Recently my wife and I needed to call a car, so out came the apps to compare rideshare prices. There’s always a bit of variation here, but this time was striking.

My wife’s Uber app quoted her $28, while mine gave me $47. Same app, time, and place - but two wildly-different prices.

Who knows why? I’m usually more willing to spend than she is, and I bet that's represented on my user profile. I was paying with a gift card, which surely contributes. Maybe it was a price scraping update, comparison shopping detection, or a system that explores “face-in-the-door” high prices before backing down. From the outside, no one really knows.

That makes me worry. When prices are based on behavior, they incentivize us to behave performatively - after all, the squeaky wheel gets the grease.

Paying different prices is nothing new

Price discrimination has existed for approximately forever - like senior discounts, or coupon books. A business can make a little more money by selectively lowering prices for people who can jump through certain hoops (and might not buy without the discount).

In this simplified demand curve, if the price is $9, then the business only earns $45.

By pricing at $10 for most, with a $1 discount for the price-sensitive blue buyer, the business earns $49 instead.

Behavioral discrimination isn’t a new practice either. When your internet service provider tells you they’re raising rates, do you pay up? Or do you call customer service, wait on hold, threaten to cancel, get transferred to “retention”, and learn about some exciting new discounts that you qualify for? Not everyone has the time or patience to run this gauntlet - and that’s exactly why businesses do it.

When you bring price discrimination into the digital world, there’s nothing different in any individual case. But as the apocryphal Stalin quote goes, quantity has a quality all of its own. Technology gives us not only quantity, but ubiquity - every piece of behavioral context can contribute to your prices.

The foundation for pervasive price discrimination is already here

Unlike in meatspace, every digital action can be cheaply recorded and analyzed.

One example is the “abandoned cart” discount, which is so standard that Shopify and Etsy have step-by-step instructions to set it up as a seller. If you add something to your cart but don’t check out, you might get an email reminder later and a little discount to push you over the finish line. With that knowledge, I find myself abandoning carts even when the price was fine before, on the off chance that a discount materializes.

If you ever try to cancel an Amazon Prime membership, they’ll parade you through a dozen webpages and offers to try and keep you around. The last time I canceled a niche SaaS tool, I was surprised to see the same: Another week free? Another month for a dollar? Please don’t go! I didn’t expect this level of sophistication from a small company. Of course, it wasn’t 100% custom - just the work of Churnkey, a “retention automation” company making the classic please-don’t-cancel discount into a standard practice.

We often think about price discrimination as a discount - great when we benefit, no big deal when we have to pay full price. But what about when you get a “special deal” to pay extra?

In December 2025, Groundwork Collective found that Instacart was charging individualized prices. Some people paid 23% more for the exact same item, from the exact same store, at the exact same time.

In Instacart’s response, they said that these pricing experiments were based purely on behavioral data - not on personal or demographic information. Or in other words, they aren’t looking at who you are, “just” what you’re doing.

Andy Warhol once wrote about American culture:

What's great about this country is America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest.

You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you can know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too.

A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.

From The Philosophy of Andy Warhol

Yesterday, we all drank the same Cokes. But today, we scroll hyper-personalized social media feeds, tailored to our so-called revealed preferences. And tomorrow, maybe we’ll pay wildly-different prices for that same can of Coke (and not because you’re Liz Taylor, but because you spend like she does). It’s one more change that fragments our common experiences into isolated silos.

Personal pricing leads to ritualized posturing

Economically, is this an issue? I don’t really know; if Lucille Bluth is willing to pay $10 for a banana, maybe we should let her - and the shop and platform can split the profits from whatever pricing scheme can make that happen. It’s the invisible hand at work.

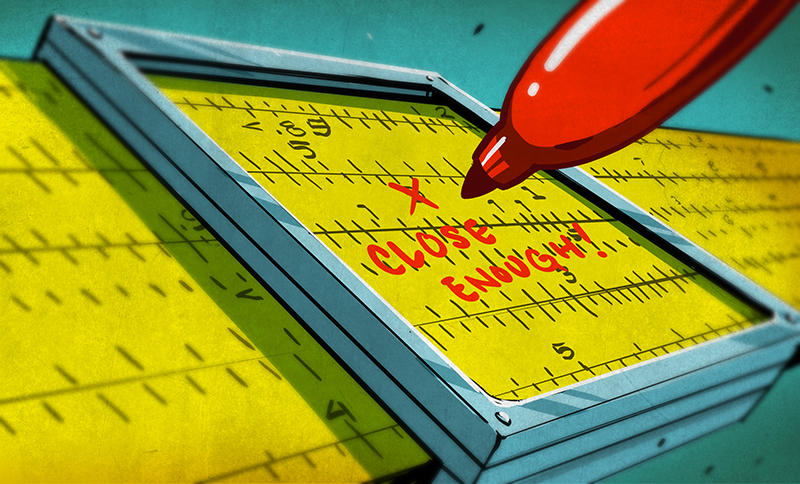

It still gives me the ick. It makes me feel like the business is trying to shrink my “consumer surplus” until I pay a perfect, maximized-for-me price. It makes me feel like an adversary, not a customer, and it makes me feel like I should be a worse person to get a better price.

Is it just a cultural difference? As a kid visiting China, I once bought a Gameboy game from a nice lady at the electronics bazaar, a great deal at under $10, or so I thought. Later, I got scolded because I didn’t try to haggle: Remember, the first price they offer is just a starting point to negotiate.

I think this new price discrimination - of abandoned carts, the cancellation song-and-dance, and customers segmented down to individuals - is different. The social expectations are flipped: I don’t think the average person knows that haggling is even an option, nor what factors contribute to personalized pricing.

Only a dummy like me goes to the bazaar without haggling. But today, you probably don’t try to abandon every cart, or switch apps in a way that’s easily-identifiable as comparison shopping, or only buy things that indicate you’re a regular person instead of a fancy rich person. You might let mistakes slide instead of filing a complaint or blasting a company in a Yelp review. All of those events (and who knows which exactly?) are potentially recorded and fed back into your personalized price.

In the future, it’ll be a quiet trick to cultivate your digital reputation of being picky, so you can get the lowest prices and the best treatment. You might even resell that access to someone who wasn’t so careful; or equally likely, spiral into superstitious practice since opaque pricing means you never really know what happened.

On the flip side, we might see the “most favored customer” clause make its way from B2B to consumer contexts - an explicit admission that “the customer is king” is dead. It’ll be an arms race, with data-crunchers looking for opportunities to raise prices while we posture about where we really draw the line.

—

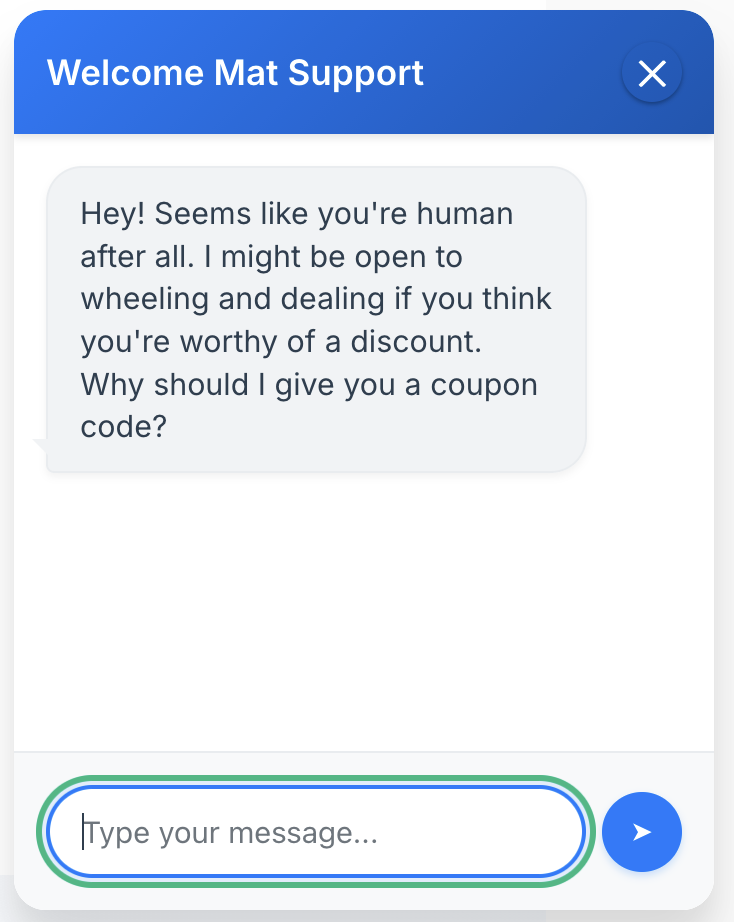

I recently got a kick out of the whimsical CAPTCHA Welcome Mat, a site where you have to prove your humanity before you’re allowed to buy the product. In the bonus round, you get to haggle with a chatbot to earn a coupon for 10% off.

I enjoyed playing that game… once. But I would prefer to be sincere rather than performative, and I don’t love that sincerity is becoming the more expensive option.