Well! Last week was an unexpectedly exciting one here at Cognitive Resonance HQ (aka my house) after The Verge published my essay explaining why large-language models are not on the path to general intelligence, because language is not the same as thought. Forgive the crowing, but if I may: Yann LeCunn, the outgoing chief AI scientist at Meta, posted about it favorably on LinkedIn; Alison Gopnik, a cognitive scientist I’ve long admired, described it as “excellent and very clear”; and I picked up more than 200 new followers to this newsletter—welcome, y’all! (Yes, I live in Texas. Yee-haw.)

Given this interest, I thought this week I’d address two of the main critiques of my argument. Before continuing, if you need to build some background knowledge on this topic, the entire essay is re-published below (with The Verge’s permission)—and regular readers may note that it borrows liberally from several previous essays published here, including my interview of neuroscientist Ev Fedorenko (more from her later).

But now let’s get into the pushback. Basically, we’ve got two groups of people who think I’m very mistaken about the future of AI, although interestingly their critiques are diametrically opposed to each other. I’m calling the first group the “wing flappers” and the second the “cognitive pluralists.”

The wing flappers believe that my argument fails because I mistakenly assume that the only way to get to artificial general intelligence is by emulating human intelligence. “Cutting-edge research shows airplanes do not work the same as birds, [so] the entire airline industry is a bubble ignoring this,” said someone on Reddit, thinking they zinged me but good. The theory here seems to be that because there’s so much data that’s used to train LLMs, perhaps that’s sufficient in and of itself to achive general intelligence. “Written language stores thought,” wrote one particularly aggravated commentor on The Verge, “so LLMs are learning from the knowledge stored by language.”

On its face, this is a plausible hypothesis about how we might achieve artificial general intelligence. But the number of plausible predictive theories will always exceed the number that actually are true, and I think this perspective suffers from at least three flaws.

The first problem with this counterargument is one I briefly allude to in my essay, which is that there’s a non-trivial amount of human knowledge that sits outside of our language. The philosopher of science Michael Polanyi described this as “tacit knowledge,” the sort of things we know how to do but cannot easily explain. Riding a bike is one common example, but also applies to activities such as playing a musical instrument, or solving a jigsaw puzzle, the sort of things we typically learn how to do from interactive experience. There’s even a growing scientific effort around “embodied cognition” that builds off this notion, and researchers in this area are actively investigating how animals (including humans) develop certain cognitive capacities that may not rely exclusively on mental representations in the brain. Whether one buys into that or not, the point remains that linguistic information codified in writing provides an expansive yet ultimately limited database of knowledge.

As computer scientist Deb Raji observes, “there is no dataset that will be able to capture the full complexity of the details of existence, in the same way that there can be no museum to contain the full catalog of everything in the whole wide world”—more on this here in an essay featuring Grover from Sesame Street.

The second problem the wing flappers face is that “intelligence” as a concept is much fuzzier than something like, say, “flying.” When it comes to the latter, either the thing we care about is successfully locomoting through the air, or not—there’s an objective definition of success. The same simply cannot be said whether something is manifesting “intelligence”—consider, for example, that there’s been a long-running debate in cognitive science over whether a household thermostat manifests intelligent behavior. If we abandon using human cognitive processes as our baseline for developing and evaluating the behavior of artificial systems, it’s not at all clear what should take its place. The Wright Brothers at least had aerodynamic data to work with.

Similarly, the third flaw with this counterargument is that generative AI as it exists today arises from explicit efforts to model human cognitive processes, in our brains! For several decades, cognitive scientists operating in the “connectionist” school have argued that the process that we use to process information through neurons could be simulated artificially, and they’ve diligently worked to build such models digitally. We call them “artificial neural networks” for a reason, they are explicitly premised on a theory of how our brains function. And it turns out that with enough computing power—and especially the capacity to process information in parallel—you can indeed develop an AI system that can, with a lot of human tuning, fluidly process an incredibly diverse array of input. Geoffrey Hinton deserves his Nobel Prize! But it is profoundly odd to argue that, having used the human brain as the model to get us where we are today with generative AI, we should now chuck it aside.

That’s enough on wing flapping, now let’s turn to the second group of critics, the “cognitive pluralists. ” Unlike the flappers, the pluralists believe that we should be modeling AI systems with human intelligence as our north star. And they largely agree with me that there is a broad range of cognitive capabilities that go beyond what’s captured in linguistic data. But the cognitive pluralists believe we can, and likely will, achieve something akin to AGI by stitching together digital emulations of these various capacities in a multi-modal AI system. Frankenstein, but for intelligence.

Look, I also anticipated this objection, and pointed to a new definition of AGI that many AI luminaries recently signed on to as begging many questions about what exactly should be included or excluded in their definition of intelligence—a construct validity question. But even if we hand-wave that away and assume the pluralists have the right goal in mind—a very big assumption indeed—they are all over the map in what it’ll take to get there. Consider the following theories from various AI bigwigs:

Sundar Pichai says that AI models can surmount the limitations of language by being trained on “video, text, images and code,” he seems to think multimodality is literally all we need;

Yann LeCun is leaving Meta to found an AI startup that will focus on building AI with “world models”;

Yoshua Bengio has been working on capturing the “flow state” of the brain as a dynamical system;

Gary Marcus maintains that AI will need to be able to manipulate symbols (“neurosymbolic AI”) to ever match or surpass human intelligence; and

Ilya Sutskever hints that AGI will only arrive if we discover a new way to simulate human generalization using sparse data, seemingly using some evolutionary-like method.

So many men, so many different dreams of superintelligence. Whether any of them will be realized, however, is unknown. No one knows! My point remains that scaling up linguistic data will not be sufficient to deliver omniscient robots that will bring forth our glorious abundant future. That’s it, that’s my stake in the ground.

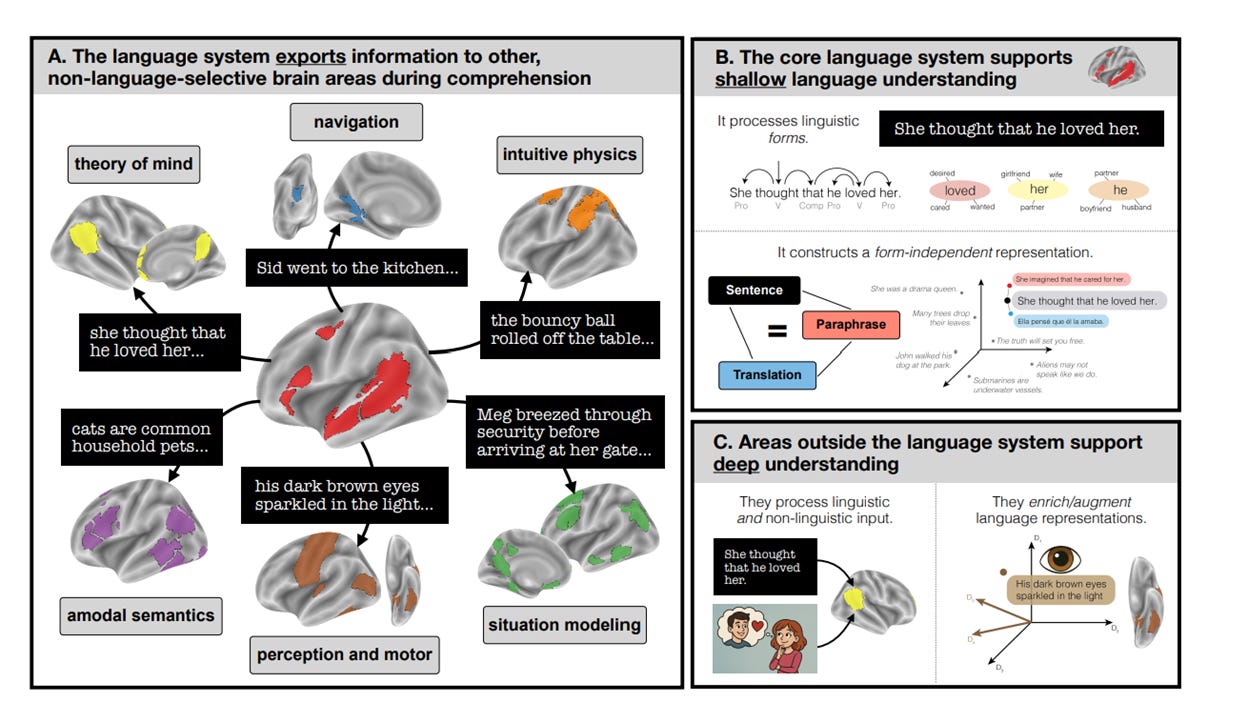

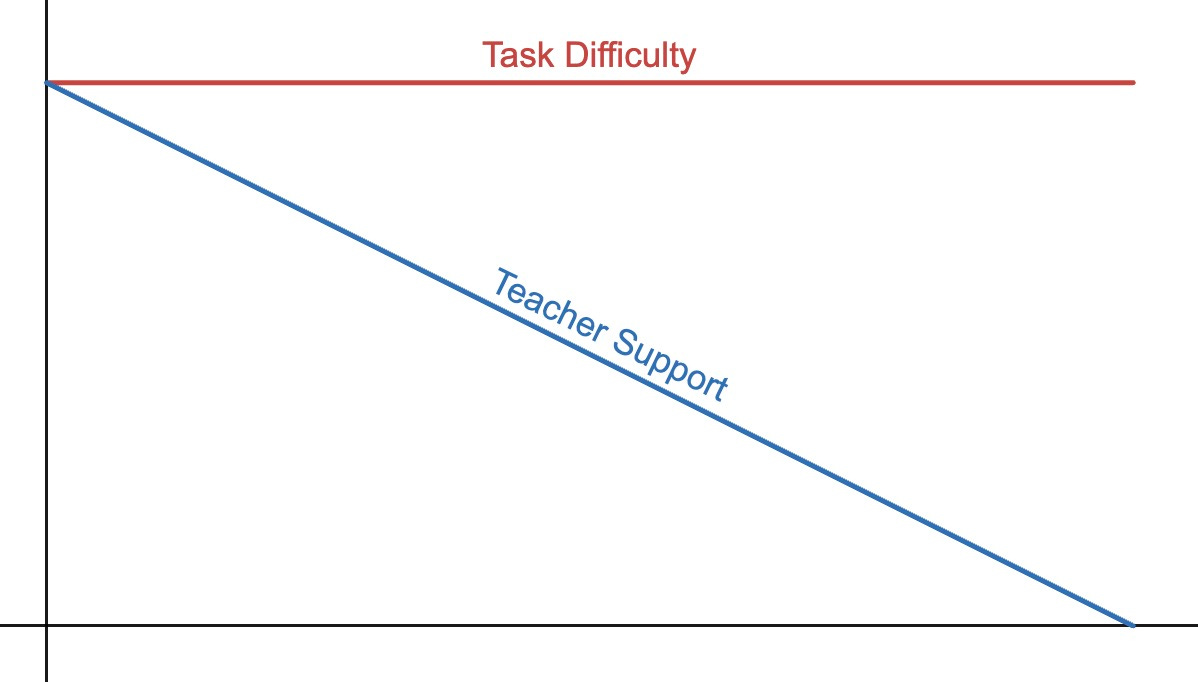

In the meantime, we should continue to pursue scientific research on how we humans think, and compare and contrast this to how AI models do what they do. To that end, in a bit of fortuitous timing, just last week a group of researchers—including Ev Fedorenko yet again—published an interesting paper that offers a conceptual model for how humans “export” linguistic information to interact with our other cognitive capacities. They posit a model that looks something like this:

Note that under this model, our core language system is limited to “shallow” understanding of linguistic forms, whereas other cognitive capacities support “deep understanding.” These researchers then ask an important question that speaks to the “known unknowns” of the AI scientific frontier: “Do any AI systems understand language deeply? If so, then we might expect them to show signatures of exportation. Several recent studies have attempted to explicitly build exportation into AI systems by augmenting LLMs with diverse extralinguistic systems: vision models, physics engines, formal logic provers, theory of mind engines, memory augmentations, and many more.”

Note the word “attempted”—there’s no breakthroughs yet. Again, we simply do not know how any of this will shake out. In the meantime, I will repeat my call to adopt an adversarial mindset when it comes all things AI related, including whether we’re on the path to AGI or superintelligence. Be skeptical. Be critical. Be thoughtful!

Now onto the essay…

Large Language Mistake

Cutting-edge research shows language is not the same as intelligence. The entire AI bubble is built on ignoring it.

“Developing superintelligence is now in sight,” says Mark Zuckerberg, heralding the “creation and discovery of new things that aren’t imaginable today.” Powerful AI “may come as soon as 2026 [and will be] smarter than a Nobel Prize winner across most relevant fields,” says Dario Amodei, offering the doubling of human lifespans or even “escape velocity” from death itself. “We are now confident we know how to build AGI,” says Sam Altman, referring to the industry’s holy grail of artificial general intelligence — and soon superintelligent AI “could massively accelerate scientific discovery and innovation well beyond what we are capable of doing on our own.”

Should we believe them? Not if we trust the science of human intelligence, and simply look at the AI systems these companies have produced so far.

The common feature cutting across chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Google’s Gemini, and whatever Meta is calling its AI product this week are that they are all primarily “large language models.” Fundamentally, they are based on gathering an extraordinary amount of linguistic data (much of it codified on the internet), finding correlations between words (more accurately, sub-words called “tokens”), and then predicting what output should follow given a particular prompt as input. For all the alleged complexity of generative AI, at their core they really are models of language.

The problem is that according to current neuroscience, human thinking is largely independent of human language — and we have little reason to believe ever more sophisticated modeling of language will create a form of intelligence that meets or surpasses our own. Humans use language to communicate the results of our capacity to reason, form abstractions, and make generalizations, or what we might call our intelligence. We use language to think, but that does not make language the same as thought. Understanding this distinction is the key to separating scientific fact from the speculative science fiction of AI-exuberant CEOs.

The AI hype machine relentlessly promotes the idea that we’re on the verge of creating something as intelligent as humans, or even “superintelligence” that will dwarf our own cognitive capacities. If we gather tons of data about the world, and combine this with ever more powerful computing power (read: Nvidia chips) to improve our statistical correlations, then presto, we’ll have AGI. Scaling is all we need.

But this theory is seriously scientifically flawed. LLMs are simply tools that emulate the communicative function of language, not the separate and distinct cognitive process of thinking and reasoning, no matter how many data centers we build.

Last year, three scientists published a commentary in the journal Nature titled, with admirable clarity, “Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought.” Co-authored by Evelina Fedorenko (MIT), Steven T. Piantadosi (UC Berkeley) and Edward A.F. Gibson (MIT), the article is a tour de force summary of decades of scientific research regarding the relationship between language and thought, and has two purposes: one, to tear down the notion that language gives rise to our ability to think and reason, and two, to build up the idea that language evolved as a cultural tool we use to share our thoughts with one another.

Let’s take each of these claims in turn.

When we contemplate our own thinking, it often feels as if we are thinking in a particular language, and therefore because of our language. But if it were true that language is essential to thought, then taking away language should likewise take away our ability to think. This does not happen. I repeat: Taking away language does not take away our ability to think. And we know this for a couple of empirical reasons.

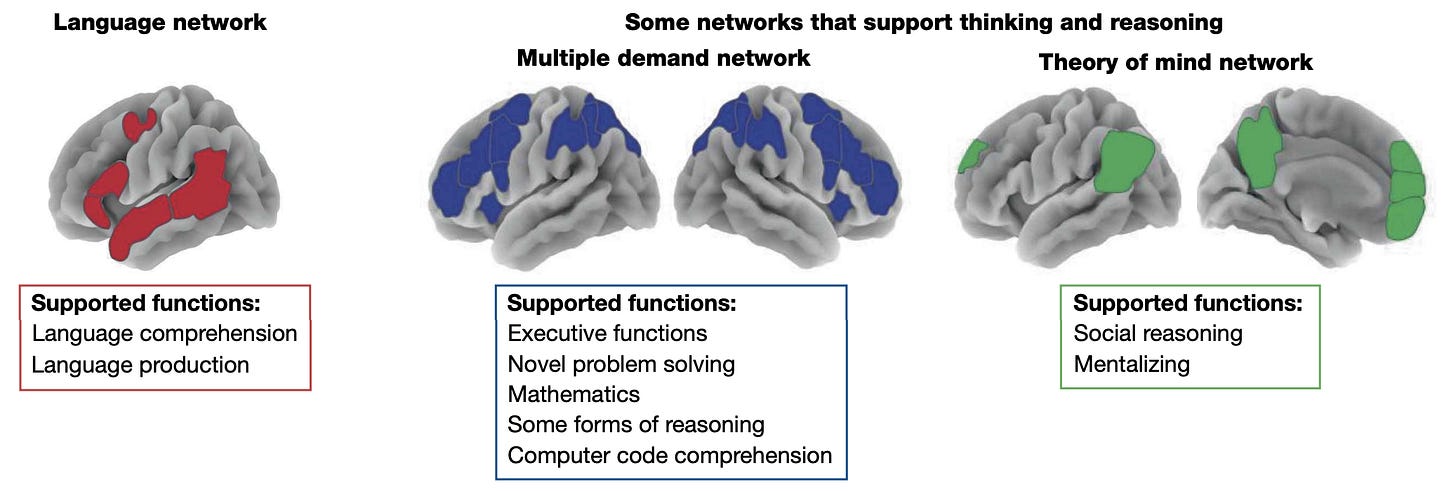

First, using advanced functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we can see different parts of the human brain activating when we engage in different mental activities. As it turns out, when we engage in various cognitive activities — solving a math problem, say, or trying understand what is happening in the mind of another human — different parts of our brains “light up” as part of networks that are distinct from our linguistic ability:

Second, studies of humans who have lost their language abilities due to brain damage or other disorders demonstrate conclusively that this loss does not fundamentally impair the general ability to think. “The evidence is unequivocal,” Fedorenko et al. state, that “there are many cases of individuals with severe linguistic impairments … who nevertheless exhibit intact abilities to engage in many forms of thought.” These people can solve math problems, follow nonverbal instructions, understand the motivation of others, and engage in reasoning — including formal logical reasoning and causal reasoning about the world.

If you’d like to independently investigate this for yourself, here’s one simple way: Find a baby and watch them (when they’re not napping). What you will no doubt observe is a tiny human curiously exploring the world around them, playing with objects, making noises, imitating faces, and otherwise learning from interactions and experiences. “Studies suggest that children learn about the world in much the same way that scientists do—by conducting experiments, analyzing statistics, and forming intuitive theories of the physical, biological and psychological realms,” the cognitive scientist Alison Gopnik notes, all before learning how to talk. Babies may not yet be able to use language, but of course they are thinking! And every parent knows the joy of watching their child’s cognition emerge over time, at least until the teen years.

So, scientifically speaking, language is only one aspect of human thinking, and much of our intelligence involves our non-linguistic capacities. Why then do so many of us intuitively feel otherwise?

This brings us to the second major claim in the Nature article by Fedorenko et al., that language is primarily a tool we use to share our thoughts with one another — an “efficient communication code,” in their words. This is evidenced by the fact that, across the wide diversity of human languages, they share certain common features that make them “easy to produce, easy to learn and understand, concise and efficient for use, and robust to noise.”

Without diving too deep into the linguistic weeds here, the upshot is that human beings, as a species, benefit tremendously from using language to share our knowledge, both in the present and across generations. Understood this way, language is what the cognitive scientist Cecilia Heyes calls a “cognitive gadget” that “enables humans to learn from others with extraordinary efficiency, fidelity, and precision.”

Our cognition improves because of language — but it’s not created or defined by it.

Take away our ability to speak, and we can still think, reason, form beliefs, fall in love, and move about the world; our range of what we can experience and think about remains vast.

But take away language from a large language model, and you are left with literally nothing at all.

An AI enthusiast might argue that human-level intelligence doesn’t need to necessarily function in the same way as human cognition. AI models have surpassed human performance in activities like chess using processes that differ from what we do, so perhaps they could become superintelligent through some unique method based on drawing correlations from training data.

Maybe! But there’s no obvious reason to think we can get to general intelligence — not improving narrowly defined tasks —through text-based training. After all, humans possess all sorts of knowledge that is not easily encapsulated in linguistic data — and if you doubt this, think about how you know how to ride a bike.

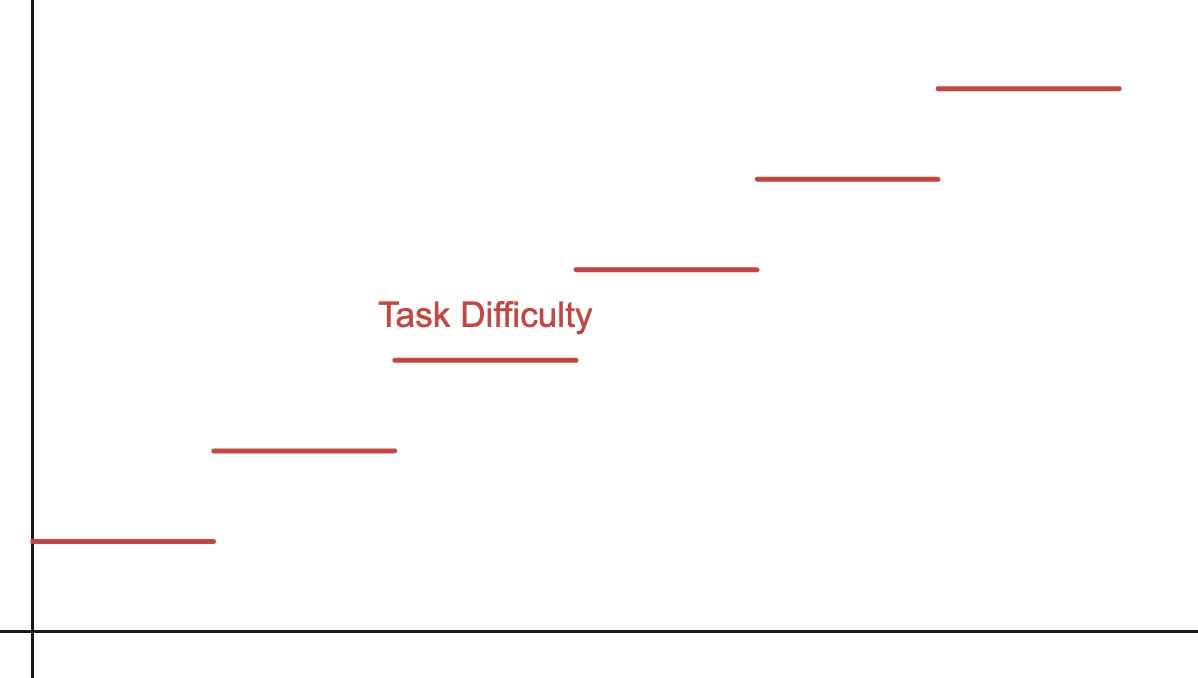

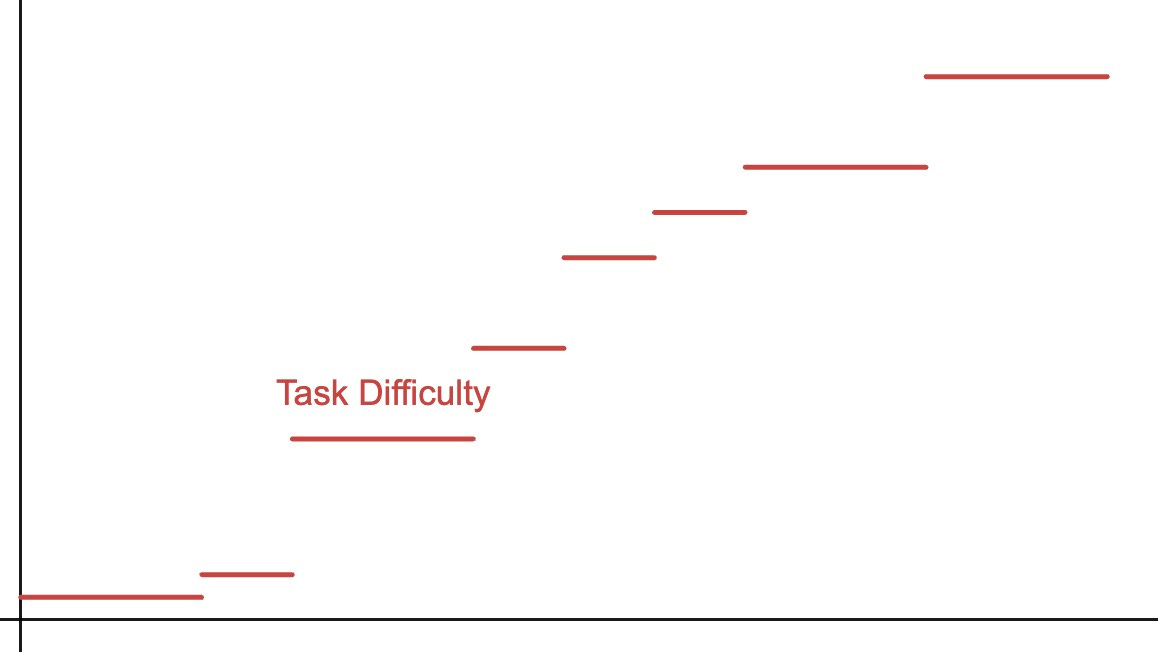

In fact, within the AI research community there is growing awareness that LLMs are, in and of themselves, insufficient models of human intelligence. For example, Yann LeCun, a Turing Award winner for his AI research and a prominent skeptic of LLMs, left his role at Meta last week to found an AI startup developing what are dubbed world models: “systems that understand the physical world, have persistent memory, can reason, and can plan complex action sequences.” And recently, a group of prominent AI scientists and “thought leaders” — including Yoshua Bengio (another Turing Award winner), former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, and noted AI skeptic Gary Marcus — coalesced around a working definition of AGI as “AI that can match or exceed the cognitive versatility and proficiency of a well-educated adult” (emphasis added). Rather than treating intelligence as a “monolithic capacity,” they propose instead we embrace a model of both human and artificial cognition that reflects “a complex architecture composed of many distinct abilities.”

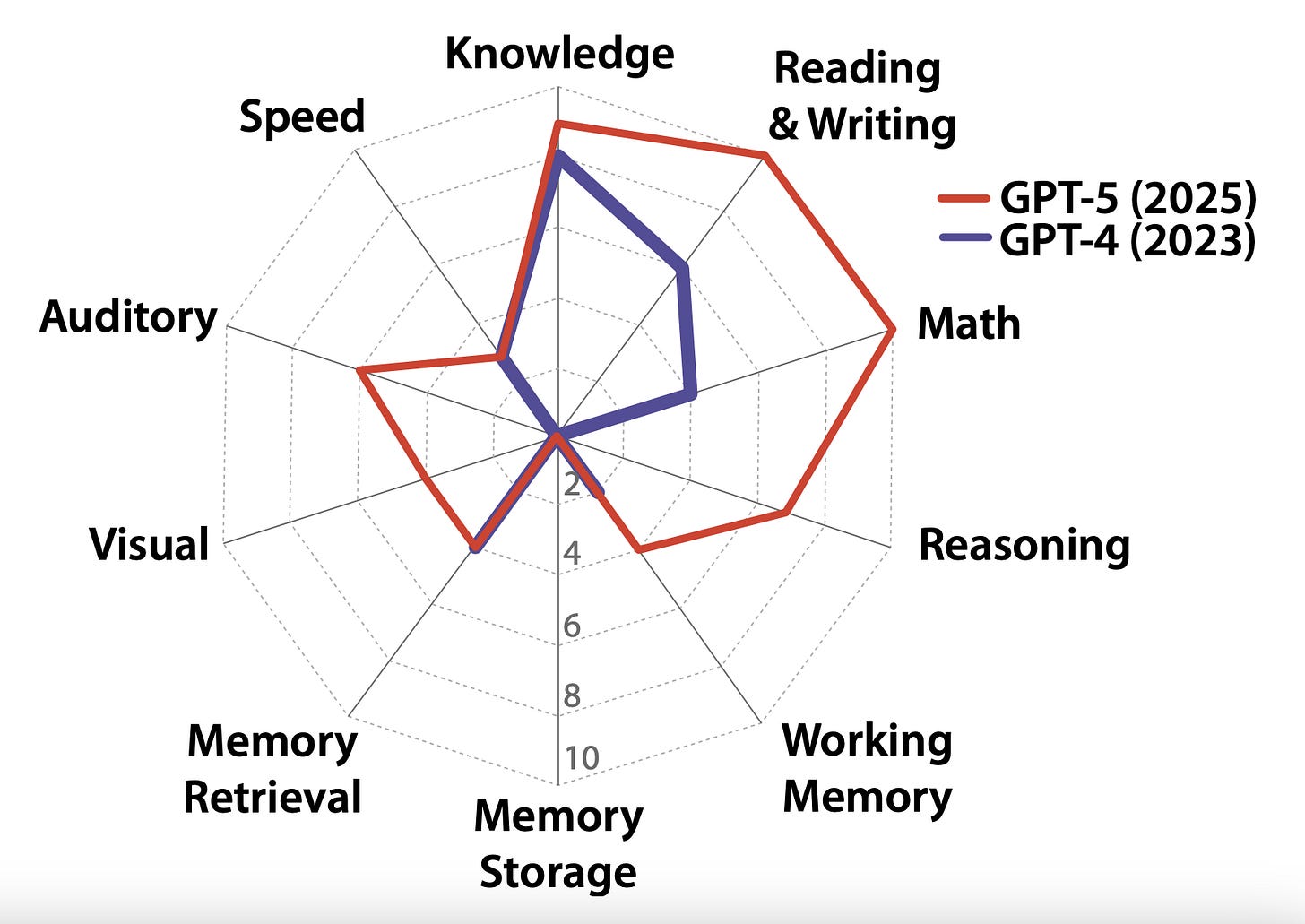

They argue intelligence looks something like this:

Is this progress? Perhaps, insofar as this moves us past the silly quest for more training data to feed into server racks. But there are still some problems. Can we really aggregate individual cognitive capabilities and deem the resulting sum to be general intelligence? How do we define what weights they should be given, and what capabilities to include and exclude? What exactly do we mean by “knowledge” or “speed,” and in what contexts? And while these experts agree simply scaling language models won’t get us there, their proposed paths forward are all over the place — they’re offering a better goalpost, not a roadmap for reaching it.

Whatever the method, let’s assume that in the not-too-distant future, we succeed in building an AI system that performs admirably well across the broad range of cognitive challenging tasks reflected in this spiderweb graphic. Will we have achieved building an AI system that possesses the sort of intelligence that will lead to transformative scientific discoveries, as the Big Tech CEOs are promising? Not necessarily. Because there’s one final hurdle: Even replicating the way humans currently think doesn’t guarantee AI systems can make the cognitive leaps humanity achieves.

We can credit Thomas Kuhn and his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions for our notion of “scientific paradigms,” the basic frameworks for how we understand our world at any given time. He argued these paradigms “shift” not as the result of iterative experimentation, but rather when new questions and ideas emerge that no longer fit within our existing scientific descriptions of the world. Einstein, for example, conceived of relativity before any empirical evidence confirmed it. Building off this notion, the philosopher Richard Rorty contended that it is when scientists and artists become dissatisfied with existing paradigms (or vocabularies, as he called them) that they create new metaphors that give rise to new descriptions of the world — and if these new ideas are useful, they then become our common understanding of what is true. As such, he argued, “common sense is a collection of dead metaphors.”

As currently conceived, an AI system that spans multiple cognitive domains could, supposedly, predict and replicate what a generally intelligent human would do or say in response to a given prompt. These predictions will be made based on electronically aggregating and modeling whatever existing data they have been fed. They could even incorporate new paradigms into their models in a way that appears human-like. But they have no apparent reason to become dissatisfied with the data they’re being fed — and by extension, to make great scientific and creative leaps.

Instead, the most obvious outcome is nothing more than a common-sense repository. Yes, an AI system might remix and recycle our knowledge in interesting ways. But that’s all it will be able to do. It will be forever trapped in the vocabulary we’ve encoded in our data and trained it upon — a dead-metaphor machine. And actual humans — thinking and reasoning and using language to communicate our thoughts to one another — will remain at the forefront of transforming our understanding of the world.

My thanks to the terrific editing team at The Verge who helped polish my prose (and push my thinking), and to Dr. Adam Dubé at McGill University for making the introduction.