I have a credit card with HSBC1. It doesn’t see much use2, but I still get a monthly statement from them, and an email to say it’s available.

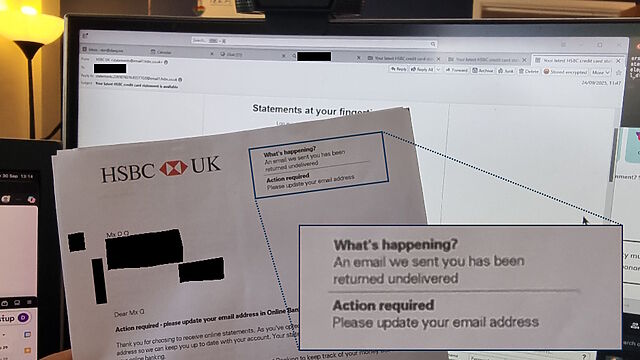

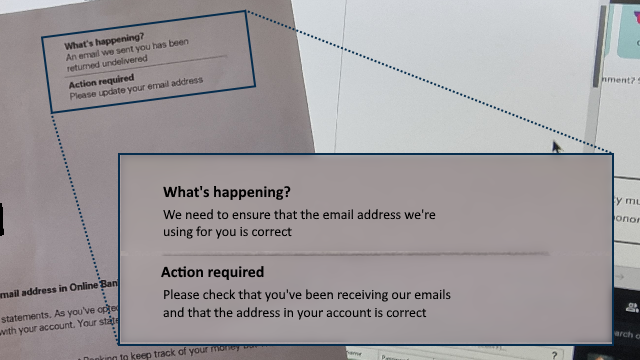

Not long ago I received a letter from them telling me that emails to me were being “returned undelivered” and they needed me to update the email address on my account.

“What’s happening?”

I logged into my account, per the instructions in the letter, and discovered my correct email address already right there, much to my… lack of surprise3.

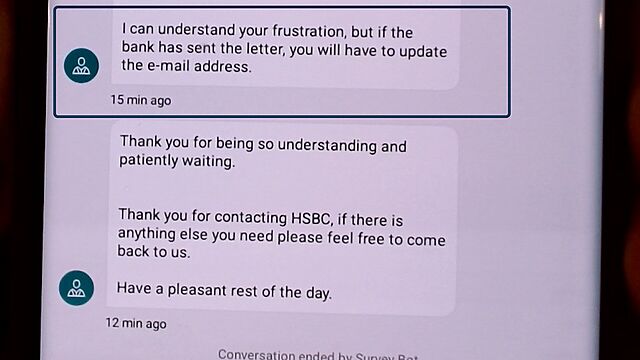

So I kicked off a live chat via their app, with an agent called Ankitha. Over the course of a drawn-out hour-long conversation, they repeatedly told to tell me how to update my email address (which was never my question). Eventually, when they understood that my email address was already correct, then they concluded the call, saying (emphasis mine):

I can understand your frustration, but if the bank has sent the letter, you will have to update the e-mail address.

This is the point at which a normal person would probably just change the email address in their online banking to a “spare” email address.

But aside from the fact that I’d rather not4, by this point I’d caught the scent of a deeper underlying issue. After all, didn’t I have a conversation a little like this one but with a different bank, about four years ago?

So I called Customer Services directly5, who told me that if my email address is already correct then I can ignore their letter.

I suggested that perhaps their letter template might need updating so it doesn’t say “action required” if action is not required. Or that perhaps what they mean to say is “action required: check your email address is correct”.

So anyway, apparently everything’s fine… although I reserved final judgement until I’d seen that they were still sending me emails!

“Action required”

I think I can place a solid guess about what went wrong here. But it makes me feel like we’re living in the Darkest Timeline.

I dissected HSBC’s latest email to me: it was of the “your latest statement is available” variety. Deep within the email, down at the bottom, is this code:

<img src="http://www.email1.hsbc.co.uk:8080/Tm90IHRoZSByZWFsIEhTQkMgcGF5bG9hZA==" width="1" height="1" alt=""> <img src="http://www.email1.hsbc.co.uk:8080/QWxzbyBub3QgcmVhbCBIU0JDIHBheWxvYWQ=" width="1" height="1" alt="">

What you’re seeing are two tracking pixels: tiny 1×1 pixel images, usually transparent or white-on-white to make them even-more invisible, used to surreptitiously track when somebody reads an email. When you open an email from HSBC – potentially every time you open an email from them – your email client connects to those web addresses to get the necessary images. The code at the end of each identifies the email they were contained within, which in turn can be linked back to the recipient.

You know how invasive a read-receipt feels? Tracking pixels are like those… but turned up to eleven. While a read-receipt only says “the recipient read this email” (usually only after the recipient gives consent for it to do so), a tracking pixel can often track when and how often you refer to an email6.

If I re-read a year-old email from HSBC, they’re saying that they want to know about it.

But it gets worse. Because HSBC are using http://, rather than https:// URLs for their tracking pixels, they’re also saying that every time you read an email from them, they’d like everybody on the same network as you to be able to know that you did so, too. If you’re at my house, on my WiFi, and you open an email from HSBC, not only might HSBC know about it, but I might know about it too.

An easily-avoidable security failure there, HSBC… which isn’t the kind of thing one hopes to hear about a bank!

But… tracking pixels don’t actually work. At least, they doesn’t work on me. Like many privacy-conscious individuals, my devices are configured to block tracking pixels (and a variety of other instruments of surveillance capitalism) right out of the gate.

This means that even though I do read most of the non-spam email that lands in my Inbox, the sender doesn’t get to know that I did so unless I choose to tell them. This is the way that email was designed to work, and is the only way that a sender can be confident that it will work.

But we’re in the Darkest Timeline. Tracking pixels have become so endemic that HSBC have clearly come to the opinion that if they can’t track when I open their emails, I must not be receiving their emails. So they wrote me a letter to tell me that my emails have been “returned undelivered” (which seems to be an outright lie).

Surveillance capitalism has become so ubiquitous that it’s become transparent. Transparent like the invisible spies at the bottom of your bank’s emails.

So in summary, with only a little speculation:

- Surveillance capitalism became widespread enough that HSBC came to assume that tracking pixels have bulletproof reliability.

- HSBC started using tracking pixels them to check whether emails are being received (even though that’s not what they do when they are reliable, which they’re not).

- (Oh, and their tracking pixels are badly-implemented, if they worked they’d “leak” data to other people on my network7.)

- Eventually, HSBC assumed their tracking was bulletproof. Because HSBC couldn’t track how often, when, and where I was reading their emails… they posted me a letter to tell me I needed to change my email address.

What do I think HSBC should do?

Instead of sending me a misleading letter about undelivered emails, perhaps a better approach for HSBC could be:

- At an absolute minimum, stop using unencrypted connections for tracking pixels. I do not want to open a bank email on a cafe’s public WiFi and have everybody in the cafe potentially know who I bank with… and that I just opened an email from them! I certainly don’t want attackers injecting content into the bottom of legitimate emails.

- Stop assuming that if somebody blocks your attempts to spy on them via your emails, it means they’re not getting your emails. It doesn’t mean that. It’s never meant that. There are all kinds of reasons that your tracking pixels might not work, and they’re not even all privacy-related reasons!

- Or, better yet: just stop trying to surveil your customers’ email habits in the first place? You already sit on a wealth of personal and financial information which you can, and probably do, data-mine for your own benefit. Can you at least try to pay lip service to your own published principles on the ethical use of data and, if I may quote them, “use only that data which is appropriate for the purpose” and “embed privacy considerations into design and approval processes”.

- If you need to check that an email address is valid, do that, not an unreliable proxy for it. Instead of this letter, you could have sent an email that said “We need to check that you’re receiving our emails. Please click this link to confirm that you are.” This not only achieves informed consent for your tracking, but it can be more-secure too because you can authenticate the user during the process.

Also, to quote your own principles once more: when you make a mistake like assuming your spying is a flawless way to detect the validity of email addresses, perhaps you should “be transparent with our customers and other stakeholders about how we use their data”.

Wouldn’t that be better than writing to a customer to say that their emails are being returned undelivered (when they’re not)… and then having your staff tell them that having received such an email they have no choice but to change the email address they use (which is then disputed by your other staff)?

</rant>

Footnotes

1 You know, the bank with virtue-signalling multiculturalism that we used to joke about.

2 Long, long ago I also had a current account with HSBC which I forgot to close when I switched banks… 20 years ago… and I possibly still owe them for the six pence the account was in debt at the time.

3 After all, I’d been reading their emails!

4 After all, as I’ll stress again: the email address HSBC have for me, and are using, is already correct.

5 In future, I’ll just do this in the first instance. The benefits of live chat being able to be done “in the background” while one gets on with some work are totally outweighed when the entire exchange takes an hour only to reach an unsatisfactory conclusion, whereas a telephone call got things sorted (well hopefully…) within 10 minutes.

6 A tracking pixel can also collect additional personal information about you, such as your IP address at the time that you opened the email, which might disclose your location.

7 It could be even worse still, actually! A sophisticated attacker could “inject” images into the bottom of a HSBC email; those images could, for example, be pictures of text saying things like “You need to urgently call HSBC on [attacker’s phone number].” This would allow a scammer to hijack a legitimate HSBC email by injecting their own content into the bottom of it. Seriously, HSBC, you ought to fix this.

🕵️♀️ My RSS feed doesn't track you. Dan Q - 1, HSBC - nil,I guess. 😅

When people talk glowingly about the heyday of social media being good, what they’re really talking about is riffing. Before Donald Trump became the president and screwed up all posting that isn’t about him, people would iterate on the most absurd joke possible. For the last few days, a handful of people have been riffing on the idea of YouTube thumbnails but from the point of view of babies, and it’s mostly been good. For posterity, it is worth remembering this riff.

The bit is a riff on something we have all seen a million times: horribly condescending YouTube thumbnails with bait text. The original post comes from an artist called

Jamie. The first meme, “why I’m switching..…” shows a contemplative baby examining a bead maze next to a “greater than” sign and some toy blocks. From there, the rest was history.

“At the end of the day it’s been fun to see people enjoying it, especially in a time where [every] headline online has been miserable,” Jamie told me. “If this silly thing was able to brighten people’s day at all then I’m happy. I’m glad my mutuals seem to be having a laugh instead of being annoyed, haha.”

Here are some of the best YouTube bait thumbnails but they got babies in ‘em. Enjoy.

Also worth mentioning, they've moved on to animals now.

The Five Levels: from Spicy Autocomplete to the Dark Factory

Dan Shapiro proposes a five level model of AI-assisted programming, inspired by the five (or rather six, it's zero-indexed) levels of driving automation.- Spicy autocomplete, aka original GitHub Copilot or copying and pasting snippets from ChatGPT.

- The coding intern, writing unimportant snippets and boilerplate with full human review.

- The junior developer, pair programming with the model but still reviewing every line.

- The developer. Most code is generated by AI, and you take on the role of full-time code reviewer.

- The engineering team. You're more of an engineering manager or product/program/project manager. You collaborate on specs and plans, the agents do the work.

- The dark software factory, like a factory run by robots where the lights are out because robots don't need to see.

Dan says about that last category:

At level 5, it's not really a car any more. You're not really running anybody else's software any more. And your software process isn't really a software process any more. It's a black box that turns specs into software.

Why Dark? Maybe you've heard of the Fanuc Dark Factory, the robot factory staffed by robots. It's dark, because it's a place where humans are neither needed nor welcome.

I know a handful of people who are doing this. They're small teams, less than five people. And what they're doing is nearly unbelievable -- and it will likely be our future.

I've talked to one team that's doing the pattern hinted at here. It was fascinating. The key characteristics:

- Nobody reviews AI-produced code, ever. They don't even look at it.

- The goal of the system is to prove that the system works. A huge amount of the coding agent work goes into testing and tooling and simulating related systems and running demos.

- The role of the humans is to design that system - to find new patterns that can help the agents work more effectively and demonstrate that the software they are building is robust and effective.

It was a tiny team and they stuff they had built in just a few months looked very convincing to me. Some of them had 20+ years of experience as software developers working on systems with high reliability requirements, so they were not approaching this from a naive perspective.

I'm hoping they come out of stealth soon because I can't really share more details than this.

Tags: ai, generative-ai, llms, ai-assisted-programming, coding-agents

I am both a gullible person and a literal one, which means I am frequently disappointed by the realities of figurative language—“pea soup fog,” “hogwash.” When I was a child, one phrase disappointed me more than any other: “pizza ranch.”

In my home state of Iowa, Pizza Ranch was neither a condiment nor a grange for Italian cowboys but instead a disappointing chain of pizza buffets. The chain now has more than 200 locations in 15 states, but if you’ve been to one Pizza Ranch, you’ve been to them all. They all have the same mural of a Conestoga wagon and a fretful-looking horse. Their buffets offer the same dewy, heavily cheesed pizzas nestled under heat lamps in an okay corral. They serve a streusel dessert pizza inexplicably called “Cactus Bread” and have a very affordable party room. I know this because my family gathered in the party room of a Waverly, Iowa, Pizza Ranch after my beloved granny’s funeral—fitting, as she would never have been caught there alive.

But I do not want to dwell on Pizza Ranch as a business. Many talented political journalists have already chronicled its weekly blog of Bible verses, its importance as a campaign stop for Republican politicians, and its co-founder’s arrest for trying to collect semen samples from teenage employees for a fake research study.

I am more interested in its semantic deficiencies. The ultimate betrayal of the Pizza Ranch is that it serves neither ranch-flavored pizza nor pizza-flavored ranch.

Like a lot of Midwesterners, I grew up dipping my pizza in bottled ranch dressing. Before you speed off on your Vespa in a fit of pique, silk scarves snapping menacingly in the breeze, consider the pizza in question. The “default” pie in my hometown was much thicker, softer, and less wholesome than its Neopolitan ancestor. A doughy slice of Casey’s pepperoni could be transported by a tangy splort of ranch. The dressing’s acidity seemed to cancel out the grease, the buttermilk and cheese balancing like a math equation. Central Time pizzaiolos have mostly embraced the combo. Today, many of the region’s higher-end pizzerias make and sell their own ranch for dipping.

To be clear, many people outside of the Midwest also enjoy ranch dressing on pizza. I’m not trying to be one of those people who region-locks basic human experiences, like owning a lawn goose or experiencing weather. But in other regions, the pairing seems more controversial. It has enough national fans that Bath & Body Works made a pizza and ranch candle last year and enough national haters that they almost immediately stopped making it. (If anyone tracks down that candle, I will send you my mailing address with such speed, there will be no time for me to check CaseNet to see if you are a murderer).

I will let the haters adjudicate whether ranch dressing on pizza is “allowed.” This is a question on par with “Is a hot dog a sandwich?” in that it was designed to be answered at excruciating cocktail parties attended by the most boring people you know. My view on this is known. I have done far worse things to ranch dressing for this newsletter.

It was time to do something good to it. For too long, pizza-on-ranch lovers have struggled like goons in an infomercial, fumbling their slices and sauce ramekins with oafish hands. It was time to fuse the flavors. It was time to make the pizza ranch.

My first few batches were needlessly fussy. I tried augmenting a buttermilk base with fresh Italian herbs and homemade tomato powder, or the brine from some lacto-fermented tomatoes I had vac-sealed and then forgotten about for a few months. In recipe development, we call this “the Coward’s Gambit”; the goal is to appease food snobs by reminding them you own The Noma Guide to Fermentation.

But this is not a recipe for the snobs. My ultimate goal was a dressing that tasted not like funky chef bait but like a ‘90s scratch-and-sniff pizza sticker. For that reason, the final dressing augments a classic buttermilk-and-mayo base with mostly dried herbs, powdered alliums, a little fresh parm, and both tomato paste and tomato sauce. The paste and sauce combo was crucial to unlocking the requisite pizza-sticker must.

Yes, that combo also means that I’m going to make you open two different cans and only use parts of them. This is the kind of thing that drives my husband, a more practical recipe developer and benevolent soul, completely crazy. He would go out of his way to scale or adjust the recipe so that you wouldn’t have to put two unfinished cans in the fridge.

But I am a hostile recipe developer who believes in struggling against her readers like Jacob wrestling God.

The end result is worth it—pizza- and ranch-essenced, a multi-dimensional meal rendered on a single plane. It’s a Willy Wonka invention without the sinister finger-wagging. We are all gluttonous children, sprinting toward whatever wild and wonderful things this violent world still holds.

Thank you for supporting Haterade! All proceeds from Haterade subscriptions this month are being donated to the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota, which provides free immigration legal representation to low-income immigrants and refugees in Minnesota and North Dakota. Email me at lizcook.kc@gmail.com if you’d like to receive the receipt at the end of the week. You can make your own donation here.

Recently my wife and I needed to call a car, so out came the apps to compare rideshare prices. There’s always a bit of variation here, but this time was striking.

My wife’s Uber app quoted her $28, while mine gave me $47. Same app, time, and place - but two wildly-different prices.

Who knows why? I’m usually more willing to spend than she is, and I bet that's represented on my user profile. I was paying with a gift card, which surely contributes. Maybe it was a price scraping update, comparison shopping detection, or a system that explores “face-in-the-door” high prices before backing down. From the outside, no one really knows.

That makes me worry. When prices are based on behavior, they incentivize us to behave performatively - after all, the squeaky wheel gets the grease.

Paying different prices is nothing new

Price discrimination has existed for approximately forever - like senior discounts, or coupon books. A business can make a little more money by selectively lowering prices for people who can jump through certain hoops (and might not buy without the discount).

In this simplified demand curve, if the price is $9, then the business only earns $45.

By pricing at $10 for most, with a $1 discount for the price-sensitive blue buyer, the business earns $49 instead.

Behavioral discrimination isn’t a new practice either. When your internet service provider tells you they’re raising rates, do you pay up? Or do you call customer service, wait on hold, threaten to cancel, get transferred to “retention”, and learn about some exciting new discounts that you qualify for? Not everyone has the time or patience to run this gauntlet - and that’s exactly why businesses do it.

When you bring price discrimination into the digital world, there’s nothing different in any individual case. But as the apocryphal Stalin quote goes, quantity has a quality all of its own. Technology gives us not only quantity, but ubiquity - every piece of behavioral context can contribute to your prices.

The foundation for pervasive price discrimination is already here

Unlike in meatspace, every digital action can be cheaply recorded and analyzed.

One example is the “abandoned cart” discount, which is so standard that Shopify and Etsy have step-by-step instructions to set it up as a seller. If you add something to your cart but don’t check out, you might get an email reminder later and a little discount to push you over the finish line. With that knowledge, I find myself abandoning carts even when the price was fine before, on the off chance that a discount materializes.

If you ever try to cancel an Amazon Prime membership, they’ll parade you through a dozen webpages and offers to try and keep you around. The last time I canceled a niche SaaS tool, I was surprised to see the same: Another week free? Another month for a dollar? Please don’t go! I didn’t expect this level of sophistication from a small company. Of course, it wasn’t 100% custom - just the work of Churnkey, a “retention automation” company making the classic please-don’t-cancel discount into a standard practice.

We often think about price discrimination as a discount - great when we benefit, no big deal when we have to pay full price. But what about when you get a “special deal” to pay extra?

In December 2025, Groundwork Collective found that Instacart was charging individualized prices. Some people paid 23% more for the exact same item, from the exact same store, at the exact same time.

In Instacart’s response, they said that these pricing experiments were based purely on behavioral data - not on personal or demographic information. Or in other words, they aren’t looking at who you are, “just” what you’re doing.

Andy Warhol once wrote about American culture:

What's great about this country is America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest.

You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you can know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too.

A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.

From The Philosophy of Andy Warhol

Yesterday, we all drank the same Cokes. But today, we scroll hyper-personalized social media feeds, tailored to our so-called revealed preferences. And tomorrow, maybe we’ll pay wildly-different prices for that same can of Coke (and not because you’re Liz Taylor, but because you spend like she does). It’s one more change that fragments our common experiences into isolated silos.

Personal pricing leads to ritualized posturing

Economically, is this an issue? I don’t really know; if Lucille Bluth is willing to pay $10 for a banana, maybe we should let her - and the shop and platform can split the profits from whatever pricing scheme can make that happen. It’s the invisible hand at work.

It still gives me the ick. It makes me feel like the business is trying to shrink my “consumer surplus” until I pay a perfect, maximized-for-me price. It makes me feel like an adversary, not a customer, and it makes me feel like I should be a worse person to get a better price.

Is it just a cultural difference? As a kid visiting China, I once bought a Gameboy game from a nice lady at the electronics bazaar, a great deal at under $10, or so I thought. Later, I got scolded because I didn’t try to haggle: Remember, the first price they offer is just a starting point to negotiate.

I think this new price discrimination - of abandoned carts, the cancellation song-and-dance, and customers segmented down to individuals - is different. The social expectations are flipped: I don’t think the average person knows that haggling is even an option, nor what factors contribute to personalized pricing.

Only a dummy like me goes to the bazaar without haggling. But today, you probably don’t try to abandon every cart, or switch apps in a way that’s easily-identifiable as comparison shopping, or only buy things that indicate you’re a regular person instead of a fancy rich person. You might let mistakes slide instead of filing a complaint or blasting a company in a Yelp review. All of those events (and who knows which exactly?) are potentially recorded and fed back into your personalized price.

In the future, it’ll be a quiet trick to cultivate your digital reputation of being picky, so you can get the lowest prices and the best treatment. You might even resell that access to someone who wasn’t so careful; or equally likely, spiral into superstitious practice since opaque pricing means you never really know what happened.

On the flip side, we might see the “most favored customer” clause make its way from B2B to consumer contexts - an explicit admission that “the customer is king” is dead. It’ll be an arms race, with data-crunchers looking for opportunities to raise prices while we posture about where we really draw the line.

—

I recently got a kick out of the whimsical CAPTCHA Welcome Mat, a site where you have to prove your humanity before you’re allowed to buy the product. In the bonus round, you get to haggle with a chatbot to earn a coupon for 10% off.

I enjoyed playing that game… once. But I would prefer to be sincere rather than performative, and I don’t love that sincerity is becoming the more expensive option.