When the Human Genome Project (HGP) released its initial draft sequence in 2001, President Bill Clinton hailed it as “the most wondrous map ever produced by mankind.” After more than ten years of work, an estimated $3 billion in research costs, and a “genome war” with Craig Venter’s private company, Celera Genomics, the project had produced a nearly complete sequence of a human genome.1

UK Prime Minister Tony Blair predicted that this map would yield “a revolution in medical science whose implications far surpass even the discovery of antibiotics.” (Whether this claim turned out to be true is debatable.) A few months later, the two teams — from HGP and Celera — published cover stories in Nature and Science, respectively.

Although the quest to sequence a human genome began in 1990, the techniques it used had already been in development for more than twenty years. And those DNA sequencing methods, in turn, were directly inspired by protein and RNA sequencing research stretching all the way back to the 1940s.

In the twenty years after the draft human genome was first released, the average sequencing cost per genome fell roughly one hundred thousand-fold, ending up just north of $500. In that same period, the cost to sequence a million letters or “megabase” of DNA fell to six tenths of a cent.2 This plummeting price is due largely to technological innovation, including new sequencing chemistries, computational methods for assembling raw reads into finished genomes, and highly efficient commercial sequencing machines.

Out of the many sequencing methods developed over the decades, five are particularly important. These are their histories.

Sanger Sequencing

Fred Sanger was biology’s great decoder. A British biochemist who spent his entire career at the University of Cambridge, Sanger earned two Nobel Prizes in the same field: first, the 1958 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for creating a method to determine the amino acid sequence of proteins (most famously insulin) and, second, a share of the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for inventing methods to sequence DNA.

After winning his first Nobel, Sanger turned his gaze to RNA, seeking to become the first person to sequence a full strand. He was beaten by Cornell biochemist Robert Holley, however, who reported the full 77-nucleotide sequence of the alanine transfer RNA molecule in 1965.3

Although many scientists today assume that Sanger was the first to figure out how to sequence DNA, that’s not the case. As with RNA, Sanger was edged out by a Cornell biochemist. This time it was Ray Wu, who, in 1970, published a method to “read” specific sections of two bacterial virus genomes, called λ and bacteriophage 186. Wu’s method was only capable of sequencing “cohesive ends,” short single-stranded sections of these particular phage genomes, and so wasn’t considered a “general” solution to the DNA sequencing problem. In 1974, Wu’s lab refined this technique into the first general sequencing method, but it proved extremely labor-intensive and failed to catch on.

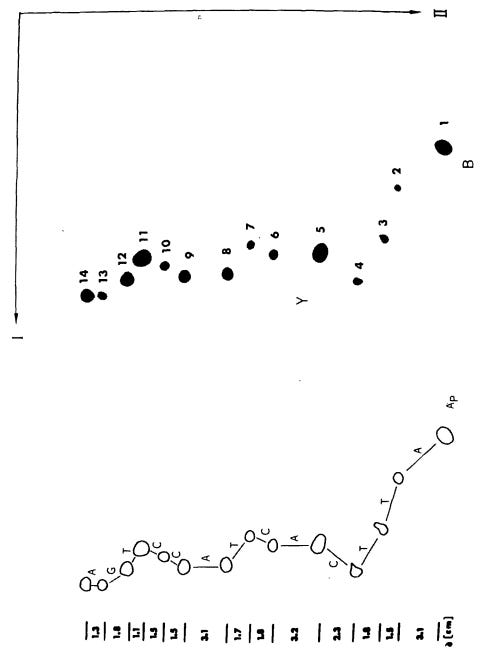

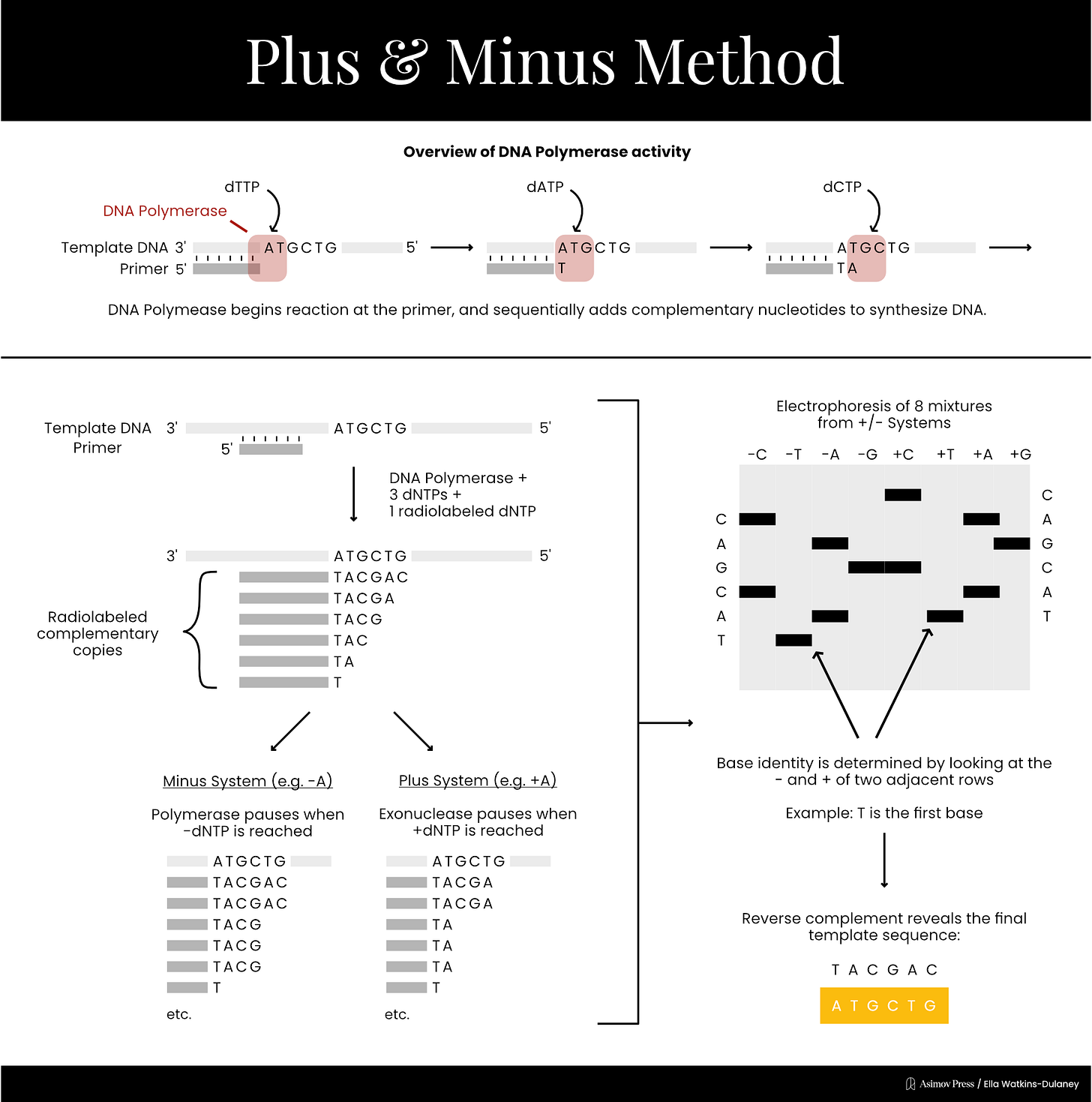

In 1975, Sanger published his own DNA sequencing method alongside laboratory technician Alan Coulson, called the “plus and minus” technique. First, scientists mixed the DNA strand to be sequenced with an enzyme, DNA polymerase, as well as a primer, three normal dNTPs and one radiolabeled dNTP. Radiolabeled nucleotides are incorporated into growing DNA strands just like normal nucleotides, but are tagged with radioactive isotopes, such as phosphorus-32 or sulfur-35, so they can be detected using radiation-measuring equipment.

This reaction would contain only low concentrations of the dNTPs and relied upon brief incubation times, so that DNA synthesis would stall at random positions along the template and yield a population of DNA fragments with varying lengths. These unfinished DNA fragments were then purified and used as templates in four “minus” and four “plus” reactions.

For each minus reaction, the purified DNA fragments were incubated together with three of the four dNTPs, meaning each fragment would be extended by DNA polymerase until the missing nucleotide was needed, at which point synthesis would halt.

Plus reactions worked differently: they used T4 DNA polymerase, an enzyme with strong 3’ to 5’ exonuclease activity, meaning it can chew back the end of a DNA strand. In the presence of only one dNTP, T4 DNA polymerase would degrade each fragment from its 3’ end until it reached a nucleotide complementary to that dNTP, at which point the exonuclease activity would be inhibited. This ensured that all fragments in a given plus reaction ended with the same nucleotide.

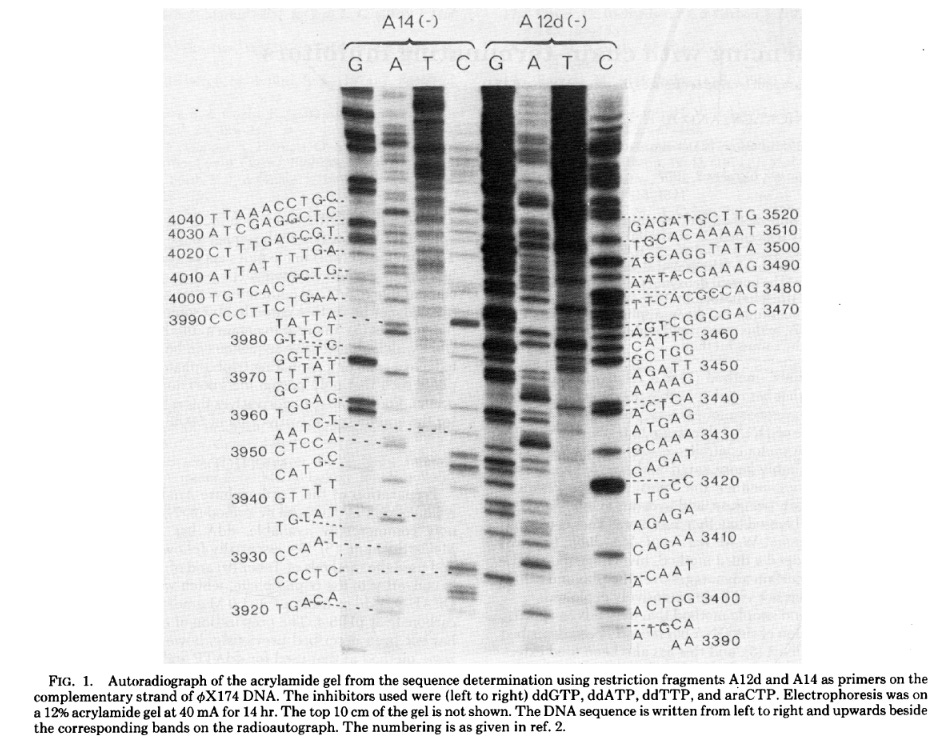

Since the eight reactions were run on fragments of random length, the eight plus and minus reactions collectively produced DNA fragments of all possible lengths.4 The fragments in these eight reactions were separated by size (using gel electrophoresis) and then imaged with autoradiography. Gels were dried and then placed against X-ray film, allowing the radioactive DNA fragments to expose the film and appear as dark bands, which a scientist could then painstakingly translate into the DNA sequence. In 1977, Sanger and colleagues sequenced the first full DNA genome using this method: a small bacterial virus with 5,386 nucleotides in its genome, called ɸX174 or “PhiX.”

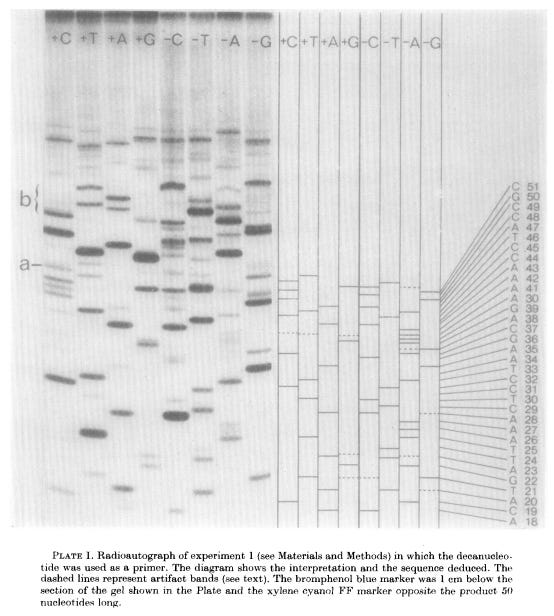

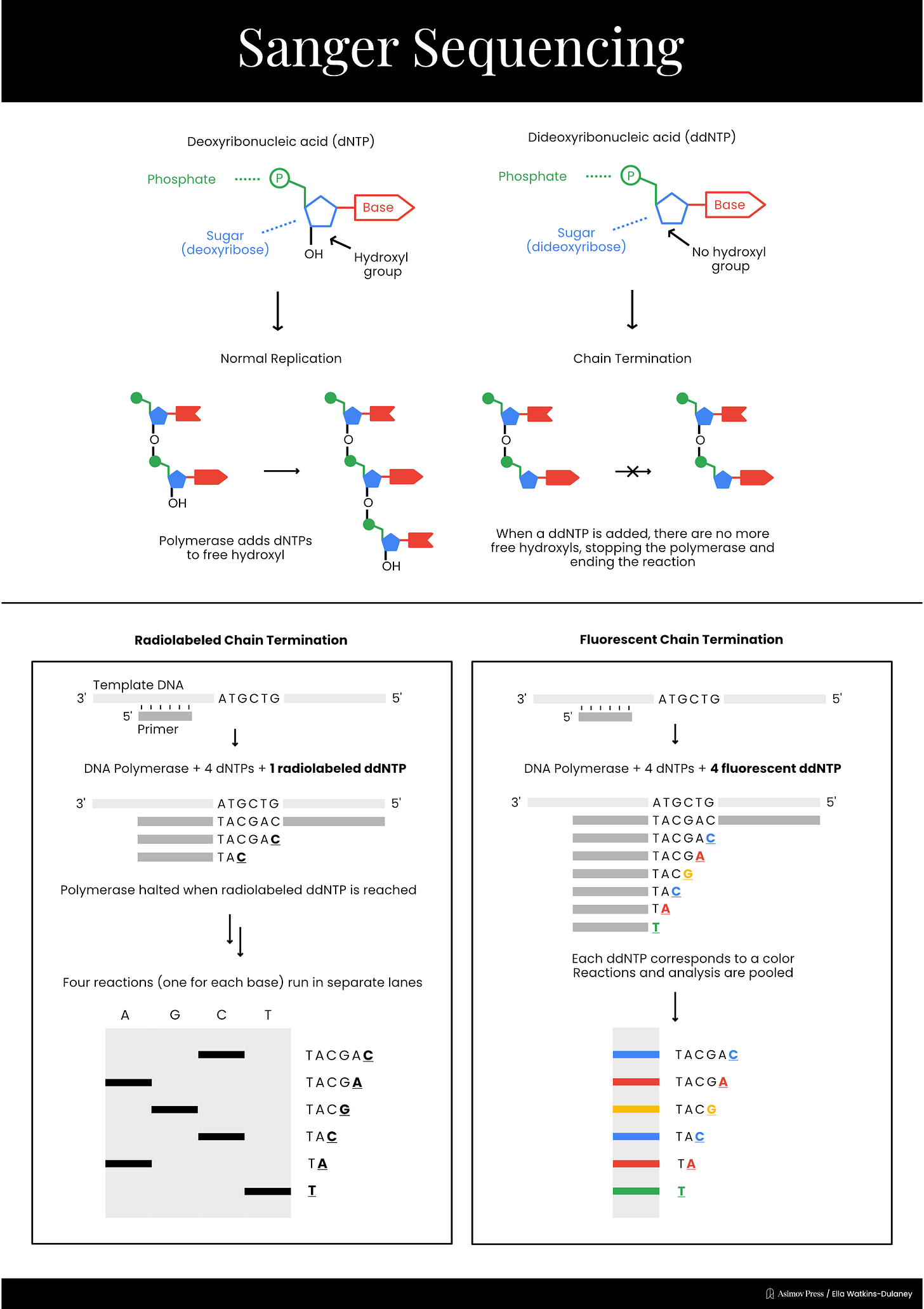

In 1977, Sanger developed a much simpler sequencing method, called “chain termination,” which is today known simply as Sanger sequencing. This technique took advantage of a different type of special nucleotide called a dideoxyribonucleotide, or ddNTP. ddNTPs lack one of the hydroxyl groups present on a normal dNTP, preventing the chemical reaction necessary to add another nucleotide and terminating DNA elongation.

Sanger sequencing reaction mixtures included purified template DNA, a primer, DNA polymerase, and all four dNTPs. Each reaction also included a radiolabeled ddNTP version of just one of the four nucleotides. Only a small amount of each ddNTP was added, however, to ensure that a fraction of the total DNA fragments produced stopped at each occurrence of that base. As with previous methods, separating fragments via length and performing autoradiography allowed scientists to read the final sequence.

A different sequencing method that chemically cleaved DNA at specific bases, developed by Allan Maxam and Walter Gilbert, was the dominant technology into the 1980s. Radiolabeled DNA samples were incubated in four separate reactions, each of which contained a chemical that cleaved after a different nucleotide — either A/G, G, C, or C/T. By adding the right amount of each chemical, it was possible to produce different fragments chopped off at each individual base. The sequence could then be read using gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Maxam–Gilbert sequencing was easier than the plus and minus method to run and interpret, but was eventually surpassed by Sanger’s chain termination method, which molecular biologists found both technically preferable and more “elegant” since it mirrored the natural copying of DNA.

While Sanger sequencing was highly accurate and less labor-intensive than its predecessors, it still required the use of radioactive reagents and manual sequence recording. In 1986, Leroy Hood’s lab at Caltech replaced the radiolabeled ddNTPs with fluorescently labeled nucleotides, using fluorophores that emitted different colors of light for each base. They were now able to run the products of all four reactions on the same gel and have a computer read the sequence by detecting the color of each fluorescent signal as fragments passed through a laser beam.

The first commercial Sanger sequencing machine was produced that year by Applied Biosystems (ABS), which Hood had co-founded in 1981. Called the ABI 370A, it retailed for $92,500. Since Sanger never patented his method, other companies were free to develop competing products, and by 1988, there were three Sanger sequencing machines on the market. These were followed by numerous others, including the Perkin-Ellmer 3700, used by Celera and the Human Genome Project, and the ABS 3500 Genetic Analyzer, which is still found in many laboratories today.

454 Pyrosequencing

By the time Sanger sequencing was commercialized, the groundwork for an entirely new sequencing chemistry was already well underway. In 1985, Swedish biochemists Pål Nyren and Arne Lundin published a paper illustrating a procedure that measured the concentration of a molecule, called pyrophosphate (PPi), using an enzymatic cascade that emits light. In early 1986, Nyren realized that the method he’d helped develop could be applied to DNA sequencing, because PPi is naturally produced as a byproduct of DNA synthesis.5

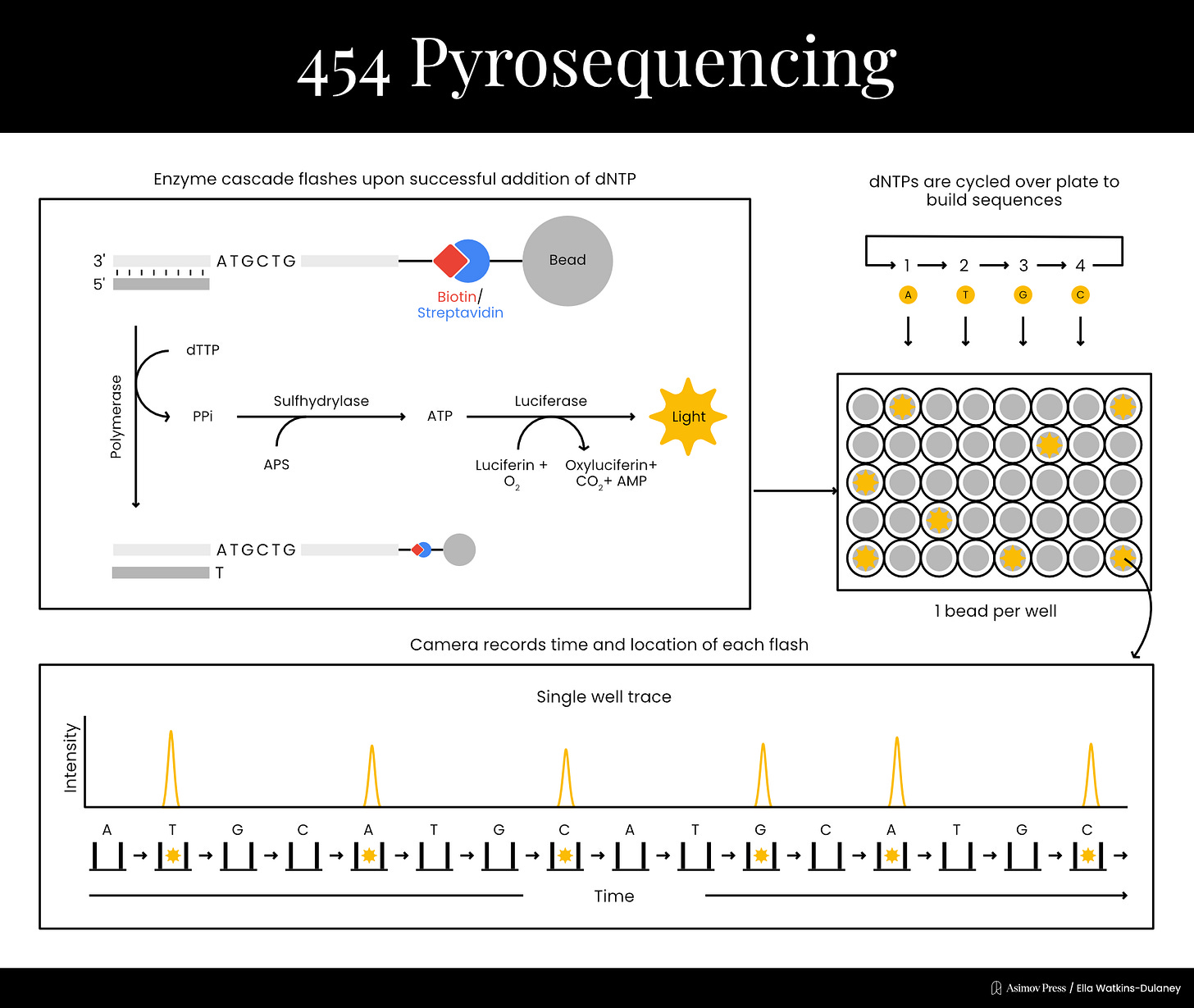

Funding limitations prevented Nyren from dedicating much time to the project at first, but in 1993, he was finally able to publish a proof-of-principle. His technique began by mixing the template DNA with a primer, a single dNTP, and three enzymes: the familiar DNA polymerase plus the light cascade enzymes, ATP sulfurylase and firefly luciferase.6 If the dNTP was incorporated into a strand of DNA, PPi would be produced in the chemical reaction. ATP sulfurylase could then convert the PPi into ATP, which would provide energy for the luciferase enzyme, producing light. Thus, it was possible to determine each base in the sequence by cycling through the dNTPs one at a time until light was detected, and then washing extra nucleotides out between each step. By literally rinsing and repeating, the sequence could be recorded one letter at a time without the use of any gels, which often took hours to run and were difficult to automate.

Nyren’s sequencing method earned the name “pyrosequencing” since it revolved around the production of pyrophosphate. At first, pyrosequencing could sequence only short DNA snippets, with a few nucleotides. In 1996, however, Nyren’s lab demonstrated sequencing of up to 15 bases by using a modified “A” nucleotide to reduce their signal-to-noise ratio.7 In 1998, they increased this to 34 bases by adding another enzyme, called apyrase, to the mix; apyrase degraded unincorporated nucleotides, removing the need for constant wash steps.

The year before, Nyren’s lab had also spun off a company, Pyrosequencing AB, to refine and commercialize the technology. Pyrosequencing was not the firm that would bring the technology to market, however; that distinction went to Connecticut-based 454 Life Sciences, who licensed whole-genome pyrosequencing applications in 2003. 454 made chips which enabled highly efficient, parallelized sequencing reactions and released the GS20 sequencer in 2005 for the price of $500,000. The GS20 worked by attaching each individual DNA template molecule to a bead and copying it many times using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Each bead was then loaded into a well in a microplate, where sequencing reactions would be carried out. The light from luciferase activation could be detected through the bottom of the wells, enabling sequences to be read.

Pyrosequencing wasn’t developed early enough to be employed by the Human Genome Project or Celera, but it was still the first method other than Sanger sequencing to hit the commercial market, marking the start of “next generation” sequencing methods (NGS). Pyrosequencing worked in real-time, though it struggled to accurately capture regions with several of the same nucleotides in a row. This was because the amount of light didn’t always scale cleanly when pyrophosphate was produced through successive reactions.

In 2006, 454 collaborated with Swedish paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo to sequence the first million base pairs of the Neanderthal genome; the project would be completed four years later, albeit with some help from Illumina sequencing. Illumina and other subsequent NGS technologies rendered pyrosequencing non-competitive, and in 2013, 454 was shut down by Roche, which had acquired it six years earlier. The technology is still used today for some applications, but most importantly, it was the first commercially viable alternative to Sanger sequencing, and the first sequencing method that could be fully automated because it didn’t rely on gels or other tedious steps.

Sequencing by Synthesis

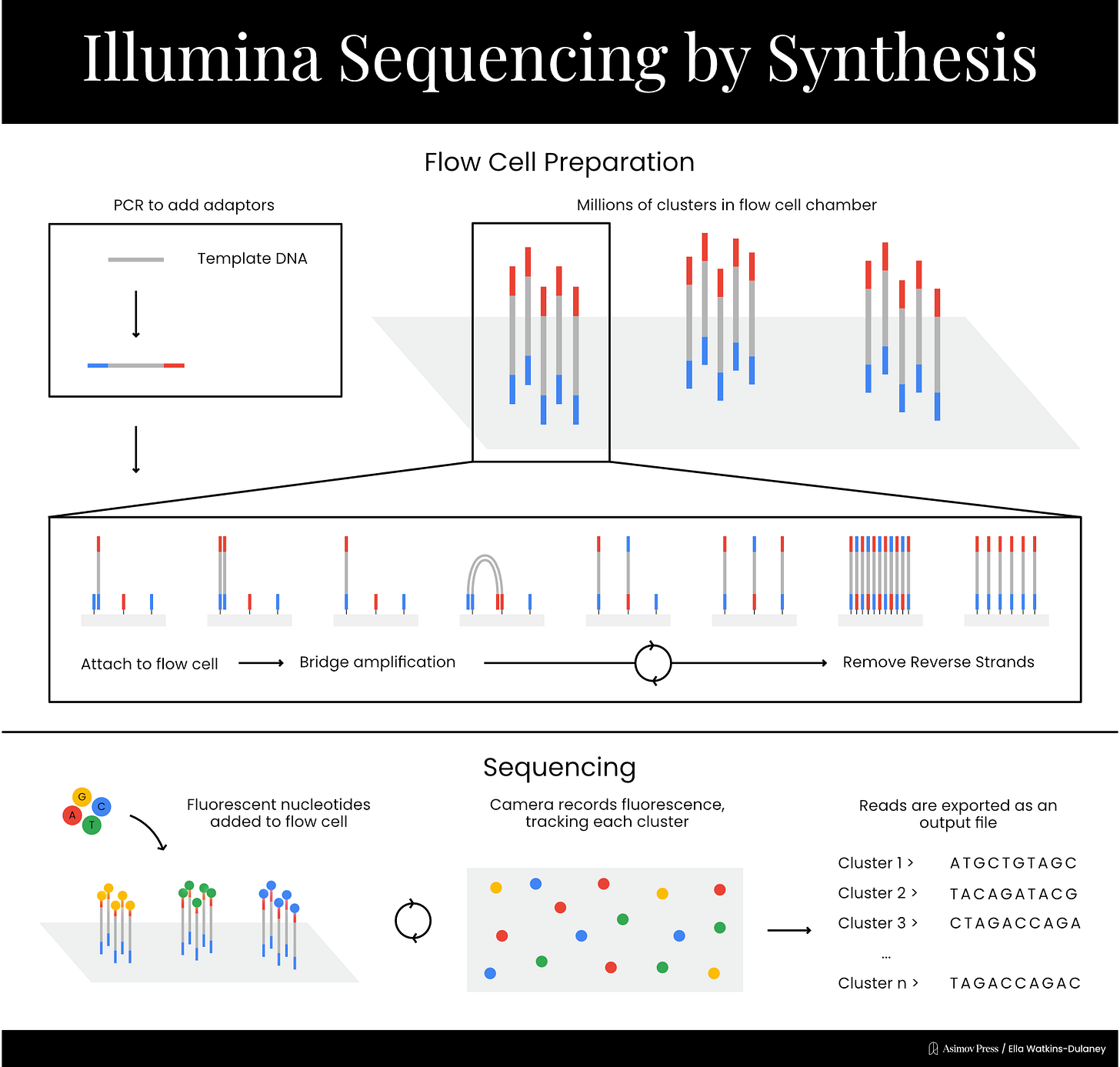

In the mid-1990s, University of Cambridge biochemists David Klenerman and Shankar Balasubramanian were trying to solve a fundamental problem: how to watch a single DNA polymerase molecule at work. Their approach used modified nucleotides, called reversible terminators, tagged with four different colors of fluorescent molecules. If one of these “terminators” was grabbed by the DNA polymerase and incorporated onto the replicating DNA strand, it would block the addition of any other bases until removed using a separate chemical reaction.

Klenerman and Balasubramanian’s great insight was that template DNA could be sequenced by synthesizing a complementary strand of reversible terminators; basically, extending the chain one base at a time and determining the identity of each nucleotide by looking at the color of its fluorophore. In 1998, the pair started a company called Solexa to develop the technology.

Detecting fluorescence from a single DNA molecule proved difficult in practice, however. And so, in 2004, Solexa acquired the IP rights to a method called colony sequencing, developed by French scientists Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli, to solve the detection problem. Colony sequencing affixed DNA fragments to a surface and amplified them over and over, generating “colonies” containing massive numbers of identical DNA strands. By reading the fluorescence from each strand in a colony simultaneously, it became possible to determine the base added at each step with much better accuracy, since random errors in individual strands would be averaged out by the consensus signal.

Now that single-molecule detection was no longer necessary, Solexa was able to develop its signature sequencing chemistry. The process takes place on a chip called a flow cell, which contains a lawn of short DNA sequences affixed to its surface. The template DNA is broken up into small fragments, and adapter sequences, complementary to the DNA on the flow cell’s surface, are added to the ends of each fragment. DNA fragments are then passed over the flow cell, where the adapter sequences bind to spots on the DNA lawn. At this point, primers are added, and an initial round of amplification takes place: the short DNA sequences on the flow cell are extended to create sequences complementary to the bound template DNA fragments, which are then washed away. The sequences present in the fragments of template DNA are now affixed directly to the flow cell.

At this point, each bound sequence exists as a single copy, which produces too faint a signal to detect reliably. Colony sequencing solves this by generating clusters of identical fragments through a process called bridge amplification. The adapter on the free end of each DNA strand will be complementary to some of the original, short sequences on the DNA lawn, and when this binding occurs, the strand bends over to form a bridge shape. Another round of amplification takes place, resulting in two complementary strands each directly affixed to the flow cell. This “bridge amplification” process is repeated over and over to propagate the sequence.

From here, the actual sequencing can begin. Primers and fluorescently-labeled chain terminators are added to the reaction mixture, resulting in the addition of one nucleotide to each strand of DNA on the lawn. A picture is taken of the entire chip, then the chain terminators’ blockers are cleaved to allow addition of the next base. This process proceeds until the reaction is complete, resulting in massively parallelized sequencing. The short reads acquired through this process can be combined via a computational technique called paired end analysis, which links reads by analyzing overlapping sections, to generate the whole sequence.

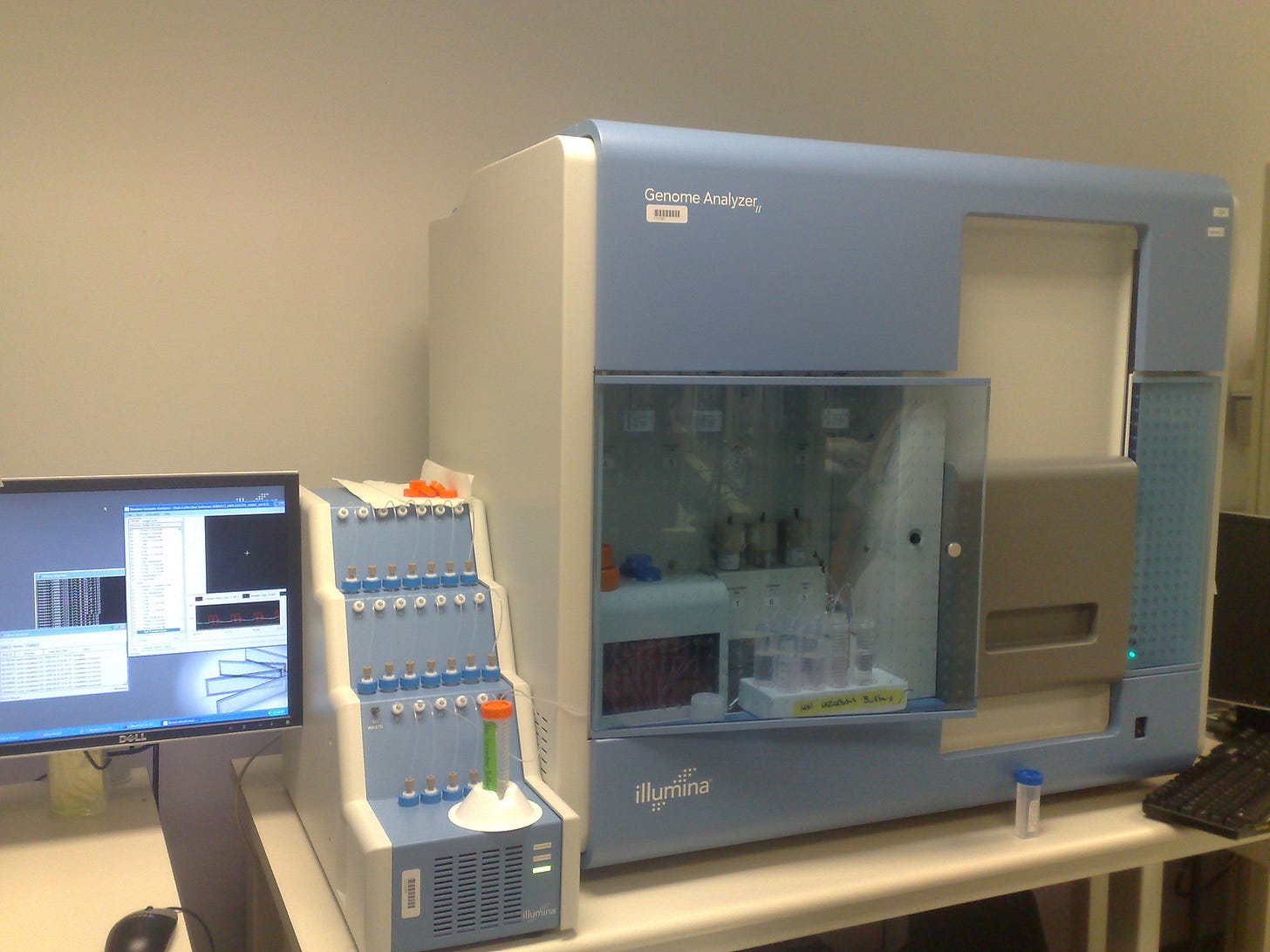

Solexa’s first product, the Genome Analyzer, launched in 2006 with a retail price of $400,000, and the company was acquired by the American genomics firm Illumina the following year. In 2008, the company published a paper demonstrating their technology’s ability to efficiently sequence whole genomes via short reads. Illumina’s method is commonly known as “sequencing by synthesis.” While the label could technically be applied to other methods, including Sanger’s, which also indirectly assesses sequence by detecting the incorporation of nucleotides complementary to the template strand, it’s most commonly used to refer to Illumina’s chemistry.

Since the release of Solexa’s Genome Analyzer, Illumina has created several new sequencing machines designed to fill different price niches. Illumina’s short reads are highly accurate, and the technique has played a crucial role in reducing average sequencing costs.

Unsurprisingly, Illumina has become by far the most common NGS method, maintaining roughly an 80 percent share over the last few years. This is largely owing to its versatility. Illumina sequencing has been used to create new reference genomes, including the common tomato, but has been especially useful in cases requiring repeated sequencing of short DNA sequences. For example, Illumina machines are routinely used to quantify the activity of genome editors like CRISPR; template DNA will either be edited or unedited, and reading the area around the edit many times provides an accurate quantification of editing percentages. Similarly, large numbers of short reads are useful for sequencing ancient DNA, taken from bones or other remains, since such samples often have degraded stretches. In addition to its role in the Neanderthal Genome Project, Illumina has been used to sequence 10,000-year-old human bodies and to track migration and population turnover in Neolithic Denmark.

PacBio SMRT Sequencing

While Illumina ultimately opted for a method that simultaneously detected massive numbers of DNA strands, others still believed that single-molecule sequencing methods offered a better path forward. Sequencing by synthesis requires repeated amplification, which introduces the possibility of error at each step and biases outputs towards sequences readily amplified by DNA polymerase. Single-molecule techniques were billed as a way to sequence DNA with minimal bias while simultaneously reducing cost.

The first such method was developed in biophysicist Steve Quake’s lab at Caltech and commercialized by Helicos Biosciences, but became unavailable after the company declared bankruptcy, saddled by legal issues and unable to find a market niche. These days, the canonical technique comes from a company called Pacific Biosciences (PacBio). Scientists often refer to single-molecule techniques as “third-generation” DNA sequencing, though they’re often also lumped into the NGS bucket with Illumina.

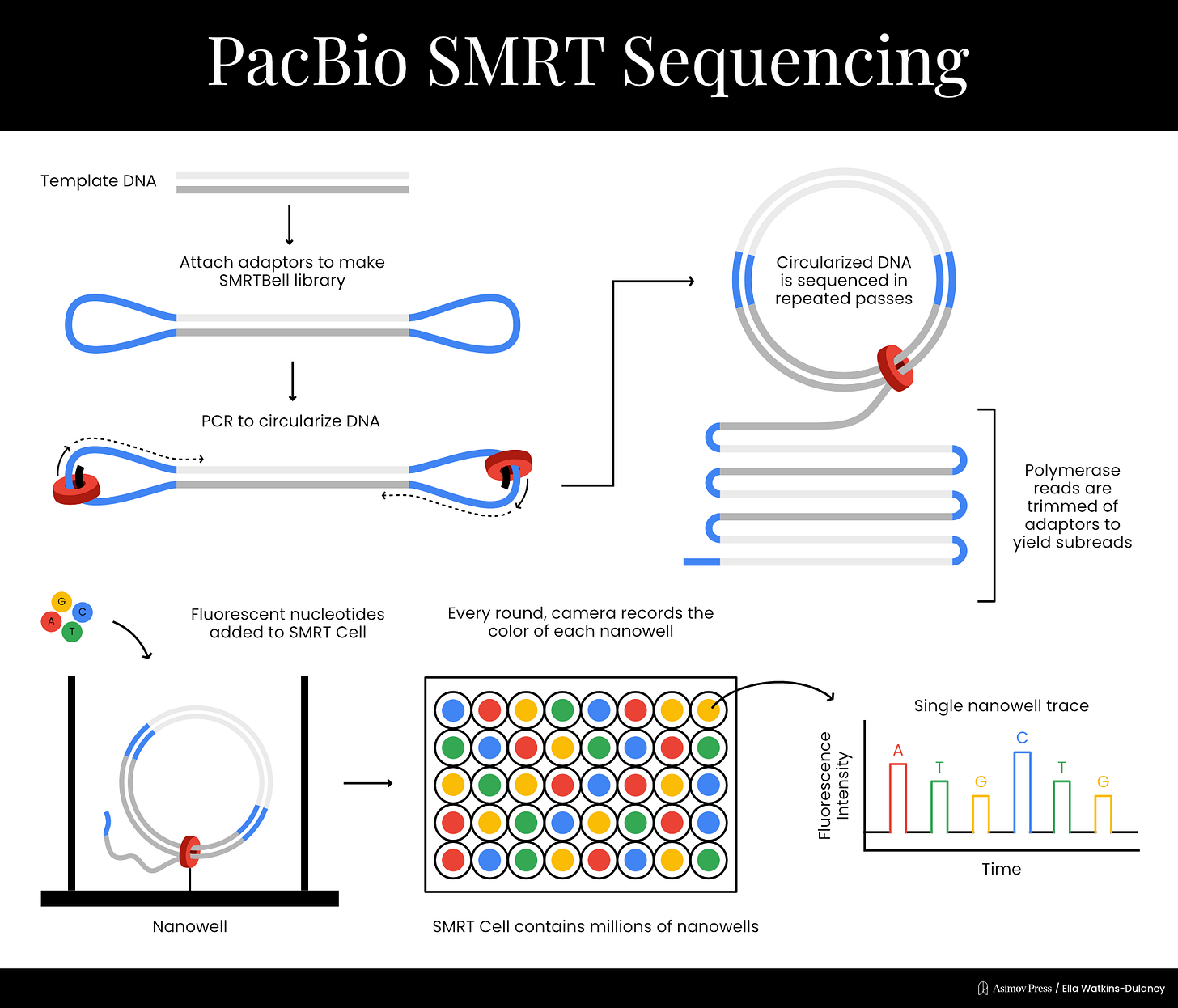

PacBio was founded in 2004 to develop sequencing methods based on work done in the labs of biophysicist Watt Webb and engineer Harold Craighead, both at Cornell University. The previous year, the two had collaborated to create zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs): small containers just big enough to hold a single DNA polymerase and containing tiny holes at the bottom through which light could be detected. They were able to fix a DNA polymerase to the bottom of a ZMW and detect the incorporation of individual fluorescent “C” nucleotides through the holes, which fed into a microscope capable of detecting light emissions.

In 2009, PacBio published a paper expanding the principle into a full-blown sequencing technique. Once again, each nucleotide was labeled with a different colored fluorophore detectable by the ZMW to determine which base had been incorporated. The fluorophores were attached such that they would be cleaved off during the chemical reaction incorporating the base into the growing DNA strand; they would then diffuse out of the ZMW so that the next fluorophore could be detected. Sequencing took place on a chip with many wells simultaneously — a different type of parallelization where each well detected a single DNA molecule undergoing the same basic chemical reaction.

The next year, PacBio developed a new method to allow multiple sequencing passes on the same DNA molecule. Double stranded DNA templates were ligated to two single stranded adapters, creating what the company called a “SMRTbell template.” Sequencing began at a primer on one of the adaptors and could proceed multiple times per molecule due to circularization, in a process called rolling-circle amplification. This helped reduce PacBio’s error rates significantly.

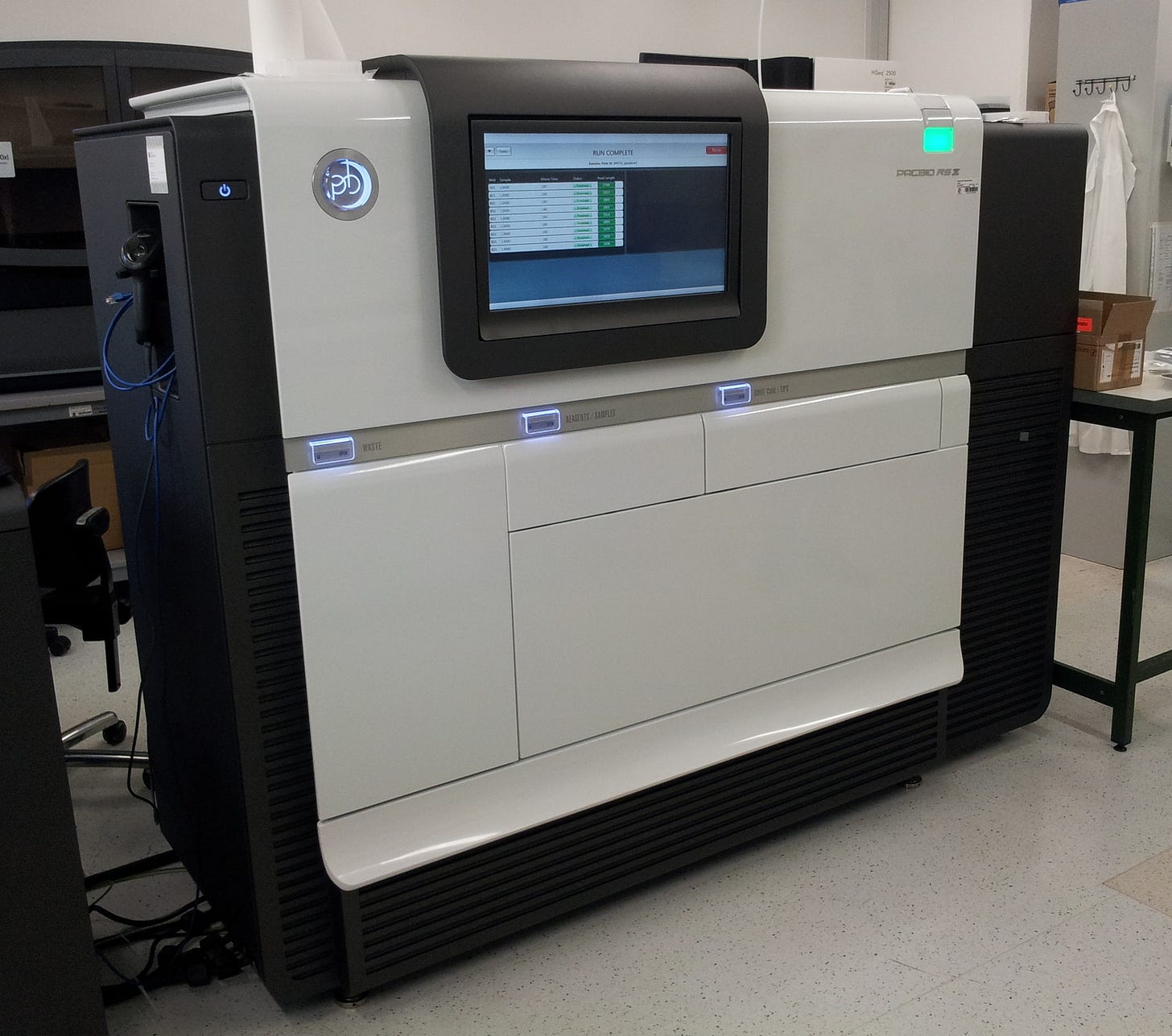

With its core technology in place, PacBio was ready to go commercial. In 2011, the company released the RS sequencing machine, and has since created multiple new machines containing chips with increased numbers of sequencing wells. PacBio calls the technique single molecule real time (SMRT) sequencing, though it’s colloquially referred to simply as PacBio sequencing. Rather than producing short overlapping reads like Illumina, PacBio generates very long reads; at first these were a few thousand bases, but today they can be well over 10,000.

PacBio’s ability to produce extremely long reads makes it a useful complement to Illumina. Indeed, PacBio machines are better at sequencing “confusing” genomes, such as those with many copies of the same gene, long stretches of repetitive motifs, and “structural variations” like large insertions or deletions, which may not show up in short-read sequences. For instance, PacBio was used to sequence a very difficult bacterium called Clostridium autoethanogenum, which contains repeats, nine copies of a single gene, and insertions from bacterial virus genomes — basically the genomic equivalent of a Thomas Pynchon novel.

Nanopore Sequencing

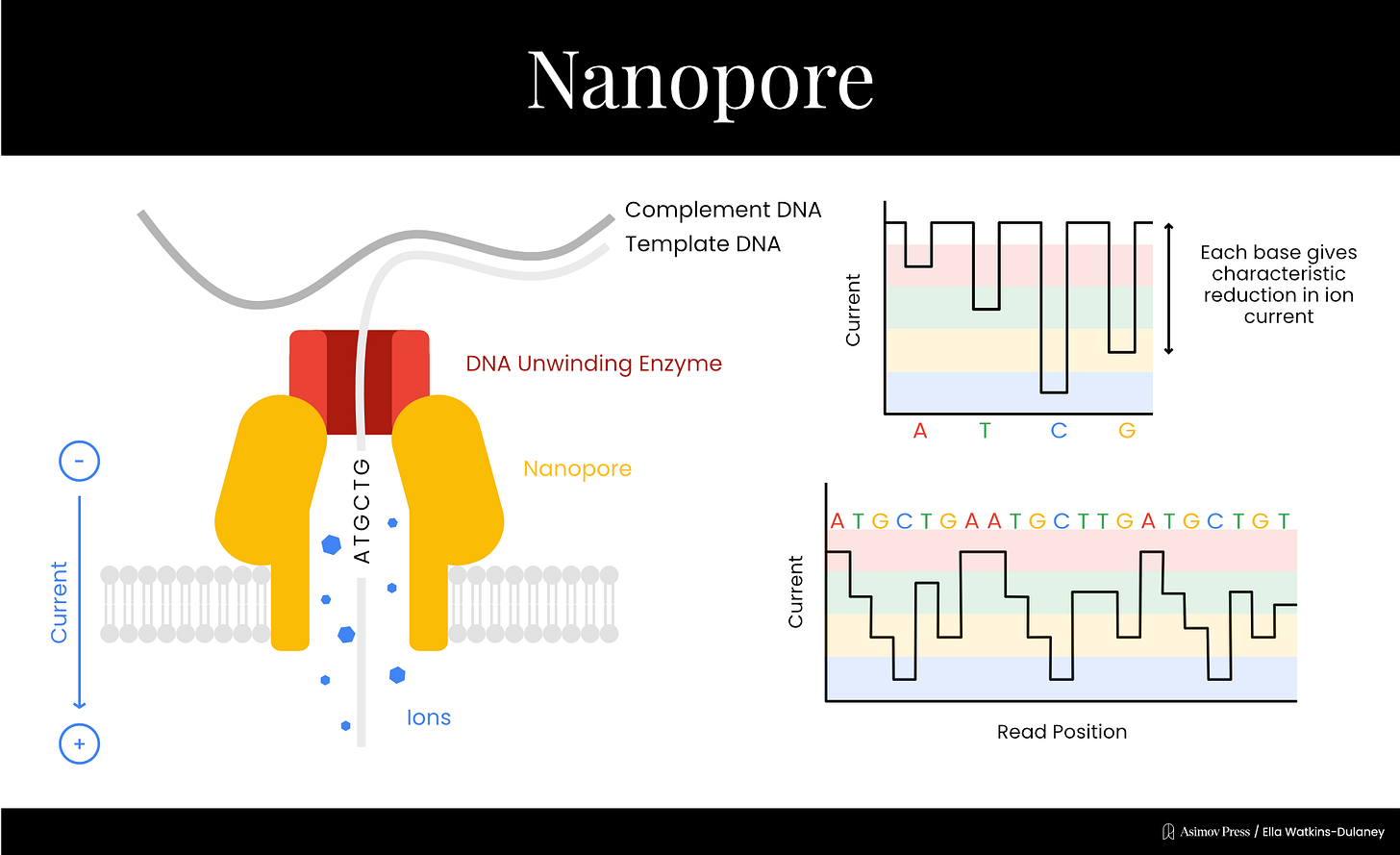

Nanopore is the most recently commercialized major sequencing method, collectively developed by several groups starting in the 1990s. A nanopore is a protein or lipid with a small hole in its center through which other materials, such as DNA, can pass. The first nanopore used for sequencing was ⍺-hemolysin, a protein toxin from the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, though other biological and synthetic nanopores have since been tested.

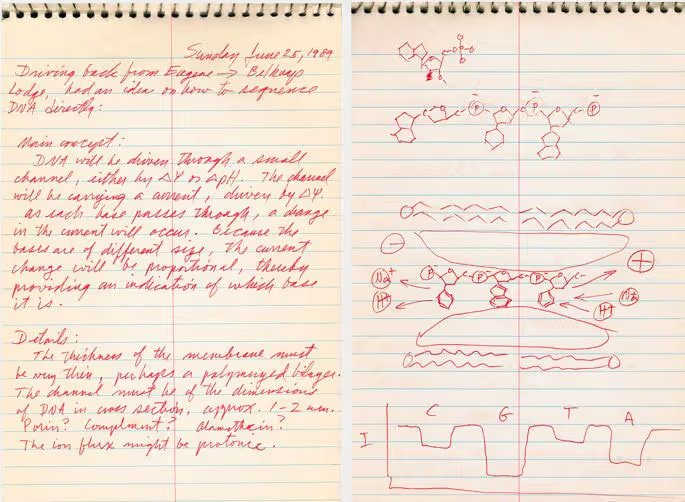

In 1996, David Deamer and Daniel Branton’s labs at UC Santa Cruz and Harvard collaborated on a paper showing that when an electric current runs through a nanopore, passing purine (A and G) and pyrimidine (T and C) DNA bases through the nanopore disrupted the current to different degrees. While the technique couldn’t yet discriminate between all four bases, the general idea for a new single-molecule sequencing method was there.

In 2001, Hagan Bayley’s lab at Texas A&M demonstrated a limited sequencing method based on the observation that correctly and incorrectly paired DNA bases disrupted nanopore current to different extents. They tethered a short piece of DNA with a few unknown bases to the entrance of the nanopore, then added other short DNA strands with different bases at the position corresponding to the unknown base on the tethered strand. By looking at which base produced the disruption corresponding to a perfect match, they could guess the unknown nucleotide.

In order to directly assess DNA strands going through the nanopore, two major problems needed solving. The first was that DNA moved too fast to reliably detect; the second was that individual bases still could not be differentiated, just purines and pyrimidines. In 2005, Bayley (who by then had moved to Oxford) made progress on the first issue, working with scientists at the Scripps Institute to slow the template DNA down by adding short “hairpin” structures that partially blocked off the pore. That year, Bayley co-founded Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) to develop the emerging sequencing method. ONT quickly brought together various technologies, licensing IP from the labs of Bayley, Deamer, Branton, and others.

In 2010, ONT combined two technologies addressing each of the main outstanding problems. The first was an engineered nanopore developed in collaboration with Bayley’s lab that could discriminate between individual DNA bases, solving the resolution issue. The second was a trick to slow the DNA down to detectable speeds, using the familiar DNA polymerase enzyme. Mark Akeson’s lab at UC Santa Cruz had identified a specific polymerase from the bacterial virus ɸ29 that replicated DNA at an ideal speed for detection via nanopore. Template DNA strands were replicated just before entering the nanopore, passing through slowly enough for individual bases’ effect on the electrical current to be detectable and allowing the DNA sequence to be read one base at a time.

By 2012, ONT had unveiled its first sequencing data, and Nanopore sequencing quickly established itself as a quick method for generating long reads without DNA synthesis, albeit with a higher error rate than some earlier methods. (Nanopore reads had an accuracy of about 85-90 percent per base in 2017, compared to over 99 percent for Illumina. Recent improvements, though, have boosted this accuracy to more than 99 percent for most applications.)

ONT released its first commercial product in 2015: a handheld machine called the MinION that retailed for just $1000, a fraction of the price of most sequencers. Subsequent releases include more traditional benchtop sequencers such as the PromethION and GridION.

Conclusion

In its early days, sequencing was a laborious (and literally radioactive) biochemical process. Today, sequencing machines are ubiquitous, safe, and much less labor-intensive. This evolution was enabled not just by advances in biochemistry but insights from biophysics and materials science, as well as manufacturing ingenuity that turned lab sequencing setups into machines ready for shipping to customers.

Ultimately, DNA sequencing technology extends beyond these five techniques, but they represent the most transformative and widely adopted methods of the past fifty years. Together, they have enabled physicians to identify disease-causing variants in patients, allowed researchers to sequence entire microbial communities from ocean water or human guts, and opened windows into deep time by recovering genomes from Neanderthals and early humans.

New sequencing methodologies are still under development, too. In 2025, Roche announced a new single-molecule technique called Sequencing by Expansion, which inserts large engineered molecules called ‘Xpandomers’ between nucleotides for more accurate detection via nanopore. Both new techniques and refinements to existing methods are aimed at further decreasing the cost of sequencing, with some groups looking to read an entire human genome for $100 or less. Ultima Genomics met this target with its UG100 sequencing machine, unveiled in 2022 and shipped in 2024. Element Biosciences’ VITARI system, announced in February and expected to ship in the second half of 2026, achieved the same price point with a smaller device. The $100 price tag advertised by these companies includes only the consumables used by the machine itself, excluding labor, data analysis, and other costs.

Anyone able to approach this target stands to benefit tremendously, given the obvious demand for DNA sequencing. For example, recent years have seen the proliferation of cohort studies focused on clinical analyses of whole-genome sequencing data. These include the Stanford ELITE study, which is focused on identifying genetic determinants of aerobic capacity, and the NIH’s All of Us Research Program, which has sequenced well over 200,000 genomes in order to study genetic diseases.

Innovation in DNA sequencing will surely continue, but these five techniques have already transformed a feat that was impossible just fifty years ago into something that can be done overnight.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly claimed that Frederick Sanger is the only individual to receive two Nobel Prizes in the same field. We apologize for the error.

Evan DeTurk is an MPhil student at Cambridge in the history of science. He writes about biology and its history on Substack. Previously, Evan researched genome editing at UC Berkeley and earned an A.B. in Molecular Biology from Princeton.

Schematics created by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Cite: DeTurk, E. “A Visual Guide to DNA Sequencing.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/58ew-79yt

While both projects sequenced DNA from multiple anonymous donors, Celera had mostly used Venter’s own DNA.

The human genome is three billion base pairs long but producing a correct sequence requires sequencing the whole thing many times over and computationally assembling all of those reads. For this reason, sequencing a human genome is much more expensive than sequencing three thousand megabases of raw DNA.

Holley’s method was distinct from Sanger’s. He began by isolating the alanine tRNA molecules and then cutting them into shorter pieces of unequal lengths, using enzymes. Then, he separated each fragment by size using column chromatography and ran various chemical techniques to figure out the sequence of each piece. Finally, he “aligned” these fragments by finding overlaps between them, thus reconstructing the full, 77-nucleotide strand.

At least, up until the maximum length created by the first DNA polymerase reaction.

DNA polymerase adds a nucleotide triphosphate to the growing DNA strand by promoting a cleavage between the phosphates. One of the three phosphates becomes part of the DNA backbone, and the other two are released as PPi.

Firefly luciferase is the enzyme found in the firefly abdomen that gives them their characteristic glow. It’s a common reporter in molecular biology because of its immediate read out and ease of detection.

The signal to noise ratio is the amount of an observed effect due to the intended process compared to other “background noise”. In this case, light resulting from nucleotide addition versus other chemical reactions. Luciferase recognizes and acts on dATP in solution, creating a spurious signal unrelated to nucleotide addition, which must be accounted for during analysis. Fortunately, the modified “A” nucleotide effectively suppresses this side reaction, improving the signal to noise ratio.

/uploads/spam-screenshot.png)

/uploads/UglySpam.png)

/uploads/Warning.png)

/uploads/freespins.png)