answer the product safety question clearly: No, social media is not safe for children and adolescents. The evidence is abundant, varied, and damning. We have gathered it and organized it in two related projects which we invite you to read:

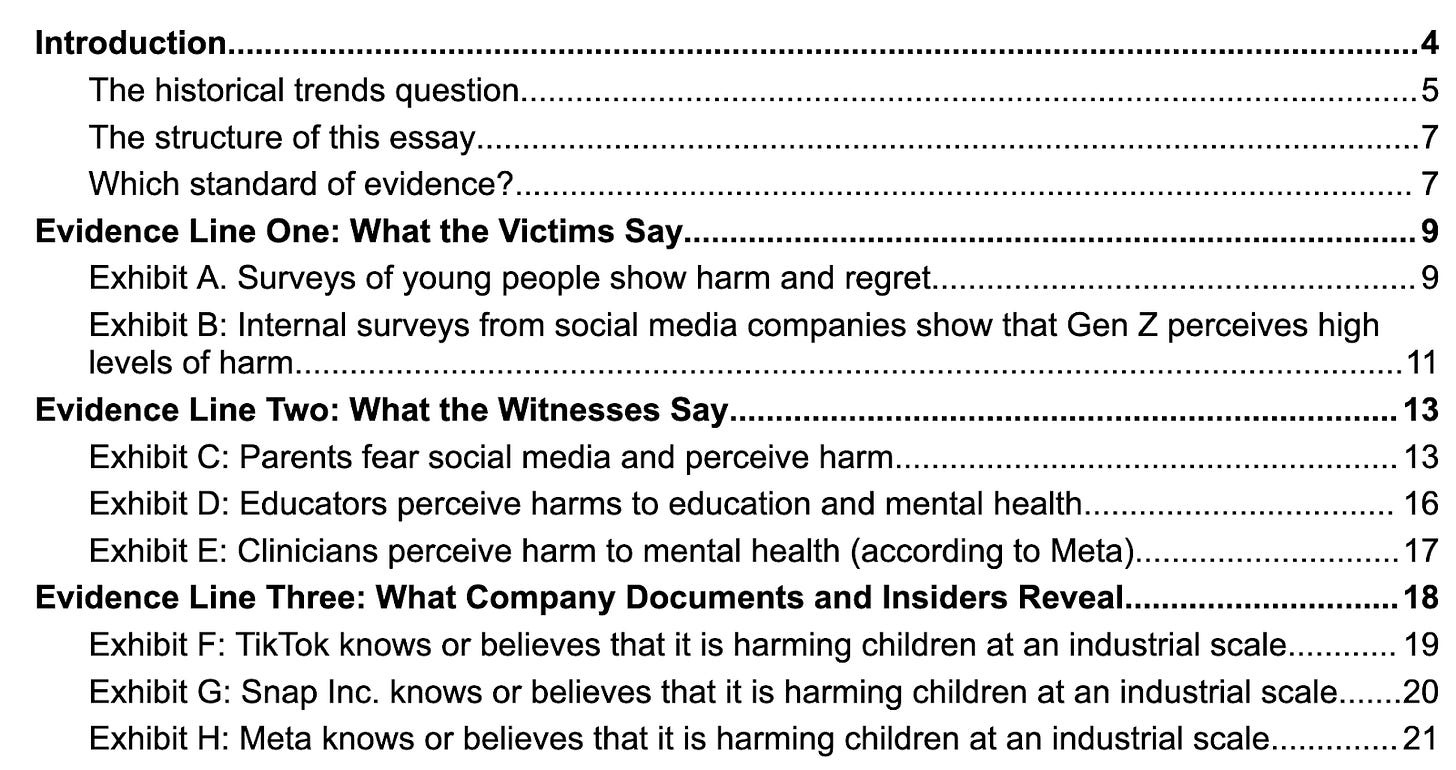

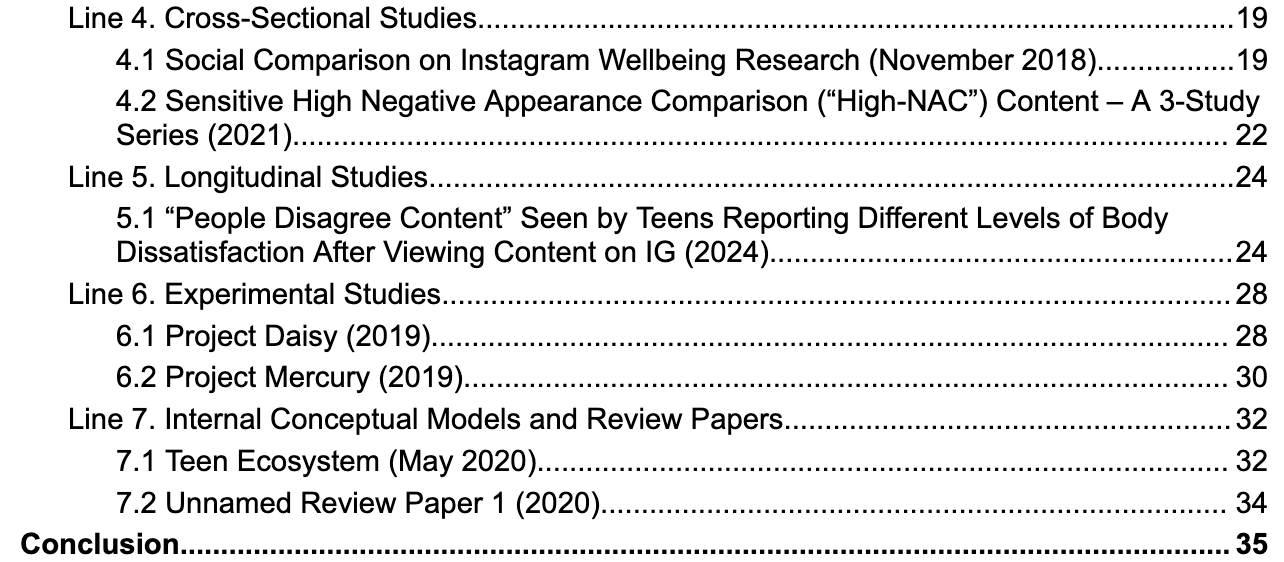

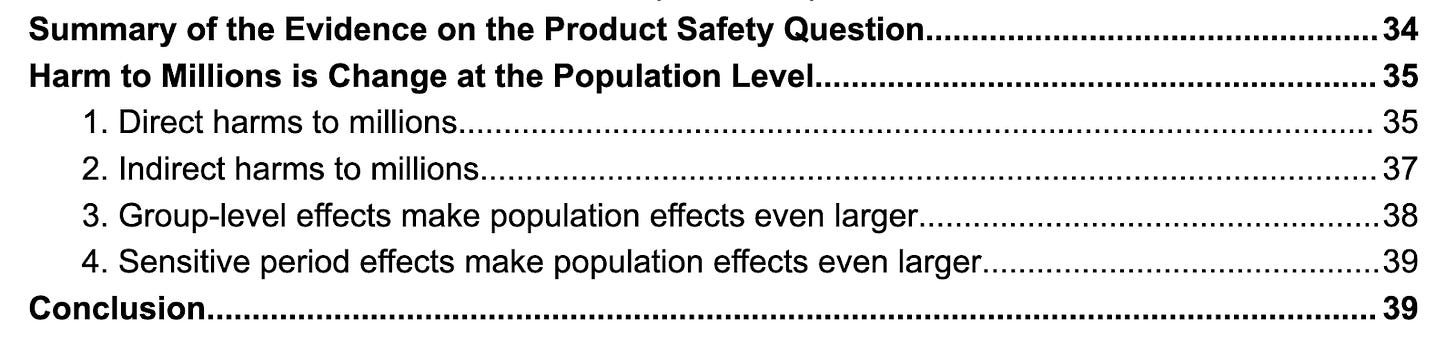

A review paper, in press as part of the World Happiness Report 2026, in which we treat the product safety question as a mock civil-court case and organize the available research into seven lines of evidence. The first three lines reveal widespread direct harm to adolescents around the world. Lines four through seven reveal compelling evidence that social media substantially increases the risk of anxiety and depression, and that reducing social media use leads to improvements in mental health. Taken together, these lines of evidence provide a firm answer to the product safety question.

MetasInternalResearch.org, a new website that catalogues 31 internal studies carried out by Meta Inc. The studies were leaked by whistleblowers or made public through litigation — despite Meta’s intentions to keep them hidden. The most incriminating among them: an experiment designed to establish causality, where Meta’s researchers concluded that social media causes harm to mental health.

In the rest of this post we present the Tables of Contents from these two projects, so that you can jump into the projects wherever you like and see for yourself the many kinds of research demonstrating harm to adolescents. After that, we return to the historical trends question to suggest an answer. We show that the scale of harm we found while answering the product safety question is so vast, affecting tens of millions of adolescents across many Western nations, that it suggests (though does not prove) that the global spread of social media in the early 2010s probably was a major contributor to the international decline of youth mental health in the following years. We suggested this in Chapter 1 of The Anxious Generation. The two mountains of evidence we present here make that suggestion even more plausible today.

The Review Paper: Seven Lines of Evidence

The World Happiness Report (WHR) is a UN-backed annual ranking that has become the global reference point for national well-being research. It draws on Gallup World Poll data from more than 150 countries. We were invited to write a chapter for the upcoming WHR on the 2026 theme: the association between social media and well-being. Following their 2024 report, which documented a widespread decline of well being among young people, this year they ask whether social media’s global spread in the 2010s was a major contributor to that decline. Our chapter, “Social Media is Harming Young People at a Scale Large Enough to Cause Changes at the Population Level,” offers an answer to the product safety question — no — and to the historical trends question — yes.

The editors graciously allowed us to post our peer-reviewed chapter online before the March 19 publication date so that discussion and debate on this topic can begin immediately.

We structured the chapter as if we were filing a legal brief offering 15 exhibits organized into seven separate lines of evidence. The first three lines are the equivalent of testimony from witnesses in a trial. If the people who had the clearest view of an event say that Person A punched Person B, that would count as evidence of Person A’s guilt. The evidence is not definitive — the witnesses could be mistaken or lying — but it is legitimate and relevant evidence. Here’s the structure of that part of the chapter:

After establishing that the most knowledgeable witnesses perceive harm from social media, we move on to the four major lines of academic research. While most researchers agree that correlational studies find statistically significant associations between social media use and measures of anxiety and depression, and that social media reduction experiments find some benefits for mental health, the debate centers on whether the effects are large enough to matter.2 We show that the experimental effects and risk elevations are larger than is often implied — in fact, they are as large as many public health effects that our society takes very seriously (such as the impact of child maltreatment on the prospective risk of depression.)3

Furthermore, we take a magnifying glass to some widely cited studies that claim to show only trivial associations or effects between social media use and harm to adolescents (e.g., Hancock et al. (2022) and Ferguson (2024). We show that these studies actually reveal much larger associations when the most theoretically central relationships are examined — for example, when you focus the analysis on heavy social media use (rather than blending together all digital tech) linked specifically to depression or anxiety (rather than blending together all well-being outcomes) for adolescent girls (rather than blending in boys and adults).

Meta’s Internal Research: Seven More Lines of Evidence

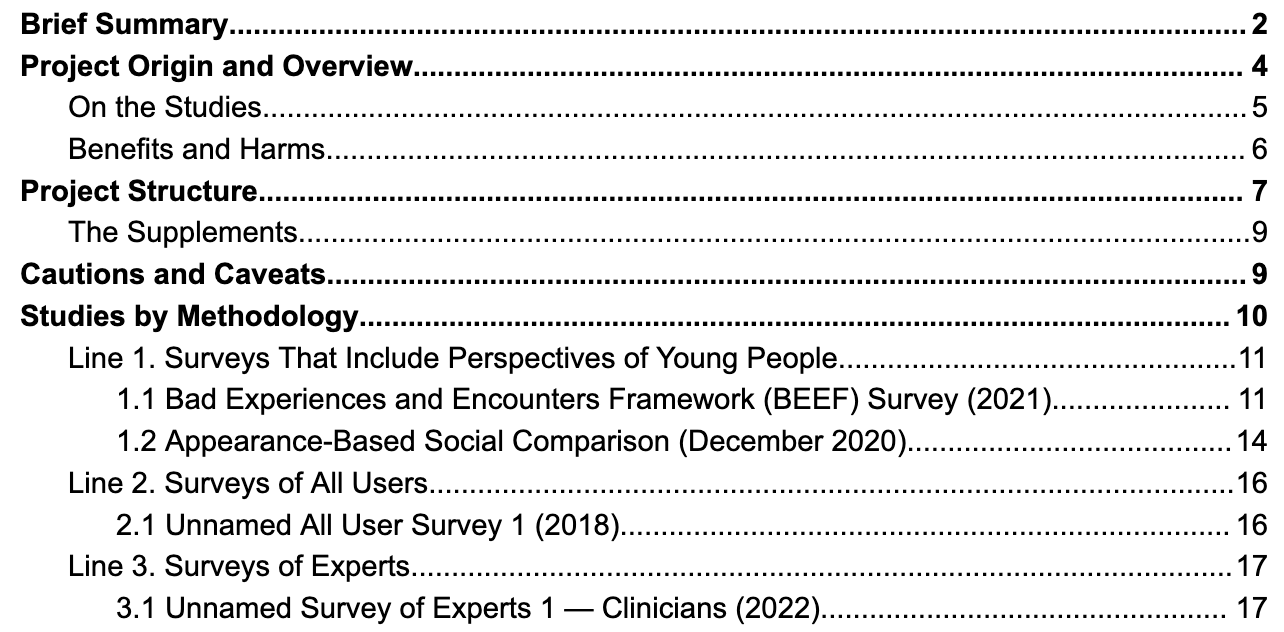

Throughout 2025, a variety of lawsuits against social media companies were progressing through the courts. In the briefs posted online by various state Attorneys General, we found references to dozens of studies that Meta had conducted. Some of this information had been available to the general public since 2021, when whistleblower Frances Haugen brought out thousands of screenshots of presentations and emails from her time working at Meta. Others were newly found by litigators in the process of discovery.4

The descriptions of these studies are scattered across multiple legal briefs, most of which are hundreds of pages long, so it has been difficult to keep track of them — until now. We have collected all publicly available information about the studies in one central repository, MetasInternalResearch.org. Indexed in this way, the scattered reports form a mountain of evidence that social media is not safe for children. The evidence was collected and hidden by Meta itself.

We found information on 31 studies related to the product safety question that Meta conducted between 2018 and 2024. Meta has long hired PhD researchers, particularly psychologists, to conduct internal research projects. (In January 2020, Jon met with members of this team and shared his concerns about what Instagram was doing to girls.) Meta’s researchers have access to vast troves of data on billions of users, including what exactly users saw and what emotions or behaviors they showed afterward. (This is known as “user-behavioral log data.”) Academic researchers never get access to rich data like this; they must devise their own surveys, which obtain a few crude proxy variables (such as “how many hours a day do you spend on social media?” and “How anxious were you yesterday?”). So we should pay attention to what Meta’s researchers found and how they interpreted their findings.

In one example, recently unsealed court documents from lawsuits brought by U.S. school districts against Meta and other platforms reveal that Meta conducted its own randomized control trial (considered to be the best way to study causal impact) in 2019 with the marketing research firm Nielsen. The project — code-named Project Mercury — asked a group of users to deactivate their Facebook and Instagram accounts for one month. According to the filings, Meta described the design of their study as being “of much higher quality” than the existing literature and that this study was “one of our first causal approaches to understand the impact that Facebook has on people’s lives… Everyone involved in the project has a PhD.” In pilot tests of the study, researchers found that “people who stopped using Facebook for a week reported lower feelings of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and social comparison.” One Meta researcher also stated that “the Nielsen study does show causal impact on social comparison.”

In other words, Meta’s own research on the effects of social media reduction confirms those from academic researchers that we report in Line 6 of our review paper. Both sets of researchers find evidence of causation, not mere correlation.

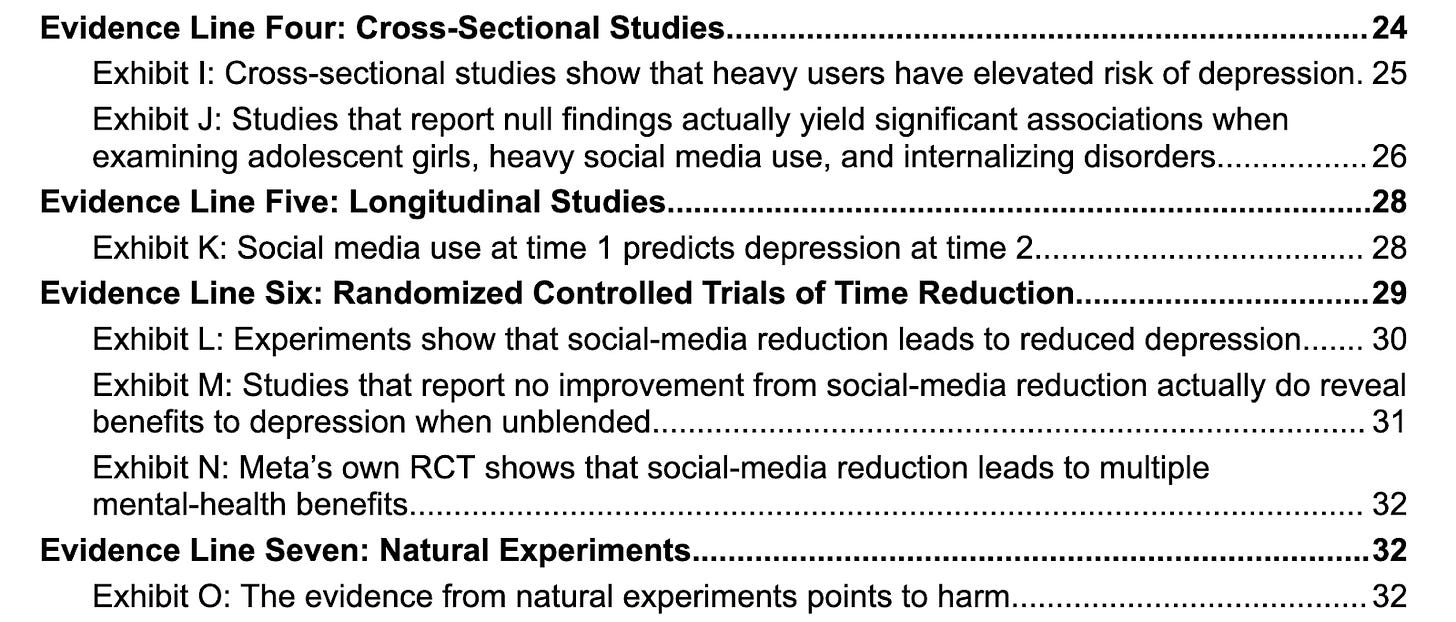

We were impressed by the great variety of methods that Meta’s researchers used. In fact, the 31 studies we located fit neatly into seven lines that are similar to the seven lines we used in our review paper. The findings from Meta researchers are highly consistent with the findings from academic researchers, which gives us even more confidence in our conclusions about the product safety question.

Here’s the Table of Contents. Once again, after the introductory material, we present three lines of testimony:

We then move on to lines 4, 5, and 6, which correspond exactly to lines 4, 5, and 6 in the review paper: correlational, longitudinal, and experimental studies, although line 7 is unique. (It involves reviews of academic literature conducted by Meta’s researchers.)

Returning to the Historical Trends Question

The product safety question is distinct from the historical trends question. A consumer product (e.g., a toy or food) can be unsafe for children without it producing an immediate or easily detectable increase in national rates of a particular illness.5

But social media is an unusual consumer product because of its vast user base and the enormous amount of time it takes from most users. It’s as if a new candy bar, intentionally designed to be addictive, was introduced in 2012 and, within a few years, 90% of the world’s children were consuming ten of these candy bars each day, which reduced their consumption of all other foods. Might there be increases in national rates of adolescent obesity and diabetes?

In our WHR review paper, we estimate the scale of direct harms (e.g., cyberbullying, sextortion, and exposure to disturbing content) and indirect harms (e.g., elevated risks of depression, anxiety, and eating disorders). We then show that these estimates are likely underestimates because they don’t account for network effects inherent to social media, nor the heightened impact of heavy use during the sensitive developmental period of puberty. All told, the number of affected children and adolescents likely reaches into the hundreds of millions, globally.

Once we consider the vast scale at which social media operates — used by the large majority of young people, for many hours each day, over many years, and across nearly all Western nations — it becomes clear that social media companies are harming young people on an industrial scale. It becomes far more plausible that this consumer product caused national levels of adolescent depression and anxiety to rise, especially for girls.

Conclusion: What Now?

Academic debates over media effects often take decades to resolve. We expect that this one will continue for many years. But parents and policymakers cannot wait for resolution; they must make decisions now, based on the available evidence. The evidence we have collected shows clearly that social media is not safe for adolescents.

We believe that the evidence of direct and indirect harm that we have collected in these two complementary projects is now sufficient to justify the sort of action that the Australian government took in 2025 when it raised the age for opening or maintaining a social media account to 16. Just as the recent international trend of removing smartphones from schools is beginning to produce educational benefits, the research we reviewed suggests that removing social media from childhood and early adolescence is likely to produce a great variety of benefits, including lower rates of depression and many fewer victims of direct harms such as sexual harassment and sextortion.

Countries around the world ran a giant uncontrolled experiment on their own children in the 2010s by giving them smartphones and social media accounts at young ages. The evidence is in: the experiment has harmed them. It is time to call it off.

By “social media” we mean platforms that include user profiles, user-generated content, networking, interactivity, and (in most cases) algorithmically curated content. Platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube, Reddit, and X all share these features. This means that ordinary use includes interacting with adult strangers.

For examples of studies showing substantial risk elevations, see Kelly et al. (2019), Riehm (2019), Twenge et al. (2022), and Grund (2025). For examples of meaningful experimental effects, see Burnell et al. (2025).

Burnell et al. (2025) report an average effect of roughly g = 0.22 (about one-fifth of a standard deviation) for “well-being” outcomes in sustained social-media-reduction studies. Grummitt et al. (2024) estimate that the increased risk of depression and anxiety attributable to childhood maltreatment corresponds to effects of d = 0.22 and d = 0.25, respectively. See section “Indirect Harms to Millions” for more details.

We note that this is our only source of this information because Meta lobbies against legislation that requires them to share data with researchers, such as the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act.

The trend of any particular harm may of course have several major influences, some of which may counteract each other. This can add considerable complexity to the historical trends question.